Marsy’s Law could hinder transparency for Nevada public records

Law enforcement agencies in South Dakota now wait 72 hours before revealing the names of victims involved in car crashes or crimes.

In one instance, law enforcement kept confidential the name of a business that was broken into.

This month, a police officer who shot a man invoked Marsy’s Law to keep his name secret.

These are examples of the unintended consequences of Marsy’s Law — a constitutional amendment that has been on the books in South Dakota for two years and is Question 1 on the Nov. 6 ballot in Nevada.

“From the standpoint of the public’s right to know and keeping the public informed in a timely manner, Marsy’s Law has been a real headache in South Dakota, particularly for journalists,” said Dave Bordewyk, executive director of the South Dakota Newspaper Association.

Question 1 outlines 16 rights for crime victims, including privacy, protection from the defendant, notice of all public hearings, full and timely restitution and refusal of interview or deposition requests without a court order.

It also broadens the definition of victim to any person directly or “proximately” harmed by the commission of a criminal offense.

Complex law

In the time leading up to the passage of Marsy’s Law in South Dakota, Bordewyk remembers significant support and money for the constitutional amendment, and a lack of organized opposition.

There was also a lack of understanding regarding the ballot measure, even from those who worked in the news media, he said.

A similar situation is playing out in Nevada.

While the American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada and the Nevada Association of Criminal Justice Attorneys oppose Question 1, the two groups can’t compete with the money being spent in support of the measure, which was crafted by California billionaire Henry T. Nicholas, co-founder of the semiconductor company Broadcom.

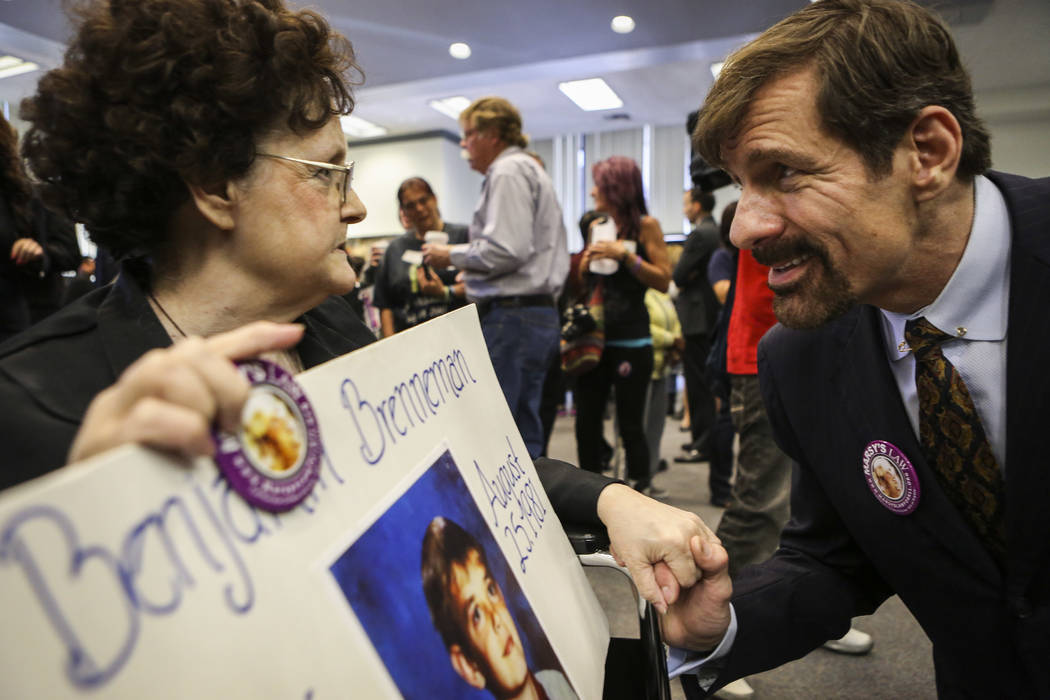

The effort started after his sister, Marsalee “Marsy” Nicholas, was killed by her ex-boyfriend in 1983. He then confronted her family, who had no idea he was out of jail.

“It’s hard to fight the millions of dollars spent scaremongering people about this issue,” said Tod Story, executive director of the ACLU of Nevada. “Nevadans should know we already have victims’ rights on the books in Nevada as a law. This takes it a step further, but what we have currently works just fine.”

Maggie McLetchie, a First Amendment attorney who represents the Las Vegas Review-Journal, said changing the law through the state constitution is complex and would take years to fix.

