Gun policy debate blocked by Senate Republicans

WASHINGTON — Democrats’ first attempt at responding to the back-to-back mass shootings in Buffalo and Uvalde, Texas, failed in the Senate Thursday as Republicans blocked a domestic terrorism bill that would have opened debate on difficult questions surrounding hate crimes and gun safety.

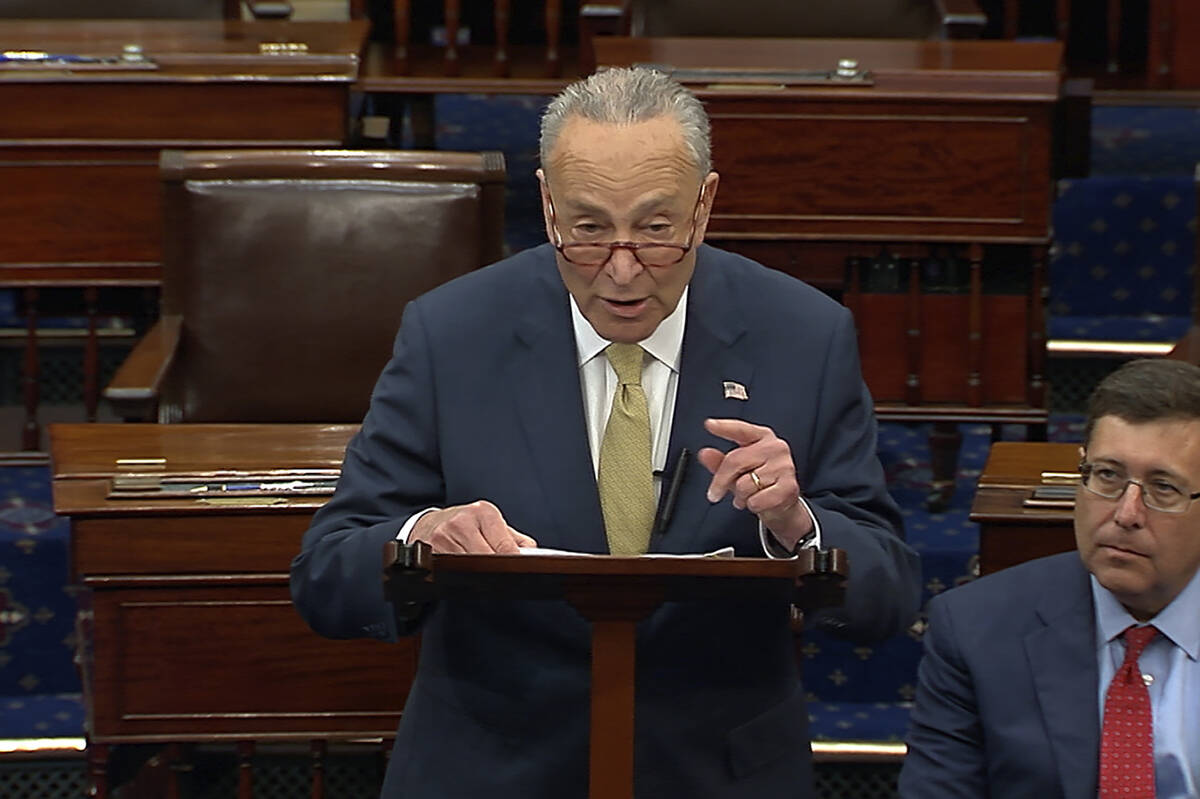

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y. tried to nudge Republicans into taking up a domestic terrorism bill that had cleared the House quickly last week after mass shootings at a grocery store in Buffalo, New York, and a church in Southern California targeting people of color. He said it could become the basis for negotiation.

But the vote failed along party lines, raising fresh doubts about the possibility of robust debate, let alone eventual compromise, on gun safety measures. The final vote was 47-47, short of the 60 needed to take up the bill. All Republicans voted against it.

“None of us are under any illusions this will be easy,” Schumer said ahead of the vote.

Rejection of the bill, just two days after the mass shooting at Texas elementary school that killed 19 children and two teachers, brought into sharp relief Congress’ persistent failure to pass legislation to curb the nation’s epidemic of gun violence.

