Transparency is lacking in Nevada government

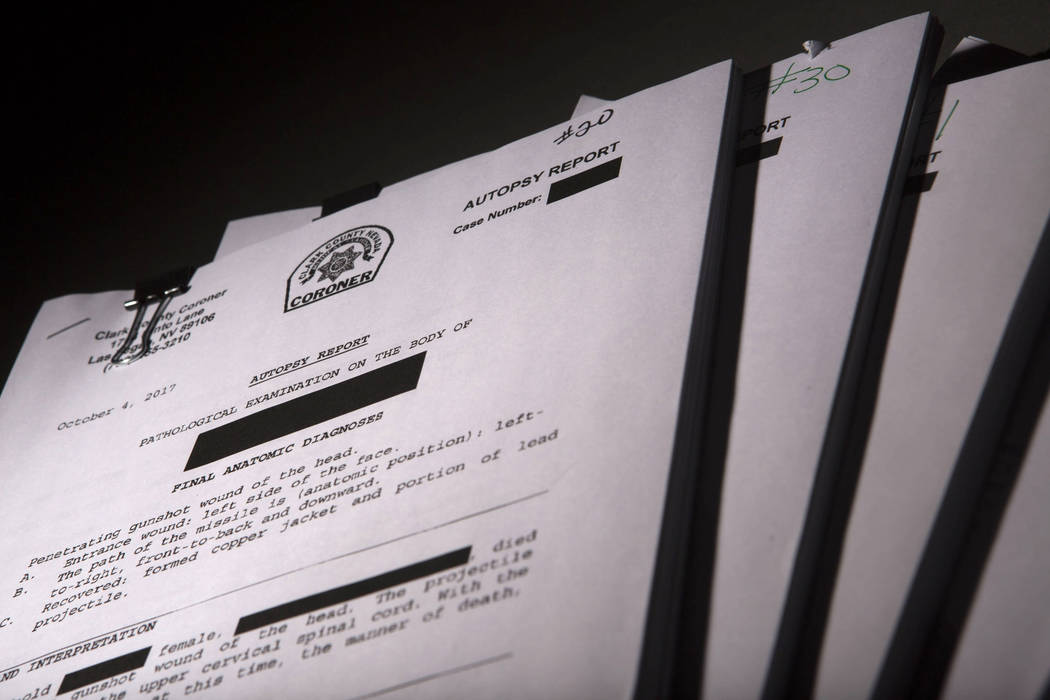

Former state Sen. Mark Manendo sexually harassed more than a dozen women over his years in the Nevada Legislature, leading to his resignation. The transgressions were documented in a $67,000 taxpayer-funded investigation, but the public can’t see the report.

Former Henderson Police Chief Patrick Moers retired with full severance benefits after a law firm hired by the city found he repeatedly sexually harassed at least one employee. The city has declared that report, paid for by city taxpayers, confidential and unavailable for public scrutiny.

UNLV suspended a maternal HIV program without warning, in part because of questions about the misuse of federal grant money. The clinic was audited, but that taxpayer-funded report has been kept secret.

Time and time again the Las Vegas Review-Journal has sought public records, asked questions and demanded openness from local and state government workers whose salaries are paid with taxpayer dollars.

Most requests are honored. However, many are ignored, denied or met with great resistance — especially if the documents would embarrass a public agency and its employees or expose wrongdoing.

“Transparency is a fundamental democratic value,” says John Wonderlich, executive director of the Sunlight Foundation, an open-government advocacy organization. “Ethics abuses and abuses of power thrive in secrecy and have a hard time existing when the public is well-informed.”

Today begins Sunshine Week, a national initiative to promote the importance of open government and freedom of information. The Review-Journal will publish several stories this week about the importance of government transparency.

Rick Edmonds, a faculty member at the Poynter Institute for Media Studies, a nonprofit school for journalism in Florida, said public access to such records are essential to fact-check government claims.

“At the most basic levels it provides insight to what government is actually doing, as opposed to an abridged spin,” he said.

Legal loopholes

The Nevada Public Records Act mandates that all government records, unless specifically declared confidential under state law, shall be made available to its citizenry. Exceptions include some records pertaining to child welfare services and police officers’ home addresses.

In Nevada, however, governments have several avenues to subvert scrutiny.

Officials sometimes refuse to provide records by cobbling together dubious exemptions, decades-old attorney general opinions and unrelated legal clauses.

For records that must be released, turnaround times can stretch into months, and research fees totaling thousands of dollars can amount to an unofficial denial.

And when all else fails, government officials lobby the state Legislature to create or amend laws that will turn public records into confidential ones.