“I don’t think most people will have the opportunity to read the entire thing and really understand what it means,” she said. “It’s the kind of language that looks good on paper, but A, isn’t really necessary, and B, has unintended consequences.”

Effects on disclosure

McLetchie, who has sued government agencies in Nevada for access to public records, believes those same agencies will exploit Marsy’s Law to shield themselves from additional scrutiny.

“Even though the Public Records Act is really strong on its face and it’s supposed to be interpreted in favor of disclosure, government agencies grab hooks on anything they can to fight disclosure,” McLetchie said.

In one recent case, she had to litigate against the district attorney’s office for access to information about paying witnesses in exchange for their testimony.

Marsy’s Law has been endorsed by Clark County District Attorney Steve Wolfson, Clark County Sheriff Joe Lombardo, Gov. Brian Sandoval and Sens. Dean Heller and Catherine Cortez Masto, among others.

“The district attorney doesn’t just work for the victims,” McLetchie said. “The district attorney works to bring justice. We have a right to know how the district attorney is prosecuting cases.”

With Marsy’s Law, McLetchie is particularly concerned with one section that calls for victims “to be treated with fairness and respect for his or her privacy and dignity, and to be free from intimidation, harassment, and abuse, throughout the criminal or juvenile justice process.”

She said the “vague and broad language” is ripe for exploitation by the government to thwart disclosure and could lead to the closing of court proceedings and records once a matter is in court.

The broadened definition of “victim” is also a concern, she said, and it led to a South Dakota Highway Patrol trooper exploiting that provision.

South Dakota Attorney General Marty Jackley said the officer was attacked by the man before shooting him, which made the trooper a victim, according to the Rapid City Journal.

McLetchie believes if information like this is kept out of the public view, it will erode trust in law enforcement.

“There are more questions with the incident involving the trooper in that case because the information isn’t public,” she said.

Las Vegas police officers have been involved in 20 shootings this year, 10 of them fatal.

“I think transparency about law enforcement and the use of violence is important,” McLetchie said. “Law enforcement can’t just use force willy-nilly and avoid transparency and accountability from the public. Where there is transparency and the public can see what happened — when they can see they haven’t done anything wrong — it increases our trust and faith in law enforcement.”

‘Heavily vetted’

For opponents to concentrate on South Dakota, where the law has been narrowly interpreted, is “really disingenuous,” said Will Batista, Marsy’s Law for Nevada state director.

“Since then we’ve been able to work with the stakeholders in the state to clarify what those privacy aspects are,” Batista said. “It relates or applies to the personal identifying information — a victim’s name, date of birth, residence.”

Batista say his organization feels very strongly that a victim’s privacy must be respected, as victims of crime are prone to re-victimization.

Additionally, he said that the constitutional amendment, which had to pass two different state legislative sessions, has been “heavily vetted,” pointing to the support of Sandoval and Cortez Masto.

“We have worked with the key stakeholders who will be responsible for the implementation process,” Batista said. “We don’t feel like it will be a concern in Nevada.”

In California, where Marsy’s Law passed in 2008, Nikki Moore, legal counsel for the California News Publishers Association, said there’s no case law that has interpreted the constitutional amendment to limit the public’s right of access.

“It hasn’t been as much of a thorn in our side because we already have a bad law in regard to police records,” Moore said, adding that she hasn’t seen any member of the CNPA challenge Marsy’s Law with a lawsuit.

Story said a lawsuit would be the only way in the near term to make changes if the law were passed, or the constitution would have to be reopened again — eight years down the road.

In June, South Dakota was the first state to approve changes to the law, adding an amendment that requires victims to opt in to many of their rights and specifically lets authorities share information with the public to assist in solving crimes, according to The Associated Press. However, Bordewyk said the changes have not sped up the release of victim information from law enforcement agencies.

In a particularly egregious example, a daily newspaper in South Dakota last year ran an obituary of a person killed in a car accident, while the front-page story about the accident didn’t include the names of the people involved.

“I remember when HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) came along and the mess that that created in terms of news gathering,” Bordewyk said. “It created massive confusion about what can and cannot be released. This is the HIPAA of the law enforcement community.”

More broadly, the measure is unnecessary, McLetchie said, “because law enforcement, including district attorneys, shouldn’t need a constitutional amendment to make them do what they should already be doing — working with victims.”

Story agreed.

“Other states have had numerous problems and have had to spend millions of dollars to implement these new requirements of Marsy’s Law, which has bogged down the justice system,” Story said. “We will save ourselves a lot of heartache and trouble by not passing Marsy’s Law and continuing to enforce the laws we have already on the books.”

Follow @NatalieBruzda on Twitter.