Weapons grade plutonium: What is it and what dangers does it pose?

Opinions differ on whether the half ton of weapons-grade plutonium secretly shipped by the U.S. government to the Nevada National Security Site could impact residents’ health and the environment. Regardless, state officials want it gone. Here are some questions and answers about the bomb-making material and the risk it could pose to Southern Nevadans.

What is plutonium?

Plutonium is a manmade, radioactive chemical element with a 24,110-year half-life created in 1940 for use in nuclear weapons.

“Plutonium is one of the most dangerous materials humankind has ever produced,” said Edwin Lyman, acting director of the Nuclear Safety Project at the Union of Concerned Scientists in Washington, D.C., because of its destructive power in weapons and its radioactivity.

There are different types. Plutonium-239 is primarily used for weapon production, while another isotope, Plutonium-240, isn’t particularly useful in the creation of nuclear weapons, according to Steve Nesbit, a member of the American Nuclear Society’s public policy committee who has worked on plutonium transportation projects with the U.S. Department of Energy.

Why is plutonium in Nevada?

The National Nuclear Security Administration revealed in a court filing Wednesday that it secretly shipped half a ton of plutonium from South Carolina to Nevada before the state went to court to try to stop the shipment.

A federal district court ordered the Department of Energy in May to move the material out of South Carolina’s Savannah River Site in South Carolina. The DOE said it selected Nevada for its capability to store large quantities of the metal.

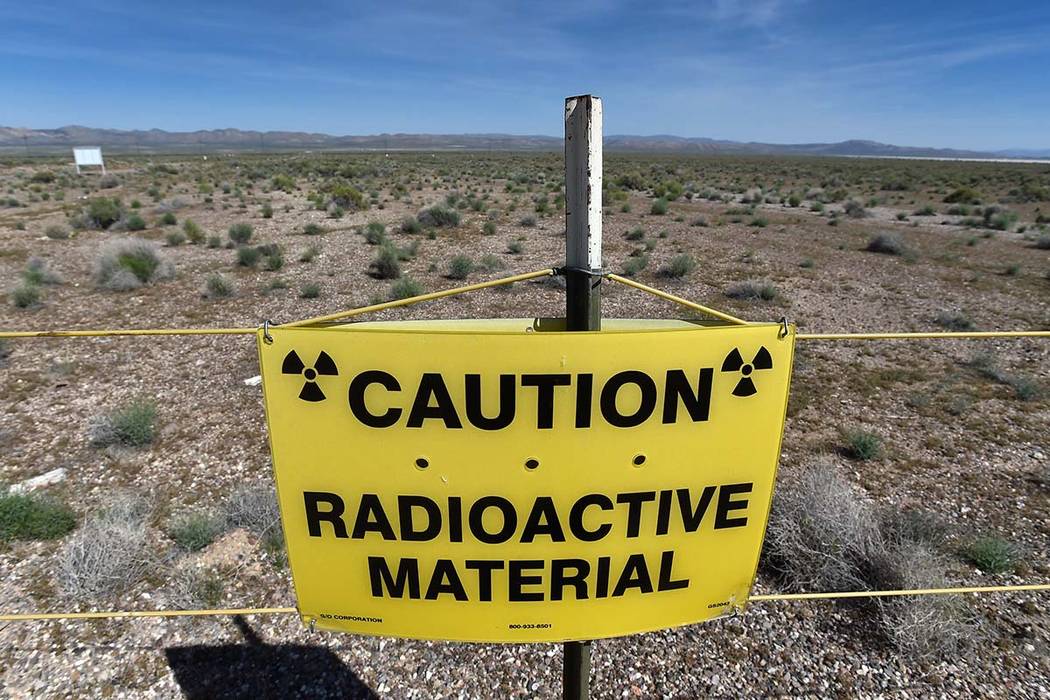

It traveled by truck on a classified route to the Nevada National Security Site, 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas. It will be temporarily stored there until it’s sent to the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico to make warheads for missiles.

Was the shipping risky?

The NNSA said in its filing Wednesday the shipment traveled by secured truck. According to Nesbit, there are few safety concerns. Even in the event of an accident, the shipping containers are built to withstand 30-foot falls, and 30-minute fire and water submersion.

“It’s very well protected and very well contained,” he said.

Nesbit said the containers, made of stainless steel, are typically the size of a large thermos and are sealed and bolted shut to keep material from leaking.

How is it being stored?

The containers are stored within the site’s Device Assembly Facility, said Darwin Morgan, DOE’s spokesman at the security site. He declined to say how many are there, but said they range up to the size of a 55-gallon drum with thick walls.

The cans are stored inside a locked room within the facility, which is guarded and secured with a perimeter fence, Morgan said. Access is limited only to “those people that would need access” and each person entering and leaving the room — and the plutonium — is logged.

How can it affect the human body?

Plutonium is carcinogenic if inhaled or ingested, Lyman said. It only takes a fraction of a gram for the material to settle in a person’s lungs and cause radioactivity that leads to cancer.

It can remain in the body for more than 50 years.

Does it impact the environment?

If plutonium leaks from its container, it can travel by air as particles or in water sources. The Nevada attorney general’s office said in its lawsuit it was concerned about the risk of the radioactive material entering into water sources.

The lawsuit also pointed to two fires tied to Plutonium-239 at the Rocky Flats Plant in Colorado, which sent the material into the environment.

Cleanup is difficult and costly, Lyman said.

What is the risk?

That depends who you ask.

Lyman’s position with the Union of Concerned Scientists is that the transportation of plutonium from South Carolina to Nevada posed an unwarranted risk to those living near the transportation route.

But Nesbit said he had no concerns, given the level of testing of the shipment containers.

“I understand why people are concerned, because given our culture, many people have been indoctrinated to think anything that’s radioactive is hazardous,” Nesbit said. “However, knowing what I know about the cautions that are in place and the sterling safety records associated with it, I think some of the concerns that have been expressed about the shipment are probably overblown.”

Contact Jessie Bekker at jbekker@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4563. Follow @jessiebekks on Twitter.