National duck stamp competition to land in Las Vegas

Las Vegas won’t get to host a Super Bowl until 2025 at the earliest, so the city will just have to settle for the super bowl of hyper-realistic duck painting.

On Sept. 14-15, some of the nation’s top wildlife artists will descend on the Springs Preserve for the 2018 Federal Duck Stamp Contest, the only juried art show sponsored by the U.S. government.

It will mark the first time the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has held the event in Las Vegas — or anywhere in Nevada.

“This really is a big deal,” said Christy Smith, project leader for the service’s sprawling Desert National Wildlife Refuge Complex in Southern Nevada. “This is likely to be a one-time event.”

The Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Program has been called one of the most successful conservation efforts in history. Since the initiative was launched in 1934, the sale of duck stamps has raised over $1 billion dollars for the acquisition and preservation of more than 6 million acres of waterfowl habitat.

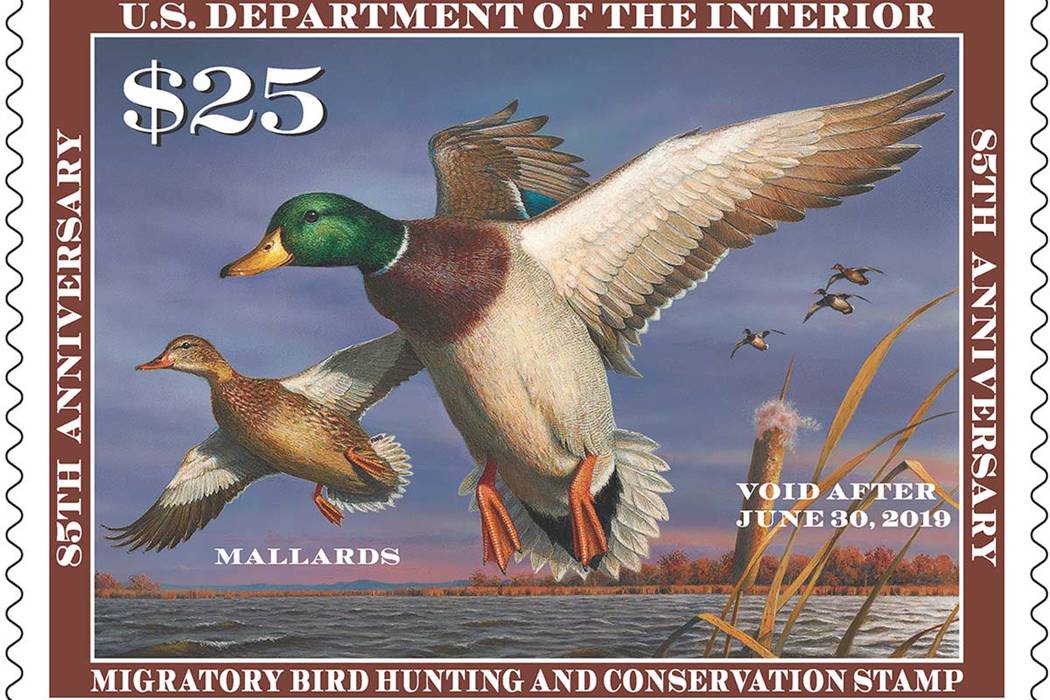

Waterfowl hunters are required to buy one of the $25 stamps each year, with 98 percent of the proceeds earmarked for the protection of wetlands. The stamps are also coveted by birders, conservationists and collectors.

Nearly three-quarters of the land now set aside as Pahranagat National Wildlife Refuge in Lincoln County was purchased with duck stamp revenue.

Where science meets art

The duck stamp program was created by J.N. “Ding” Darling, a Pulitzer Prize-winning political cartoonist from Des Moines, Iowa, who was chosen by President Franklin Roosevelt to lead the U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey, forerunner to the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Darling designed the first stamp, then commissioned works by other well-known wildlife artists until 1949, when the first open contest was held.

This year’s competition drew 166 entries by the Aug. 15 deadline. They will be judged based on their accuracy and composition by a panel of five noted experts in fine art, biology and graphic design.

Smith attended last year’s competition in Wisconsin, and she said the judging is no joke.

At one point, she watched a panelist consult with a bird expert about the brightness of the wings in one of the paintings, and the two of them ended up outside holding a taxidermied duck up to the sun to see if they could reproduce that particular color.

“I can tell you it’s pretty intense,” Smith said. “It can get down to feather counts.”

For this year’s contest, artists were required to depict one of five waterfowl species — wood duck, American wigeon, Northern pintail, green-winged teal or lesser scaup — and incorporate a hunting-related accessory in keeping with the theme, “Celebrating Our Waterfowl Hunting Heritage.”

There is no prize money for winning the competition, but successful artists can turn a tidy profit by selling prints of their work on the surprisingly lucrative market for duck stamp paintings.

Duck stamp dynasty

In recent decades, a trio of brothers from Minnesota have owned the competition. James and Joseph Hautman have each won five times since the late 1980s. Robert Hautman has won three times, including last year, when his acrylic painting of a pair of mallards took the top prize over 216 other entries.

In 2015, the Hautman brothers swept the top three spots in the contest.

Their duck stamp dominance even earned them a mention in the 1996 film “Fargo.”

At least one of the Hautman brothers is expected to attend this year’s contest, though none is eligible to enter, thanks to a rule requiring past winners to sit out for three years.

Smith said there are a number of reasons why Las Vegas fits the bill for a competition like this, despite its dry, desert setting.

The Desert National Wildlife Refuge, just north of the city, is the largest Fish and Wildlife Service site outside of Alaska, while the aforementioned Pahranagat National Wildlife Refuge serves as a key stop for migrating birds on the Pacific Flyway. And then there’s Nevada’s official state artifact: the roughly 2,000-year-old Tule Duck, the oldest known example of a waterfowl hunting decoy.

Still, not everyone was on board with the idea at first, Smith said.

“It took some crossing of fingers to get it here,” she said with a laugh. “It’s usually held in places that have trees.”

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Follow @RefriedBrean on Twitter.