Temple’s inaction allows ‘worship of money’ impression to grow

No one can accuse the trustees of the Hindu Temple of Las Vegas — at least those who are not in prison, or ex-cons, or under federal investigation — of being overly concerned about the questionable image they’re creating for the Summerlin temple.

As reported here on May 7, Dipak Desai, a convicted murderer and former physician who caused one of the greatest public health crises in the history of the United States, continues to work as a temple trustee from his prison cell, helping govern a temple with a mission of promoting religious, moral and spiritual growth for children, adults and seniors.

And former Las Vegas businessman Anil Gupta, who spent 30 months in federal prison after a 2002 conviction for a financial scheme involving the sale of worthless railroad bonds, also has an important say as a trustee in how the temple promotes moral strength in Las Vegas.

Given that trustees are proud to have Desai and Gupta as examples of the best people the temple has to offer — a public official who’s also a temple member believes it’s because of money they donate — it should come as no surprise that they’re not entertaining a temporary suspension of Dr. Prem Reddy’s work as a temple trustee.

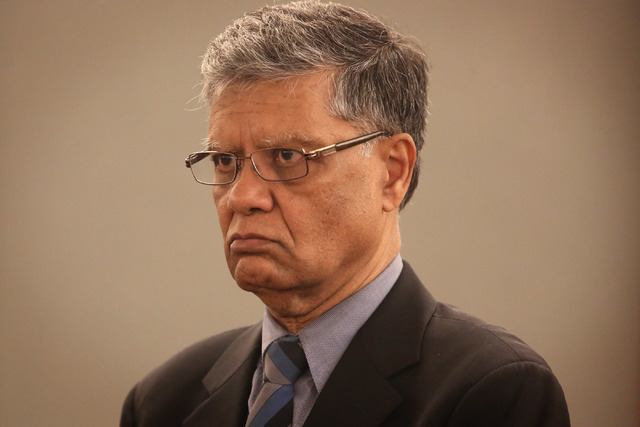

Founder of Prime Healthcare Services Inc., which has 14 hospitals in California, Reddy was accused in a lawsuit joined by the federal Department of Justice on May 25 of “charging for medically unnecessary services. … Schemes such as this one can contribute significantly to the rising cost of health care delivery and create needless patient risk.”

Not long after my last column on the Hindu temple, I walked, as I often do, to the park across from the temple. I overheard people talking about the beautiful place of worship across the street.

“The only thing people there worship is money,” one man said to laughter.

I didn’t think friends of mine who attend there would appreciate the blanket negative generalization of worshipers.

Radha Chanderraj, an attorney and chairman of the board, said Thursday that she supports immediately ridding the nonprofit board of members that call into the question the morality and integrity of the temple.

But she said that after phoning other members of the board, many were reluctant to exercise the power they have. Many, she said, want “to talk about what to do.”

In mid-July.

I asked her if monetary donations by those who’ve had trouble with the law are behind the reluctance by more than 30 other trustees to take action.

“I don’t know,” she said.

Desai’s $250,000 donation was the largest toward construction of the temple in 2001.

In 2007, Desai’s reusing of syringes — which made him pennies of extra profit on each colonoscopy he performed — led to HIV and hepatitis C tests for more than 60,000 Southern Nevadans. In 2013, he was convicted of murder after a patient died, and in 2015, he was convicted of Medicare fraud.

Swadeep Nigam, a member of the temple and editor of Vegasdesi.com, a news portal for South Asians living in Las Vegas, has repeatedly said the failure of the temple’s board to weed out bad actors “is all about the money, nothing else.”

Nigam, a member of the Nevada Equal Rights Commission, said the board’s inaction makes it appear that those who attend the temple are without a moral compass, caring only about money.

He said the temple can exist without Desai’s “blood money” but conceded that donations have fallen off.

The fear of family donations drying up not only could explain both the board’s inaction but also why Chanderraj now says board members are thinking about replacing those they kick off in July with their relatives.

“This whole thing is embarrassing,” Nigam said.

Paul Harasim’s column runs Sunday, Tuesday and Friday in the Nevada section and Thursday in the Life section. Contact him at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5273. Follow @paulharasim on Twitter.