Back to baseball and perhaps UNLV: Commissioners say farewell

Together they have served for nearly 45 years in political office in Southern Nevada, with careers that ran parallel beginning on the Las Vegas City Council in the 1990s and moving to the Clark County Commission the following decade.

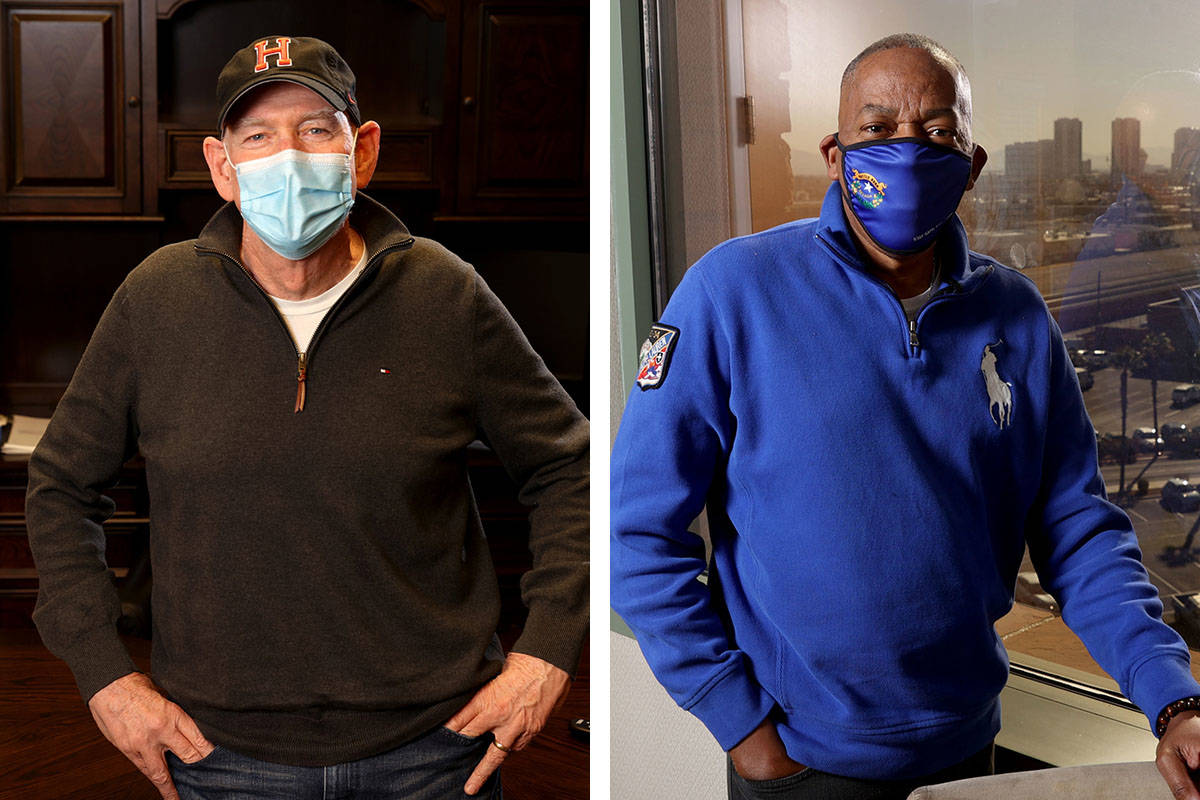

Now, as their successors prepare to be sworn in at the beginning of 2021, Clark County Commissioners Lawrence Weekly and Larry Brown will soon find themselves in an unfamiliar position: out of public life.

The two Democratic lawmakers said in recent, separate interviews that they will officially wrap up their third terms on the commission — the maximum allowed under state law — with no regrets, although Weekly acknowledged feeling torn about leaving.

“Could I have maybe settled for four more years? Yeah, maybe,” he said. “But (I am) at a point where, you know, allow somebody else an opportunity and a chance to serve. So, I’m OK with it as well.”

Well wishes

On Dec. 15, during their last commission meeting, aides were struck by emotion as they spoke about fond memories with the commissioners from behind the scenes.

