Activists still inspired by Declaration of Independence

NEW YORK — Shauna Marie O’Toole is a transgender activist who has organized and attended countless rallies and lobbied New York State lawmakers for legal protections. Convinced that “no amount of science” would win over opponents, she decided that an “emotional statement” was needed, one drawing upon words as rooted as any in American history.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident,” O’Toole wrote, “that all people, regardless of race, gender, religion, immigration or economic status, sexual orientation or gender identity, are created equal, that they are endowed by their government with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.’”

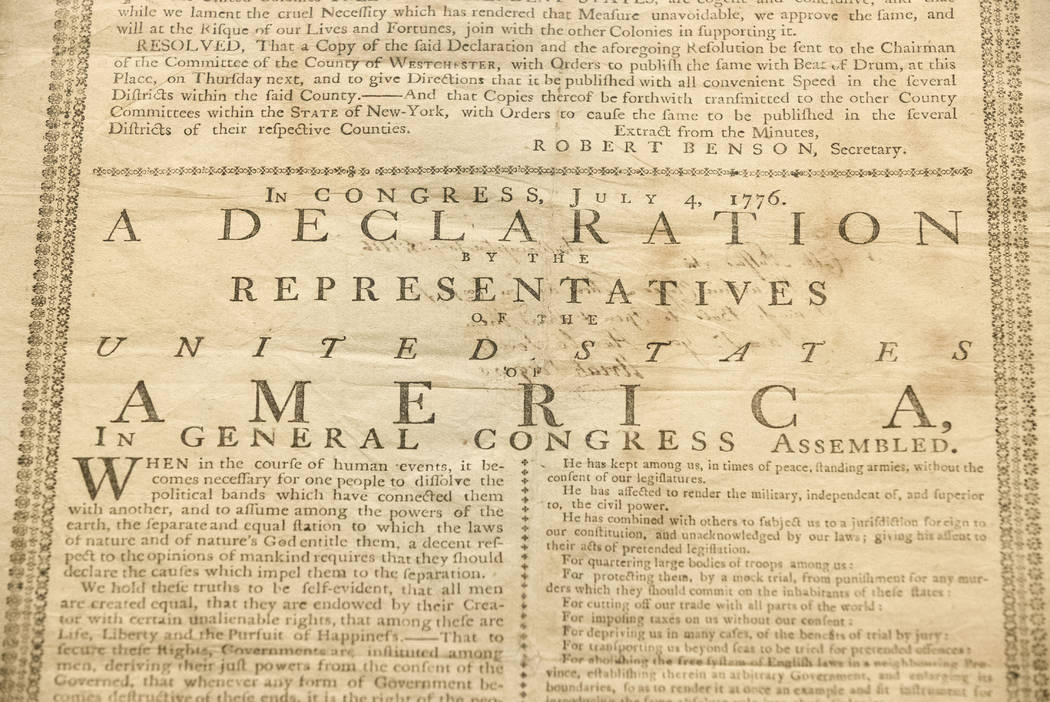

O’Toole, who lives in the Rochester area, received hundreds of responses after she posted her Declaration of Transgender Independence online, from expressions of support to suggestions that Thomas Jefferson would have thought she was crazy. But for O’Toole, the original Declaration of Independence is more than an old document for students to memorize. It’s a starting point for seekers of social justice.

“I think for many activists like myself, it symbolizes what we are willing to do to secure Liberty for ourselves and our posterity,” she told The Associated Press in an email.

Historians debate what the slave-holding Jefferson and his fellow drafters meant by writing “all men are created equal,” but the Declaration has inspired those not mentioned or even imagined in the text. For more than two centuries, it has informed some of the country’s defining rhetoric, from Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, while serving as a template for feminists and labor unions, LGBTQ rights and civil rights.

Fundamental promises

When Americans seek to appeal to the country’s presumed ideals, its fundamental promises, they often turn to the Declaration.

“When Jefferson made his famous statement about equality, he did not really mean that we were created equal individually; the real point was that Americans, collectively, as a people, had the same right to self-government as all other peoples,” says Jack Rakove, whose books include “Revolutionaries: A New History of the Invention of America” and “Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution,” which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1997.

“But over time … the equality statement acquired the aspirational purpose it has held ever since: that each of us is equal in legal status or moral weight or civic ability to everyone else,” Rakove says.

Danielle Allen, author of “Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality,” says that soon after 1776 abolitionists were mentioning the Declaration in their fight against slavery. But its canonization was gradual. Allen and Christopher Warren, a curator of American history at the Library of Congress, both cite the War of 1812 as heightening national pride and anxiety and reviving emotions about the country’s past. The Declaration took greater hold in the 1820s as Jefferson, John Adams and other founders died.

Through much of the 19th century, “declarations” were issued. The Working Men’s Declaration of Independence, issued in 1829, begins, “When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one class of a community to assert their natural and unalienable rights in opposition to other classes of their fellow men. …” The Socialist Labor Party stated in 1895, “When, in the course of human progression, the despoiled class of wealth producers becomes fully conscious of its rights and determined to take them, a decent respect to the judgment of posterity requires that it should declare the causes which impel it to change the social order.”

Used by both sides in Civil War

Before and during the Civil War, North and South invoked the Declaration, but for very different reasons. Historian Ted Widmer, currently working on a book about Lincoln, notes that Lincoln often mentioned the Declaration n speeches even before he was president. When he journeyed from Springfield, Illinois, to Washington for his 1861 inauguration, Lincoln made a point of stopping at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, where he told those gathered that he “never had a feeling politically that did not spring” from the Declaration of Independence.

“The Declaration is the cudgel he uses to beat his political opponents,” Widmer says. “We can be the kind of country that builds upon the Declaration of Independence and grants equality and rights or we can be a slave society.”

Meanwhile, the Confederates cited the Declaration in asserting their right to secede, but scorned the language of equality. Georgia’s leaders borrowed from the Declaration in announcing that they had “dissolved their political connection with the Government of the United States of America.” In 1861, Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens gave what was called the “Cornerstone” speech, insisting his new government’s “cornerstone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery — subordination to the superior race — is his natural and normal condition.”

Abolitionists and civil rights speakers again and again drew upon the Declaration. “Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us?” Frederick Douglass asked in his famous 1852 address “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” In his “I Have a Dream” speech, King insisted the document meant “all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” King read directly from the Declaration two years later, in a July 4, 1965 speech at the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, and praised its “profound, eloquent and unequivocal language.”

The path untaken

Author and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates, in his recent congressional testimony on whether the country should offer reparations for slavery and racial discrimination, cited the Declaration as a reminder of a path untaken.

“Enslavement reigned for 250 years on these shores. When it ended, this country could’ve extended its hallowed principles — life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness — to all, regardless of color,” Coates said. “But America had other principles in mind.”

One of the earliest gatherings for women’s rights in the U.S., the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, concluded with a Declaration of Sentiments: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.” One of the country’s first gay rights organizations, the Chicago-based Society for Human Rights, was founded in the 1920s “to promote and protect the interests of people who by reasons of mental and physical abnormalities are abused and hindered in the legal pursuit of happiness which is guaranteed them by the Declaration of Independence.”

Allen found the Declaration a useful framing for one of her own causes. In July 2016, she wrote a column for The Washington Post about the criminal justice system. She began with the familiar summoning of unalienable rights, “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” before asking that “all legislation erecting the War on Drugs, and turning the American people against one another, ought to be totally dissolved; that the free and independent states and territories have full power to pursue narcotics control through the tools of public health policy.”

“The history of the present War on Drugs is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations,” she wrote. “To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.”