Sarno book reveals good, bad

Going to Shanghai was meant to be an escape, a real vacation where I didn’t work.

One reason for this was simple — the Chinese government made me promise I wouldn’t work before I could get a visa to enter the country. I had to promise I wouldn’t do interviews or any kind of work while I was there. The boss even had to sign a letter saying I wouldn’t work while in China.

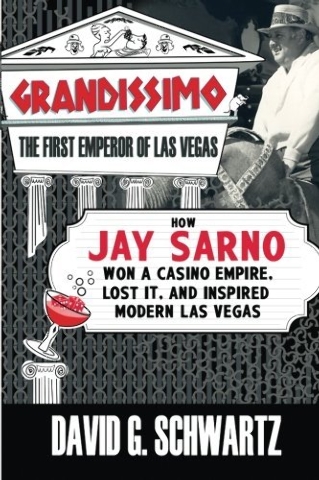

Yet I couldn’t quite let go of the job, deciding to read David Schwartz’s new book about Jay Sarno on the flight over, in case it was column-worthy.

My view is that it’s a great read and a warts-and-all portrayal of Sarno, a dreamer (and a scoundrel) who was the visionary behind Caesars Palace, which reached out to high rollers, and Circus Circus, which went for the mass market, the yin and yang of Las Vegas gaming.

Schwartz, director of UNLV’s Center for Gaming Research, took six years to write it, and it’s well-researched and well-written.

This is no puff piece disguised as a memoir; this is a solid accounting of a man whose dreams became reality, though he couldn’t sustain those dreams by making his business model work. Until now, no one has written a book about Sarno.

Schwartz wrote, “Sarno’s life tells us everything we need to know about how the Las Vegas we all know today came into existence: it’s the story of how a determined man looking for action can change the world, and even make himself an emperor —for a while, anyway.”

Sarno, who died in 1984 at age 62 while on a date, was a degenerate gambler and a man whose lust for women, food and action was insatiable. Schwartz captured that part of him. But he also captured Sarno’s passion to build the first fantasy hotel in Las Vegas — Caesars Palace, which opened in 1966, followed by Circus Circus in 1968.

Yet Schwartz titled his book “Grandissimo: The First Emperor of Las Vegas.” The title is ironic because Sarno was never able to get the funding for Grandissimo, designed as the first megaresort in Las Vegas, but never built. Sarno’s buddy Teamster boss Jimmy Hoffa was no longer around to funnel loans to Sarno, loans that paid for Caesars Palace and Circus Circus.

Schwartz detailed Sarno’s shady dealings, including the skimming at the Circus Circus and the lengthy federal investigations. He didn’t shy away from Sarno’s mob ties. But he also praised Sarno’s efforts to reinvent gaming in Las Vegas, to steer away from cheap rooms, cheap food and cheap entertainment.

One fun tidbit: Caesars opened by charging $14 a night for its cheapest room when $9 a night was the average going rate.

William Bennett, who first leased, then bought Circus Circus and made it profitable by adding 800 hotel rooms, credited Sarno as “the greatest idea man to ever hit Las Vegas,” Schwartz wrote. “Bennett focused on Sarno’s one good idea — opening up the casino business to families and budget travelers — and cut out the distractions like high roller suites.”

Steve Wynn, a protege of Sarno’s, told Schwartz, “When I was younger, I had a hard time seeing through his bombastic and carefree personality — he didn’t look like an artist.”

Yet Wynn said, “If anybody changed Las Vegas, it was Jay Sarno.” And that is from the guy who is credited with creating the megaresort when he opened The Mirage in 1989.

Reading “Grandissimo” was a pleasure because it was a fair, frank and factual history of a crass and complex man, a winner and a loser. It wasn’t a hit piece, nor was it revisionist history. Historians can’t ask for more.

Jane Ann Morrison’s column appears Monday, Thursday and Saturday. Email her at Jane@reviewjournal.com or call her at (702) 383-0275.