Brown would engage his staff on current events, classic rock and sports and seemed to have an unending thirst for coffee. Weekly’s greeting of “guess what?” upon entering the office on Mondays signaled that he had been inspired over the weekend by a dream, movie or something else to give back to the community.

“These two gentlemen really helped create the Las Vegas that we know,” Commissioner Tick Segerblom said.

Gov. Steve Sisolak, a former commissioner who served two terms with the lawmakers, called in to the meeting.

“It was some of the best times that I’ve had,” Sisolak said. “You’ll never find more dedicated public servants. They’ve gone above and beyond.”

Plans for 2021

Brown, 63, a former minor league pitcher and pending inductee into the Southern Nevada Sports Hall of Fame, told the Review-Journal that he now expects to work with a charitable foundation for the Las Vegas Aviators to raise money for youth sports.

Weekly, 56, did not divulge specific plans about his future, but he said there are opportunities on the table for him to do “something different.” Brown might have offered a clue, however, saying Weekly was “ultimately going to be teaching at UNLV, hopefully in a professorship.”

“I have never served with or seen a public official so dedicated to his community,” Brown said.

Different paths to dais

Both former councilmen consider each other personal friends and similarly viewed themselves as lawmakers who approached the role as consensus-builders. Each also said they would most miss the regular interactions with constituents, while Brown expressed disappointment that the pandemic had stolen much of that opportunity in his final year.

Despite their commonalities, their entrances into politics were markedly different. Brown, who was high school class president and a college club president and majored in government, said politics was a likely part of his future as the “ultimate extension” of his family-instilled desire to serve people. Weekly did not.

“For me, you know as I tap into my beliefs and my faith, I was destined to do this unbeknownst to myself because I never had it as a part of my forecast,” Weekly said. “So I’m where I’m supposed to be.”

While a management analyst for the city, Weekly was appointed to the newly created Ward 5 seat on the Las Vegas council in 1999. Brown had been elected to the council two years earlier. Weekly was then appointed to the commission in 2007, and Brown was elected a commissioner in 2008.

Champion for the underserved

Weekly, a native Las Vegan who was adopted and is a first-generation college graduate, said he was proud to be a strong advocate for diversity, equity and inclusion.

Politics had helped him mature and understand his value, he explained, as a mentor and supporter of young people, fostered and adopted children, the LGBTQ community, Dreamers and other underserved and marginalized groups.

“Everybody needs to have a voice at the table, and we all need to be sensitive to everyone’s needs and beliefs,” he said.

Under his leadership, two District D gyms flourished, and he frequently sponsored community events. He was also the first African American to chair the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority.

But having been the only person of color on the council and commission, representing the predominantly Black and underserved westside of Las Vegas, Weekly acknowledged that he often felt it was assumed that he would be the voice of the minority.

“I found myself many times expected to be part of it because communities like that … feel like, ‘well your colleagues really don’t have to be involved in that,’ and I always tell people, ‘no, yes, they do,’” he said. “They need to be involved in it more than I do.”

On race and racism

At the height of the civil unrest this summer in Las Vegas over killings of Black people by police across the U.S., Weekly and Brown disagreed over the phrase “Black Lives Matter,” which Brown said had given him an “uneasy feeling” because it was not inclusive of all lives.

“I can’t see through the eyes of what Larry’s seeing, but Lord, I wish he could walk a day in my shoes,” Weekly said at the time, relaying the painful conversations that parents must have with their Black children about what to do when pulled over by police.

From his office at the county Government Center, Brown recently pulled out a years-old T-ball team photograph. He was a coach then, and Shay Mikalonis, the Las Vegas police officer who was shot and paralyzed from the neck down at the end of a Black Lives Matter protest in June, was one of his players.

Brown said he had been concerned that the focus on social injustice was ignoring the first responders who protect the community, adding that while a majority of protesters in the city had demonstrated peacefully, a “significant number” were intent on causing trouble.

“My comments were not against any kind of social justice or Black Lives Matter. I support that 100 percent,” he said. “But I didn’t want people to lose sight of the people that day in and day out” put their lives on the line.

Brown said there was no residual strain between the lawmakers. Still, Weekly’s experience as a Black man on the elected boards on which he served is singular and Weekly said there needed to be more diversity among public officials to better reflect Southern Nevada.

