Letters reveal father’s secret past in atomic bomb tests

It’s been 66 years since Linda Thornley’s father witnessed the explosions of two atomic bombs.

Her father, Ed B. Thornley, died in 2004 without sharing the experience with anyone because of the secret nature of his work during a career in radio communications that spanned the Cold War.

Even his family never knew exactly what he did or what he observed during Operation Crossroads, the code name for the nation’s second and third nuclear weapons tests and the first conducted at sea.

The nuclear bombs, dubbed Able and Baker, were exploded at the North Pacific’s Bikini Island lagoon to see how atomic bombs dropped from aircraft or detonated underwater would affect a flotilla of U.S., Japanese and German warships.

The so-called "Guinea pig" ships, more than 90 World War II vessels and boats destined for the scrapyard, were anchored with their locations pinpointed for accurate recording by hundreds of still and video cameras on aircraft and towers around the lagoon. Thousands of detection instruments were used.

The battleship USS Nevada was painted red so it could be tracked during the atomic air burst 520 feet above it. Goats, sheep and other animals were loaded onto others to gauge the effects of blast and fallout on living things. In all, 220 ships, 160 aircraft and 45,400 men, mostly sailors, participated in Operation Crossroads.

"He did not talk about the Bikini blast at all when I was growing up. He mentioned it a couple times, saying that he had been there, but no details. Nothing," Thornley said.

Fortunately, her dad had documented the experience in letters that he wrote to his parents in Wisconsin from the USS Rockingham, a Navy attack-transport ship where he was an electronics technician mate second class.

Only recently did Thornley feel comfortable enough to sort through her father’s personal things. When she did, she was pleasantly surprised and vowed to share this part of Cold War history as a tribute to her dad.

"I found an envelope. It says Bikini letters. So I opened it up. I found all these wonderful, glorious notes that he wrote at the tender age of 19 to my grandparents."

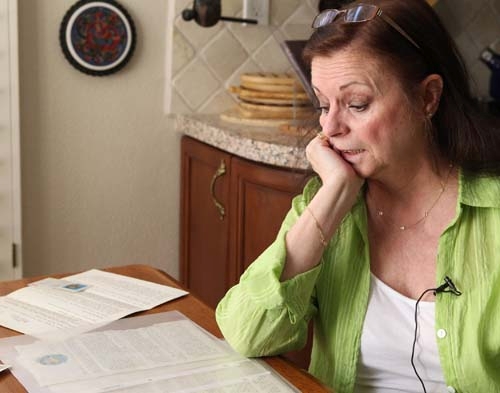

For Thornley, a retired lawyer who moved to Las Vegas in 2002, her father’s letters tugged at her heartstrings.

"I’m getting weepy now because I found out all this about my dad I didn’t know," she said Wednesday at her southwest Las Vegas home.

The Able and Baker nuclear tests involved plutonium devices that were detonated to produce the same caliber explosion as the 21-kiloton "Fat Man" bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, near the end of World War II.

"It was a big deal and I shared that excitement. He was in a moment of history," she said about the atomic bomb blasts. Each had the equivalent explosive yield as detonating 21,000 tons of TNT.

The USS Rockingham was positioned 20 miles from ground zero during the Able airdrop shot on July 1, 1946, although records kept by the National Nuclear Security Administration in North Las Vegas list the detonation date as June 30, 1946, to reflect Greenwich Mean Time. The Rockingham was plying the ocean 10 miles away for the underwater Baker detonation on July 25, 1946, off Bikini. In his letters, her dad described the detonation as being radio-controlled from the USS Cumberland Sound. The signal triggered the detonation of the device, which he said was carried by a "landing boat."

According to a federal defense agency, the Baker device was suspended in a waterproof caisson, 90 feet below a small vessel in the center of the 68-ship target fleet.

That explains the colossal upwelling of the lagoon that was captured on film and appeared as a giant, exploding fish bowl.

"What a thing to see!," Ed Thornley wrote on July 25, 1946.

"First a huge ball of fire out of the sea, carrying a column of water. It had hardly risen when the whole target area seemed to rise out of the water in a huge column. It shot five thousand feet into the air, and then the water poured down like Niagara Falls. The whole target area was then blanketed with a grayish pink cloud."

Minutes before the Able blast, "they were told to cover their eyes and hit the deck," Linda Thornley said.

"Then all of a sudden they get up and the next day they’re out taking pictures, and looking and checking things out," she said. "From what we know about nuclear information now, nobody in the world would be doing anything like that in this day and age."

Four months before the Able shot, 167 native Bikinians were permanently evacuated to Rongerik Atoll, where the Navy had built 26 frame houses for them.

In a letter he wrote on July 27, 1946, Thornley’s dad offered his thoughts on the atomic bomb’s power and devastation.

"A lot of damage can happen without being noticeable from the outside, such as small openings made in the hulls, propeller shafts being bent, and the whole hull sprung out of shape. Of course damage like that isn’t spectacular, but it would be enough to put the ship in a Navy yard for a long time.

"And also casualties among the crews would be terrific. So I think they have a very terrible weapon on their hands. I hope they never have to use it."

Thornley said that passage "kind of gives me goose bumps."

"Obviously the weapon had been used twice, in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But this was the first time they actually saw the damage that was going to be created.

"And thinking about that, they didn’t even realize the stuff that they were putting into the stratosphere, the nuclear junk that has been going up everywhere. They had no idea about that part. They were looking at the physical damage to the ships and the potential damage to human life."

After his stint in the Navy, Thornley went to college on the GI Bill and pursued a career in communications and electronics. He landed a job with Collins Radio in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, where Linda was born in 1952. He later worked for TRW in Redondo Beach, Calif., where he retired in 1992.

"During his entire career, everything was very secretive. Everything as very quiet. And, as I said, he didn’t even really talk a lot about being in this blast to use when we were growing up," Linda Thornley said.

"So I wanted to share part of that, that he was never able to share because of his occupational profession. He did a good thing. It was wonderful and I’m proud of him."

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers @reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.