McConnell Rule? Biden Rule? The politics behind this Supreme Court pick

WASHINGTON — As Senate Republicans rush to confirm Judge Amy Coney Barrett, President Donald Trump’s nominee for the U.S. Supreme Court, Democrats, who lack the votes to block the appointment, are crying foul and trying to slow down the process.

Republican senators, who hold a 53-47 majority, immediately united and announced they would seek to confirm the president’s pick following the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, 87, even though the presidential election was less than two months away.

Democrats have protested the decision to move forward quickly.

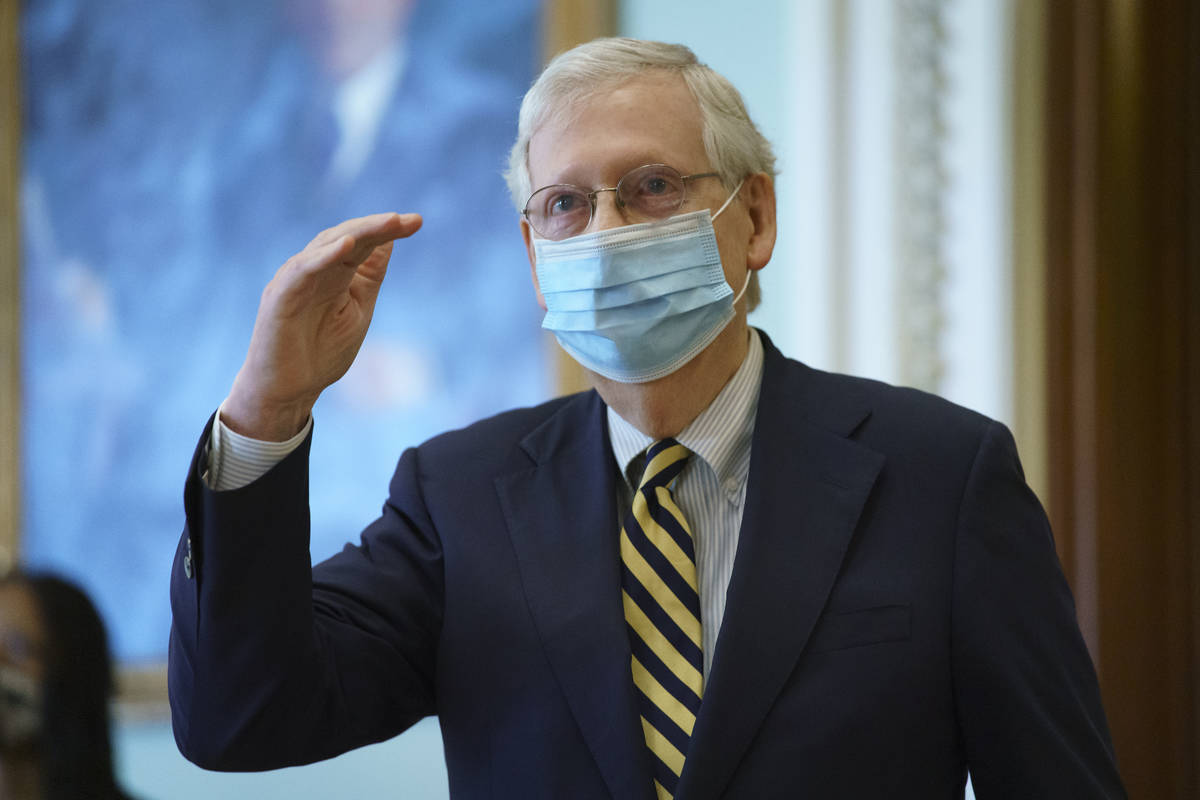

Their opposition centers on their insistence that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., set a precedent four years ago when he and the GOP Senate blocked a vote on Democratic President Barack Obama’s nominee, Judge Merrick Garland, for a presidential election year vacancy created by the death of Justice Antonin Scalia.

The so-called “McConnell Rule” has been cited repeatedly in the past week by Democrats who insist the Senate must wait until after the Nov. 3 election to vote on confirmation — a position backed by two GOP senators, leaving Republicans with a maximum of 51 votes to confirm and little margin for error. If the nomination is delayed and Democrat Joe Biden wins the presidency, it would allow him to nominate a candidate to fill the post instead of Trump.

Sen. Jacky Rosen, D-Nev., in a Senate floor speech, said she had hoped her GOP colleagues would have followed their own “precedent on this process — the McConnell Rule — and ensure that the American people have their say at the ballot box before filling this vacancy.”

Instead, Rosen said, the American people received “political gamesmanship.”

The ‘Biden Rule’

But Republicans have countered with a defense of their actions, both in 2016 and now in 2020, citing a speech in 1992 by then-Sen. Joe Biden, D-Del., the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Biden then warned that if Republican President George H.W. Bush sent up a nominee to fill a vacancy on the high court, the Democratic-controlled Senate should not confirm or fill the seat until after the election. At the time Biden spoke, there was no court vacancy, and his speech centered on a hypothetical opening with a divided government — a Democratic Senate and Republican president.

A year after the speech, President Bill Clinton appointed Ginsburg to replace retiring Justice Byron White, who retired.

Republicans have tabbed that speech as the “Biden Rule,” one that McConnell referred to in 2016 when, with the government divided, he denied a Judiciary Committee hearing and vote on Garland.