Schumer said he will give bipartisan negotiations in the Senate about two weeks, while Congress is away for a break, to try to forge a compromise bill that could pass the 50-50 Senate, where 60 votes will be needed to overcome a filibuster.

Group meets again

A small, bipartisan group of senators who have for years sought to negotiate legislation on guns met Thursday afternoon for the second time searching any compromise that could win approved in Congress.

They narrowed to three topics — background checks for guns purchased online or at gun shows, red-flag laws designed to keep guns away from those who could harm themselves or others, and programs to bolster security at schools and other buildings.

“We have a range of options that we’re going to work on,” said Sen. Chris Murphy, D-Conn., who is leading the negotiations. They broke into groups and will report next week.

Murphy has been working to push gun legislation since the 2012 attack at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, that killed 20 children and six educators. He was joined Thursday by Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., Sen. Pat Toomey, R-Pa., and others. Collins, a veteran of bipartisan talks, called the meeting “constructive.”

What is clear, however, is that providing funding for local gun safety efforts may be more politically viable than devising new federal policies.

GOP Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina exited the meeting saying there is no appetite for a federal red flag law or a so-called yellow flag law — which permits temporary firearm confiscation from people in danger of hurting themselves or others, if a medical practitioner signs off.

But Graham said there could be interest in providing money to the states that already have red flag laws or that want to develop them. Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., who circulated a draft at the meeting, will work with Graham on a potential compromise.

“These laws save lives,” Blumenthal said.

Toomey told reporters that Manchin-Toomey background check bill — which failed in the aftermath of the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting a decade ago — still does not have enough support. Manchin said he hoped this time would be different.

“I can’t get my grandchildren out of my mind. It could have been them,” Manchin said.

None of the lawmakers could say definitively if any of the efforts will be able to win all Democrats and have the 10 Republican senators it needs to advance past a GOP-led filibuster.

McConnell, Cornyn speak

Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell, who has said little about gun legislation since the several tragedies have unfolded, told reporters he met with Republican Sen. John Cornyn of Texas earlier and encouraged senators to work together across the aisle on workable outcomes.

“I am hopeful that we could come up with a bipartisan solution that’s directly related to the facts of this awful massacre,” McConnell said.

The domestic terrorism bill that failed Thursday, meanwhile, dates back to 2017, when Rep. Brad Schneider, D-Ill., first proposed it after mass shootings in Las Vegas and Southerland Springs, Texas.

The House passed a similar measure by a voice vote in 2020, only to have it languish in the Senate. Since then, Republicans have turned against the legislation, with only one GOP lawmaker supporting passage in the House last week.

“What had broad bipartisan support two years ago, because of the political climate we find ourselves in … or to be more specific, the political climate Republicans find themselves in, we’re not able to stand up against domestic terrorism,” Schneider, who came into office in the wake of the Sandy Hook school shooting, told The Associated Press.

Republicans say the bill doesn’t place enough emphasis on combating domestic terrorism committed by groups on the far left. Under the bill, agencies would be required to produce a joint report every six months that assesses and quantifies domestic terrorism threats nationally, including threats posed by white supremacists and neo-Nazi groups.

Proponents say the bill will fill the gaps in intelligence-sharing among the Justice Department, Department of Homeland Security and the FBI so that officials can better track and respond to the growing threat of white extremist terrorism.

The efforts would focus on the spread of racist ideology online like replacement theory, which investigators say motivated an 18-year-old white gunman to drive three hours to carry out a racist, livestreamed shooting rampage two weeks ago in a crowded supermarket in Buffalo. Or the animus against Taiwanese parishioners at a church in Laguna Woods, California, that led to the shooting death the following day of one man and the wounding of five others.

While Schneider acknowledged that his legislation may not have stopped those attacks, he said it would ensure that those federal agencies work together to better identify, predict and stop threats.

Under current law, the three federal agencies already work to investigate, prevent and prosecute acts of domestic terrorism. But the bill would require each agency to open offices specifically dedicated to those tasks and create an interagency task force to combat the infiltration of white supremacy in the military.l-shootings