Legislators push Stolen Valor bills

What’s the difference between a white lie and fraud?

The Stolen Valor Act of Nevada, as proposed by companion bills in the Legislature, hopes to answer that.

The twin bills aim to help prosecute military impostors and close a loophole in the federal Stolen Valor Act.

“Stolen valor” is the term used to describe phonies who lie about their military decorations and service records, dishonoring military courage. It was made a federal crime in 2005. But a federal court recently ruled that the law violates the First Amendment protecting free speech, even the freedom to lie.

The Nevada bills — Senate Bill 356, sponsored by state Sen. Elizabeth Halseth, R-Las Vegas, and Assembly Bill 379, sponsored by Assemblyman Scott Hammond, R-Las Vegas — begin with the caveat that the federal judges found the current federal law restricts free speech rights but could be modified into an anti-fraud statute.

“The intent of this bill is to honor those who have served, by making it more difficult for those who pose as our armed services personnel,” Hammond said. “Whether it was to receive monetary benefits, false admiration, help secure improved employment or community status, this bill might force those who masquerade as a veteran to think twice by making the penalties for doing so more harsh.”

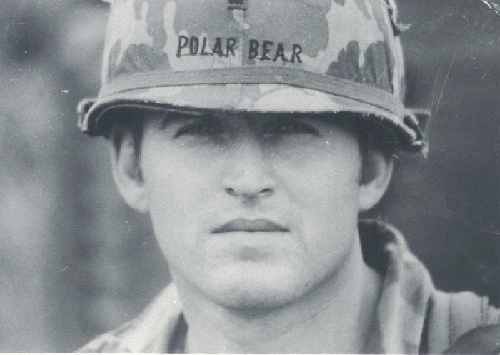

Hammond said he was inspired by retired Lt. Col. Bill Anton, a Vietnam War veteran and an Army Ranger Hall of Famer from North Las Vegas, who provided language for the Nevada measures. Anton also persuaded the Nevada Veterans Services Commission to support the bills.

“These citizens feel their service to country has been cheapened, demeaned, or otherwise disgraced by those who impersonate them,” Hammond said.

Anton said there is no difference between a white lie and fraud. But if the courts insist on basing stolen valor on the legal definition of fraud, then so be it.

“Fraud is making out something that is totally untrue,” Anton said Tuesday. “A white lie could be like when your wife asks, ‘How do you like my dress?’ And, you say, ‘That’s great.’ While that might be a white lie, it might save your marriage.”

WHEN LYING BECOMES FRAUD

The Nevada bills spell out the difference: Fraud means “intent to gain something of any value. That could be free admission, a lunch, and it doesn’t have to have a value of $70,000 or $100,000,” Anton said.

In the past, the U.S. attorney’s office has declined to pursue some stolen valor cases, saying the monetary values involved were too small compared to the time prosecutors would have to spend on them, he said.

So, the Nevada bills target phonies who lie and make false representations about military service, medals and awards with the “intent to obtain some benefit or something of value,” or to mislead or defraud another person. But they don’t put a price tag on “something of value.”

The bills assign penalties for various violations. It is a misdemeanor if false military representation is used to obtain employment, or get elected or appointed to public office. It’s a gross misdemeanor if someone forges military documents, service records and/or falsely wears top valor medals. It’s a felony to forge or falsely wear the Medal of Honor, which carries a fine of up to $100,000 and a minimum of one year in prison or probation.

Nevada Chief Deputy Legislative Counsel Brad Wilkinson said the Stolen Valor bills take aim at people who fake or exaggerate military service or claim medals and awards they never earned for purposes of gaining money or benefits at another person’s expense.

“You’re not just making false representation to receive personal glory or accolades or being well regarded in the community to feel better about yourself,” he said. “You’re doing it to obtain actual tangible benefit.”

Allen Lichtenstein, general counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada, said the bills’ language is “fairly nebulous” and lacks definition.

“The real question is what is something of value and how much value?” he asked. “I think the intent was to make it an anti-fraud thing. Since fraud is already illegal is this superfluous?”

Given that Nevada and several other states are trying to adopt or have adopted their own Stolen Valor laws, Lichtenstein said he wonders if states have jurisdiction over what appears to be a federal issue on military service.

