Miracle Survival

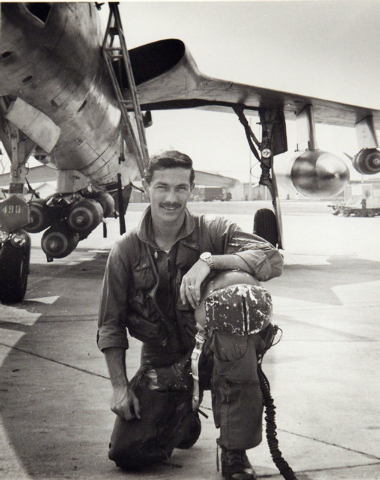

Don Harten believes God had a plan for him, but dying in the Vietnam War wasn’t part of it.

In the end, it was a miracle that he survived, not just the five combat tours and more than 1,000 hours he spent flying big bombers and fighter jets, but especially that day in 1965 during the first B-52 raid.

His plane never reached the target, a rubber plantation north of Hanoi. Instead, on the same day — June 18, 1965 — he survived a midair collision and another crash of the plane that had rescued him from the roily South China Sea.

“My odds of living through that war were damned near zero,” the gravelly-voiced, 74-year-old Air Force veteran said in a late October interview.

He has been living in Las Vegas since 1997.

MISSION: ARC LIGHT ONE

The mission, known as Arc Light One, is the title of the book he wrote about his experience. Arc Light was the code name for B-52 operations throughout the war. This, the first one, was a response that President Lyndon B. Johnson had ordered after the Viet Cong’s Feb. 7, 1965, attack on a Special Forces camp near Pleiku, South Vietnam, that had killed 28 military advisers.

Although the massive B-52s could drop nuclear bombs, Harten’s unit at Mather Air Force Base near Sacramento, Calif., had been practicing with conventional, World War II-type “iron bombs.” The crews’ skills were honed for the mission. The B-52 that Harten flew as co-pilot was the fifth to land in Guam.

They were supposed to take off 12 hours after they refueled and were loaded with bombs. Then they were to fly low over the South China Sea toward Haiphong and Hanoi, “then pop up to 1,500 feet and release more than 1,530 bombs — 51 from each of 30 B-52s — and literally vaporize the Phuc Yen airfield. They had no defenses to shoot down B-52s at that time, especially at night, especially low-level,” Harten said.

“The war would have ended right there most likely.”

Instead, the mission was delayed by more than four months and the target was changed to a rubber plantation in the jungle.

“There was nothing out there. They were told where we were coming and when we’d be there,” he said, reflecting on the mindset of decision-makers who were charting a politically correct course for the undeclared war.

As a result, Harten said, there were flaws in the refueling strategy, with timing to meet airborne tankers thrown off by tail winds from a typhoon.

“A bunch of us first lieutenants complained about that. We bitched and moaned and cried and whined and everything else. They said, ‘Well, you weren’t on the thousand-plane raid to Hamburg’ ” during World War II.

“We said, ‘Listen, you’re fighting two wars ago. We’re talking about now. You need to do some modern things with these modern jets, because they travel rather fast.’ So we went out there, and the typhoon had sucked us inland. We were nine minutes early,” he said.

CRASH OF THE B-52S

To adjust the arrival time for the tanker rendezvous, the pilot leading some of the B-52s made a 360-degree turn to chew up eight minutes.

Harten was at the controls because his pilot, Jim Gehrig, was taking a break before the refueling operation. Harten called on the inter-phone for Gehrig to hustle back, because Harten and the radar navigator realized they would be facing other planes head-on as the lumbering formation circled. Their plane’s airspeed, combined with that of the fast-approaching string of B-52s, meant they were on what amounted to be a 1,000-mph collision course.

“So we get halfway around the turn and radar navigator Terry Lowry said, ‘We’ve got beacons at 4 miles and closing fast.’ I looked out and here comes a B-52. Then I see this B-52 turn into a gray shape and its drop tank is going to hit me in the face, 18,000 pounds of jet fuel.”

At that instant “everything turned into slow motion, real slow motion. I mean seconds became minutes, and we only had a couple seconds,” Harten said.

It seemed like the approaching bomber “slowly got larger, and then it slowly fell underneath our cockpit and that great big six-story tail came sliding by on the right of us.”

At first he thought the planes had missed each other. Suddenly there “was a big bounce and then explosions. It blinded me, and I didn’t know that our right wing had blown off.”