And even then, being an elected official does not make one immune to racism.

“I ran across it a lot. I ran across it in various sectors, from boards I sat on, from interacting with certain officials,” Weekly said. “Yeah, it exists. Trust me.”

‘All politics is local’

When Brown drives by Lone Mountain Regional Park in the northwest valley, the area he represents, he sees baby carriages, joggers, bicyclists, horse riders and sports courts.

“You capture, I think, the essence of a community, a real quality of life,” he said. “That’s rewarding. My fingerprints are on that. I didn’t build it, I didn’t move the dirt, I didn’t construct it. But I was part of it.”

For Brown, “all politics is local” — quoting fellow Bostonian former Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill — which is why he said he never seriously considered seeking higher office despite the suggestions of others. (He ran unsuccessfully for mayor of Las Vegas in 2011.) And he said he has tried to keep the focus on infrastructure, public safety and social service throughout his career.

To a certain extent, he agreed that parks and infrastructure could be his lasting legacy, saying that he oversaw the creation of more than 24 parks in his district between his city and county terms. He also had to contend often with balancing the needs of rural and urban cultures when it came to zoning, approaching huge conflicts with a philosophy of ensuring all voices were heard.

But his elected service, which has spanned nearly a quarter-century, almost never got that far. He won his first race for council by 63 votes, and had he lost, he likely would have made a career in the water district from which he came, he said.

Brown courted controversy in 2013, when as a sitting commissioner he submitted his name to succeed the powerful Pat Mulroy as general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority. Mulroy, however, preferred her deputy John Entsminger for the job, and Brown ultimately withdrew his application.

Before then, Brown and his wife had been contemplating returning to the east coast in the late 1980s, but he said the people he met in Las Vegas early on cemented his decision to stay.

He said it was “special” to be part of a commission that made decisions to support the region’s unique tourist-driven economy and, as the recent board chairman for the Regional Transportation Commission, that officials could never have created billions of dollars for investment in infrastructure through raising the gas tax without first gaining the trust of residents.

During the interview from Brown’s office, his successor — Commissioner-elect Ross Miller — watched as the two had been meeting earlier in the day. Brown said he felt no angst about turning the page because he was “very comfortable” with Miller assuming the baton in District C.

“The transition is going to be fine,” he said. “The northwest is in good hands.”

Weekly shared similar confidence in his elected successor, former state Assemblyman William McCurdy II.

‘Casualty of circumstance’

Brown and Weekly escaped the major missteps that sometimes can derail the careers of public officials, and Weekly’s perhaps most notable controversies came outside of his role as a county lawmaker: the closure of F Street in 2008 and a taxpayer-funded trip to Dallas in 2016.

Weekly recently repeated his long-held contention that he did not authorize the street closure — the street was later forced by public pressure to reopen, at great expense to taxpayers — during Project Neon, and he called it a “very awful experience.”

Yet he was most troubled by the reporting of his $2,400 ethics fine after he accepted $1,400 in plane tickets from the LVCVA for the trip to Dallas with his daughter, saying he felt “helpless” as he became ensnared in the broader gift card scandal.

Weekly insisted that the issue was a miscommunication that did not get resolved in a timely manner and that he was simply a “casualty of circumstance.”

“That should not be the highlight of my career,” he said.

Parting words

As the two prepare to officially move on, they offered advice to their successors, who will be charged with helping guide the county through the economic devastation brought on by the pandemic.

“Be yourself, stay focused and do more listening than talking,” Weekly said he would advise his successor, William McCurdy II, who has been routinely sitting in on District D briefings.

Weekly also said he hopes that McCurdy would push to expand the unincorporated county’s share of territory in the largely incorporated district in order to benefit from residential construction tax dollars and be more engaged in zoning decisions.

Brown was optimistic that the county would emerge better through the present crisis than it did following the Great Recession and the Oct. 1, 2017, shooting.

“This is kind of that third leg, where no one expected it, different from anything we’ve ever experienced,” Brown said. “And yet we’re already seeing signs that this community is going to not only get through it but we will come back bigger and stronger than ever.”

Contact Shea Johnson at sjohnson@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0272. Follow @Shea_LVRJ on Twitter.