Now, with a Republican president and Republicans in the Senate majority, senators argue that it is the constitutional duty of the GOP upper chamber to hold confirmation hearings on a nominee selected by a GOP president.

“The president’s job is to fill a vacancy. The Senate’s job is to fill a vacancy,” said Sen. Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn., who served as education secretary under the elder President Bush.

He said Biden’s reasoning was sound in 1992, when he was speaking about filling a vacancy in a presidential election year after the polarizing confirmation of Justice Clarence Thomas.

“(Biden) gave a very eloquent explanation of why, when you have a divided government, it’s better to let the people decide, so that’s what we did with Merrick Garland, and that’s what’s been done throughout history,” Alexander said.

But before there was a Biden Rule, or McConnell Rule, there was the “Thurmond Rule.”

In 1968, Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-S.C., blocked a Supreme Court chief justice nominee by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Thurmond argued the Senate should not move forward with confirmation hearings after a certain point during a presidential election year because the process would be overtaken by politics, according to the Congressional Research Service, the nonpartisan think tank of the legislative branch.

That “rule” has been discredited as doctrine by legal scholars, but used by McConnell, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., and Sen. Pat Leahy, D-Vt., in past arguments for and against election-year nominations.

McConnell justified his actions in 2016 against Garland citing the “Thurmond-Leahy” rule.

No rules

But there are no “rules,” judicial experts agree, and both parties have engaged in mutually disingenuous arguments over Senate procedures and norms in recent years as the ideological stakes prompt an increase in attempts at partisan obstruction.

Still, some judicial experts accuse the current Senate leader of hypocrisy, something McConnell’s office has strongly rebutted with historical facts on nominations and confirmations.

“McConnell has twisted history to suit himself,” said Carl Tobias, a University of Richmond Law School professor and founding faculty member of the William S. Boyd School of Law at UNLV. “We have this concrete precedent that McConnell made up in 2016, and now he won’t live by it.”

But Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, a former state solicitor general who argued cases before Ginsburg at the Supreme Court, said Republican and Democratic presidents have nominated candidates in an election year 29 times in American history.

Nineteen of those times, the White House and the Senate were controlled by the same party. “When that happened, the Senate took up and confirmed nominees 17 of the 19 times,” Cruz said. When the presidency and the Senate were controlled by different parties, which occurred 10 times, nominees were confirmed only twice. “2016 was one of those examples,” Cruz said.

Indeed, since 2016, McConnell has pointed out in numerous interviews that a divided government, with the Senate and presidency controlled by different parties, hasn’t confirmed a Supreme Court nominee in an election year since 1888.

Political considerations

Regardless of the rationale expressed by senators, Trump cut through the clutter and told reporters that appointing a candidate to the Supreme Court vacancy was based largely on political calculations.

He said a justice is needed on the court because of litigation he expects will be filed in the presidential election, and those cases could end up before the justices on the highest court.

Depending on the circumstances, a Supreme Court decision could determine the presidency for the next four years. The high court settled the contested Florida recount in the 2000 presidential election, sealing the election of Republican George W. Bush.

“I think this will end up in the Supreme Court,” Trump said. “And I think it’s very important that we have nine justices.”

Meanwhile, partisan tempers flared in the Senate this week. It’s not surprising considering the battles waged over past Supreme Court nominees.

Republicans point to Biden and the Democrats who attacked and derailed Robert Bork’s nomination 1987, and the bruising confirmation battle that took place following the nomination of Clarence Thomas in 1991.

Democrats are still seething over McConnell’s refusal to take up Garland’s nomination, but McConnell, Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., and other Republicans say Democrats crossed the line when they excoriated Judge Brett Kavanaugh, accused during his Supreme Court confirmation hearing in 2018 of sexual assaults that allegedly occurred decades earlier.

Legal experts and some lawmakers worry that the hyper-partisan debate over the so-called “McConnell Rule” and “Biden Rule” masks political motives to cover up ideological power grabs that will result in “court-packing.”

Court balance tips

The confirmation of Trump’s nominee will theoretically tip the court to the right with a 6-3 majority of Republican appointees that would include several reliably conservative justices.

Sen. Ed Markey, D-Mass., and others said the rushed GOP process could pave the way for a new Democratic Senate to create new seats on the Supreme Court to be filled by a Democratic president.

Lacking the votes to reject a Republican nominee, Democrats cannot block Trump’s pick without more Republican help. One more GOP defection could create a 50-50 tie that would have to be broken by Vice President Mike Pence. Two more GOP defections would all but end the process.

Democrats, like Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., said they must make their case to the American people to halt the nomination. In many states, though, voting for November’s election has already begun.

Time-consuming process

With the election looming, the Republican Senate is pushing for an expedited process that must include an FBI investigation and background check, vetting by the American Bar Association, Senate interviews and schedule of hearings before the Judiciary Committee. Only when those steps are completed can the floor debate and a final up-or-down vote take place.

McConnell said the current Senate will vote on the nomination. He noted that voters increased the Republican majority in the Senate in the 2018 election, albeit only by two seats. (That same election, considered a referendum on Trump, also resulted in a sweeping Democratic takeover of the House.)

McConnell said voters increased the Senate majority “on our pledge to continue working with President Trump, most especially on his outstanding judicial appointments.”

Contact Gary Martin at gmartin@reviewjournal.com or 202-662-7390. Follow @garymartindc on Twitter.