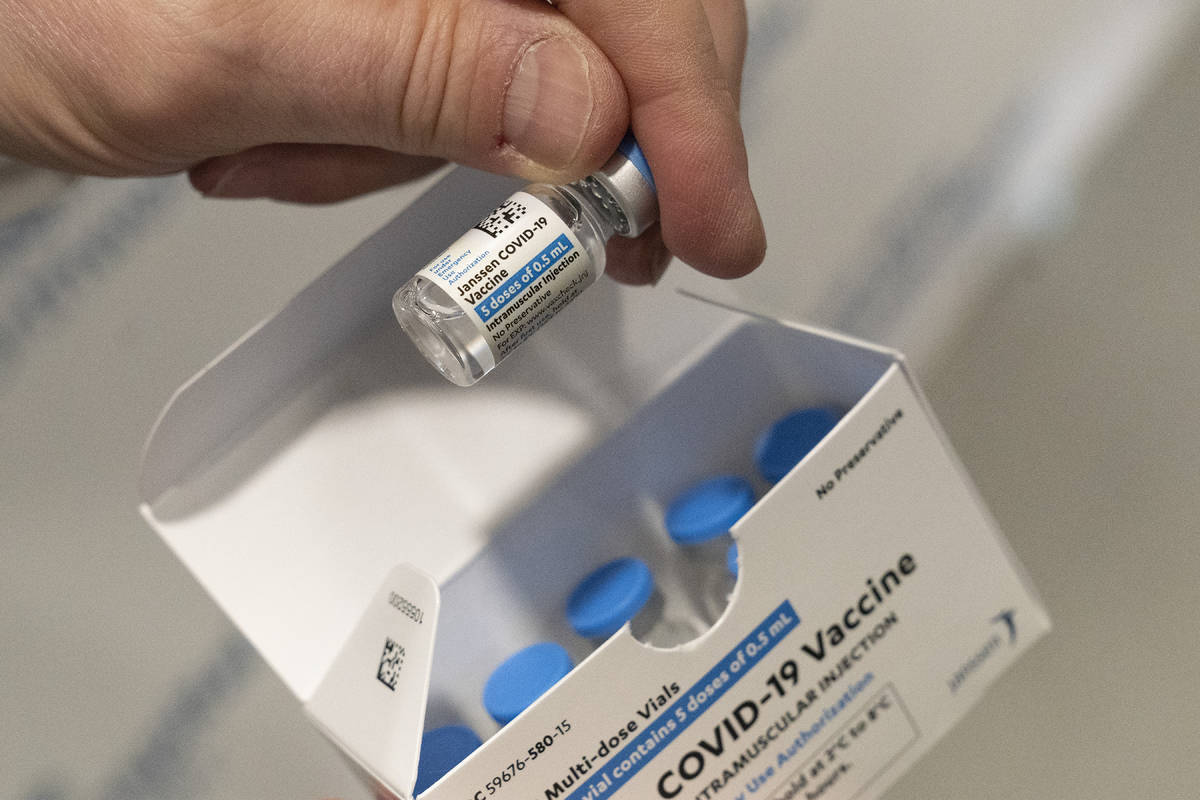

FDA clears way for Johnson & Johnson vaccine to be used again

U.S. health officials have lifted an 11-day pause on Johnson & Johnson vaccinations following a recommendation by an expert panel.

Advisers to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Friday the benefits of the single-dose COVID-19 shot outweigh a rare risk of blood clots.

Panel members said it’s critical that younger women be told about that risk so they can decide if they’d rather choose another vaccine. The CDC and Food and Drug Administration agreed.

European regulators earlier this week made a similar decision, deciding the clot risk was small enough to allow the rollout of J&J’s shot.

Federal health officials uncovered 15 vaccine recipients who developed a highly unusual kind of blood clot, out of nearly 8 million people given the J&J shot. All were women, most under age 50. Three died, and seven remain hospitalized.

Advisers to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said while J&J’s vaccine is important for fighting the pandemic, it’s also critical that younger women be told about that risk in clear, understandable terms — so they can decide if they’d rather choose an alternate vaccine instead.

The panel voted 10-4 to lift an 11-day pause in use of the J&J shot while adding warnings that women and health workers would see in leaflets at vaccination clinics. The group debated but ultimately steered clear of outright age restrictions.

“This is an age group that is most at risk (of the clotting) that is getting vaccine predominately to save other peoples’ lives and morbidity, not their own. And I think we have a responsibility to be certain that they know this,” said Dr. Sarah Long of Drexel University College of Medicine, who voted against the proposal because she felt it did not go far enough in warning women.

The CDC and Food and Drug Administration will weigh Friday’s recommendation in deciding whether to end the pause; the CDC typically follows the guidance of its advisers and CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky has promised swift action.

The committee members all agreed the J&J vaccine “should be put back into circulation,” panel chairman Dr. Jose Romero, Arkansas’ health secretary, said in an interview after the vote. “The difference was how you convey the risk … It does not absolve us from making sure that people who receive this vaccine, if they are in the risk group, that we inform them of that.”

European regulators earlier this week made a similar decision, deciding the clot risk was small enough to allow the rollout of J&J’s shot. But how Americans ultimately handle J&J’s vaccine will influence other countries that don’t have as much access to other vaccination options.

Dr. Paul Stoffels, J&J’s chief scientific officer, pledged that the company would work with U.S. and global authorities “to ensure this very rare event can be identified early and treated effectively.” J&J already was working with the FDA on a warning label for the shot.

At issue is a weird kind of blood clot that forms in unusual places, such as veins that drain blood from the brain, and in patients with abnormally low levels of the platelets that form clots. Symptoms of the unusual clots, dubbed “thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome,” include severe headaches a week or two after the J&J vaccination — not right away — as well as abdominal pain, nausea.

The government initially spotted six cases of the rare clots, with nine more cases coming to light in the last week or so. But even the first needle-in-a-haystack reports raised alarm because European regulators already had uncovered similar rare clots among recipients of another COVID-19 vaccine, from AstraZeneca. The AstraZeneca and J&J shots, while not identical, are made with the same technology.

European scientists found clues that an abnormal platelet-harming immune response to AstraZeneca’s vaccine might be to blame — and if so, then doctors should avoid the most common clot treatment, a blood thinner called heparin.

That added to U.S. authorities’ urgency in pausing J&J vaccinations so they could tell doctors how to diagnose and treat these rare clots. Six patients were treated with heparin before anyone realized that might harm instead of help.

Dr. Jesse Goodman of Georgetown University closely watched Friday’s deliberations and said people should be made aware of the clotting risk but that it shouldn’t overshadow the benefits of COVID-19 protection.

“We need to treat people as adults, tell them what the information is and give them these choices,” said Goodman, a former vaccine specialist at the FDA.

Two-dose vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna, which are made differently and haven’t been linked to clot risks, are the mainstay of the U.S. vaccination effort. But many states had been counting on the easier-to-store, one-and-done option to also help protect hard-to-reach populations including people who are homeless or disabled.

The CDC’s advisers struggled to put the rare clot cases into perspective. COVID-19 itself can cause a different type of blood clots. So can everyday medications, such as birth control pills.

The side effect debate isn’t the only hurdle facing J&J. The FDA separately uncovered manufacturing violations at a Baltimore factory the company had hired to help brew the vaccine. No shots made by Emergent BioSciences have been used — J&J’s production so far has come from Europe. But it’s unclear how the idled factory will impact J&J’s pledge to provide 100 million U.S. vaccine doses by the end of May and 1 billion doses globally this year.