Harten’s plane dropped straight down while the other, with its tail knocked off, went into a spin. Barely able to see, he grabbed the yoke.

“I kept thinking, ‘If we just lost our wing tip I can still fly this thing.’ Then, somebody ejected and I thought it’s time to jettison the airplane and get out, because it’s starting to come apart.”

He squeezed a handle to jettison the seat, but the lever was stuck. “I looked down and said, ‘Fire you son of a bitch!’ And ‘bam.’ Just then it fired.”

The whiplash with a four-pound helmet on his head chipped a vertebrae in his neck. Another explosion sent shrapnel flying into his leg.

“Then the parachute opened and I looked down. The whole ocean was on fire.”

DOWN TO THE SEA

The canopy started spinning, getting smaller as he dropped from 15,000 feet. The large fires on the sea from several hundred thousand pounds of jet fuel sent up a heat-filled cloud. He tried to slip out of its way but the chute kept spinning.

“Of all things, I thought of the law of conservation of angular momentum from college physics,” he said.

So he pulled another handle, and a small, yellow life raft dropped on a 50-foot cord followed by a survival kit. Dangling below him, they stabilized the spin. “Conservation of angular momentum worked.”

As he descended, the flames on the sea began to subside.

“To this day it seems like a dream,” he said. “It just doesn’t seem real. So I’m looking down at the ocean and I’m praying to God: ‘Oh save my sweet ass.’ And he said to me, and I swear I heard him say, ‘Save it yourself. I want to see how you’re going to handle the situation.’ ”

The typhoon-powered waves reached 40 feet tall, and the fierce wind blew his parachute at an angle.

“Finally I hit the water, but I didn’t go in except up to about my waist because I suddenly set a world record for water skiing,” he quipped. “I was drug sideways, and it was spinning me. And every time I was face down I would swallow a whole lot of water.”

He struggled to pull the parachute release rings, but they wouldn’t budge. With both hands he tugged on one with all his strength until it released, causing the chute to whip away and leaving him connected to it on one side.

He swam to the tiny raft. It was a tight fit. He pulled in the survival kit only to find items such as wool socks, a ski mask and sleeping bag for enduring a winter Arctic landing, but not much for the South China Sea in the summer. The turquoise water carried his raft up and down. In minutes he was seasick.

He saw an orange-and-black freighter pass within a quarter mile, but it was dark and he had nothing to signal it. Then suddenly he went down, pulled underwater by the still-connected parachute. He grabbed a knife from his thigh pocket and slashed the cord and his fingers too.

“Now I’m bleeding and I’m worried about sharks.”

At sunrise he blew more air into the raft’s stem to reinflate it.

“I just sat there thinking, ‘You know for the first time in my life since I was an infant, I’m now totally dependent on somebody else for my life.’ ”

CRASH OF THE RESCUERS

In a while a low-flying air tanker circled overhead. Its crew dropped a large life raft out the cargo door within a few hundred yards of him. But the waves, cresting at 25 feet, were too tall for him to see it.

After five hours, a seaplane landed and taxied toward him.

“They kind of pulled in backwards. I see this float. It had a tie-down ring on the back of it. I grabbed ahold and wasn’t going to let go. The next thing I know, this young kid popped out of the water. I said, ‘Are you Neptune?’ ”

The crew pulled him inside the plane and bundled him in a blanket. Only three others out of 12 crew members from the B-52s had survived the midair collision. As the seaplane started to take off, Harten noticed water coming up from the floor. The plane’s fuselage had cracked while landing in the rough sea.

“We tried to take off six times, but we hit the waves and couldn’t make it. The last time we finally bounded into the air and got about 150 feet and crashed. It was solid and nasty. We were bobbing around, and the plane is really filling with water.”

Then he looked across the water and saw the same black ship with orange trim that he had seen earlier, the Norwegian freighter, Argo. The crew sent over a long lifeboat that hauled them to the ship.

Harten said it was “survivor’s guilt” that made him keep flying as a fighter pilot in F-105s and F-111s.

He said the Vietnam War was worthwhile for the effort to curb the spread of communism, but not for the way American politicians made the military fight it.

“There are things that changed in me. I found out what was important. You see these guys right here. Those are the guys who were important, the guys who died,” he said, clutching a photograph of his crew.

That’s what he’ll be thinking about on Veterans Day.

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.