“It’s a little bit like the Arizona immigration law,” he said.

NEVADA’S TEST CASE

In December, a U.S. District Court judge sentenced Air Force veteran and former Veterans Affairs clerk David M. Perelman to a year in prison for fraudulently obtaining a Purple Heart medal, which he used to steal $180,000 in disability benefits. He pleaded guilty in August to theft of government funds, a felony, and unlawful wearing of a service medal, a misdemeanor. It was the first known prosecution in Nevada under the federal Stolen Valor Act.

U.S. attorneys had accused Perelman, of Las Vegas, of wearing a Purple Heart in 2008 during a national convention of recipients of the medal. He was the Nevada commander of the Military Order of the Purple Heart that year and had worked at a local VA office. He claimed he was wounded in combat in Vietnam when in fact he was wounded by a self-inflicted gunshot in 1991, according to an indictment.

During sentencing, U.S. District Judge Kent Dawson allowed Perelman to retain his right to appeal the constitutionality of the Stolen Valor Act of 2005 even though he ruled the circumstances in his case differed from free-speech rights that were at issue in the case of Xavier Alvarez, whose stolen valor conviction was overturned by the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Dawson found in Perelman’s case that the issue transcends free speech, because Perelman’s lies allowed him to profit through phony documents he used to obtain a Purple Heart in 1994.

Perelman’s attorney filed an appeal with the 9th Circuit, and last week the ACLU filed friend-of-the-court papers seeking to dismiss the Stolen Valor Act count, similar to the Alvarez case.

Lichtenstein said the ACLU’s position is if the law about making false representations of having been awarded a valor medal — or the Medal of Honor, in Alvarez’s case — is unconstitutional because of free speech, then the section of the law that pertains to wearing a medal, such as a Purple Heart, in Perelman’s case is also unconstitutional.

He cited other examples of free-speech issues involving military items, including those used for anti-war protests, theatrical productions and movies, such as “Forrest Gump,” loosely based on Vietnam War Medal of Honor recipient Sammy Davis.

But neither Alvarez nor Perelman — who also once claimed to be a Medal of Honor recipient — were protesters or actors. Perelman was investigated in 1997 for that claim made in a phony Medal of Honor citation that read like one for World War II hero Audie Murphy, but the case was dismissed because of a delay in prosecution.

CONSUMER PROTECTION

Retired Army Maj. Gen. Scott Smith is a highly decorated Vietnam War combat veteran, U.S. Military Academy West Point graduate, a former member of the Nevada Veterans Services Commission and currently the executive director of the UNLV Institute for Security Studies. He believes that “no soldier wants to step on anyone’s First Amendment rights.”

“I believe in the old saw, ‘I disagree with you, sir, but have shed blood to defend your right to your view.’ ”

But, Scott said, “There is a point at which freedom of speech can become using language to gain a benefit that one is not otherwise entitled to. Whether that benefit is money, a job, or a vote, if it has value then a transgressor has obtained something of value in exchange for nothing of value.”

That is why he supports a Nevada Stolen Valor Act even if it boils down to being an enhanced, anti-fraud statute.

“I believe the public should be protected from people who would defraud them, and that’s my understanding of what AB379 and SB356 do,” Scott wrote in an email. “In a sense, it’s almost immaterial that we’re talking about military courage. In a way, this is a consumer protection matter, albeit with a narrow focus.”

Anton, the decorated Army Ranger who is president of Special Forces Association Chapter 51, said he hopes Congress will follow suit in amending the 2005 Stolen Valor Act if the 9th Circuit decision in California’s Alvarez case is appealed but not overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court. Like the proposed Nevada law, the federal law should make specific reference to violations for falsely claiming “to be or to have been a member of any elite United States Special Operations Command.”

There should be no mercy for lying about being a military hero, or for that matter, a member of the Army Special Forces, Rangers, Navy SEALs or Marine Corps Force Reconnaissance and other units that support special operations, Anton said. That’s because it devalues heroism and all those who really served in those units, and those who served honorably in all branches of the U.S. armed forces.

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at

krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.