Citizens are not without recourse. When confronted with roadblocks, they can ask the courts to tear them down. That route, however, can turn expensive in a hurry.

“We could file one of these lawsuits everyday,” Review-Journal attorney Maggie McLetchie said. “But, fundamentally, you shouldn’t have to pay a lawyer to get access to records of taxpayer-funded agencies. The whole point is that the government works for us, the people, and we should be able to evaluate the work of the government.”

Nevada Press Association Executive Director Barry Smith said that in addition to its existing public records manual for state agencies, Nevada could strengthen transparency laws by creating an independent, open-government ombudsman. States including Indiana and Washington already have done so.

“It would help establish a better framework for consistency on how responses happen,” he said. “One thing that other states do better: When they have some kind of enforcement or process that’s an intermediate step other than just going to court.”

Unbalanced test

A common method of blocking access to government records in Nevada is governments’ application of a “balancing test” established by a 1990 state Supreme Court decision.

Donrey of Nevada v. Bradshaw allowed governments to withhold records not deemed confidential if officials decide secrecy is in the best interest of the public.

Henderson invoked the balancing test to deny the Review-Journal’s requests for investigation documents about its former police chief. Similarly, when Las Vegas Fire Department employees were accused of having sex at a city fire station, details of the following investigation and discipline were deemed confidential under the balancing test.

“The city regards transparency as an essential aspect of public service. We take pride in our responsiveness to records requests and our thoroughness in providing complete answers,” city of Las Vegas spokesman David Riggleman wrote in an email. “This said, there are a few portions of our records that the city has always maintained as confidential.”

The Donrey case has been cited by local governments in all manner of denied records requests, including those for public employee personnel information, complaints levied against public employees and documents pertaining to law enforcement and code enforcement investigations.

Wonderlich said such denials can be used to thwart potential harm to the public, but the balancing request is often misconstrued if revealing information might damage a government’s reputation.

“There’s no public record exemption for embarrassment,” he said. “If there is something that really can’t be disclosed, (it) can be redacted and the rest of a report can be disclosed. It’s unfortunate when governments use a broad brush approach to say no part of a document can be public, when the sensitive part may actually be a few words.”

Lawmakers exempt

Problems obtaining public records are not limited to Southern Nevada. In 2015 state lawmakers voted to excuse themselves from public records laws.

Their reasoning: the Nevada Legislature is not a “governmental entity,” meaning its elected officials need not make available documents like emails and calendars.

Mari St. Martin, spokeswoman for Gov. Brian Sandoval, told the Review-Journal on Friday that the governor signed the bill knowing it only codified existing precedent dealing with legislative immunity and privilege.

“If subsequent interpretations of this legislation serve to expand or alter laws on public records exemptions, those interpretations are not consistent with the stated intent of the bill, which is to codify rather than change the law as it already existed when the bill was passed,” St. Martin said.

Later in 2015 the state got an “F” grade for government accountability and transparency in the Center for Public Integrity’s nationwide State Integrity Investigation. Among the 50 states, Nevada ranked 46th.

“Nevada’s ‘anything goes’ mentality extends beyond the glittering lights and dinging slot machines of Sin City,” the investigation noted.

Compare Nevada to Washington state, where Gov. Jay Inslee this month vetoed a bill that would have exempted his state’s lawmakers from their own Public Records Act. The governor nixed the proposed measure after receiving more than more than 4,300 phone calls and more than 8,100 emails, the Seattle Times reported.

“I believe legislators will find they can fulfill their duties while being fully transparent, just like state and local governments all across Washington,” Inslee wrote in a statement.

Silver linings

Information unveiled through record requests can lead to meaningful change.

After the Oct. 1 mass shooting, record requests made by the Review-Journal revealed the Nevada Division of Emergency Management had been lax for years in forcing casinos to comply with a state law that requires resorts to file emergency response plans with the state.

Records obtained from the state agency showed that most casinos on the Strip had not updated their plans since 2012 and more than two dozen large Las Vegas casinos had not filed revised plans since 2008.

In response to the Review-Journal’s reporting, division chief Caleb Cage created a public task force to improve oversight of the emergency response plans.

“What Review-Journal readers see on our website and app and in our newspaper never properly reflects the work of our staff,” Managing Editor Glenn Cook said. “For every few reports that are published, there’s another story in limbo, incomplete because a government entity isn’t following the clear language of the Nevada Public Records Act. In some cases, our requests for information are denied solely to protect elected officials from criticism.

“Sunshine Week is the perfect time to educate our audience about all the important questions we’re asking and, in some cases, the lawsuits we’re filing to find out how taxpayer dollars are being spent.”

Contact Michael Scott Davidson at sdavidson@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3861. Follow @davidsonlvrj on Twitter.