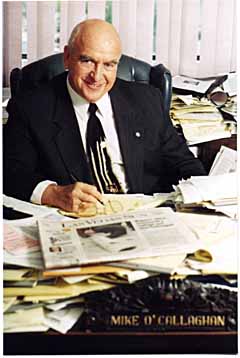

Mike O’Callaghan

He might just be the most popular governor Nevada ever had. Donal “Mike” O’Callaghan charged out of obscurity like a Minnesota moose, whipped the anointed candidates, and through two terms of office, set an example of hardworking government responding to the needs of ordinary Nevadans.

In the 20 years since, he has pursued a second career as a newspaper executive and an opinionated columnist who has punished many a bureaucrat for failure to meet his high standards of governmental conduct.

O’Callaghan’s parents, Neil and Olive, lost their mortgaged farm in the Depression, took up marginal land near Sparta, Wis., and tore subsistence from thin soil. “We had cows and sold cream. We raised our own food, and ate a lot of venison,” said O’Callaghan in a 1999 interview in his executive office at the Las Vegas Sun.

But for World War II, O’Callaghan might have been a farmer like his dad. The government wanted to expand an artillery range, condemned the farm, and didn’t pay enough to buy another. Neil O’Callaghan returned to his old trade as an operating engineer. Young Mike joined the Marine Corps as soon as it would allow him, at the age of 16, but that was a little too late for World War II. He was assigned to guard prisoners on Guam, and finished his hitch as a sergeant.

His father had relocated to Hanford, Wash., and his mother taught school over the state line in Idaho, so O’Callaghan joined them, supporting himself as an ironworker and going to Boise Junior College. He kept in shape by boxing. Then a group of friends from Boise decided to join the Air Force, and O’Callaghan, attracted by the opportunity to study new technology, joined them. He was trained as an intelligence officer and stationed in Alaska.

To his consternation, the Korean War broke out, leaving him stranded in another military situation where he was unlikely to see any action. Then, because the new war was using up infantry platoon leaders faster than America was training them, a new policy came out authorizing interservice transfers to the Army for military men who could pass a qualifying test. O’Callaghan jumped on the chance. Once transferred, he signed a waiver releasing the army from its commitment to send him to officer candidate school, and went to Korea as a private.

O’Callaghan explained the decision that put him into an ugly war and his third branch of the military. “I wanted to get into combat. I had been trained for it, and I thought, why send some kid over when I had that training?” As for becoming an officer, he figured he would get a battlefield commission anyway. He did become a platoon leader, even though he was still a sergeant, because three successive lieutenants were killed or wounded.

O’Callaghan won a Bronze Star with the “V,” denoting valor, for an action on Dec. 24, 1952. But on Feb. 13 he paid a high price for courage. A military document notes, “While his company was being subjected to a barrage of heavy artillery from Chinese Communist forces during a night attack, Sgt. O’Callaghan was informed that men on an out-guard post had been cut off by this enemy action. Immediately … he voluntarily exposed himself to enemy fire, located the men and brought them, together with a wounded member, safely back to the trenches.”

Shortly thereafter, he took a direct hit on the lower leg from an 82 mm mortar round. “It killed my squad leader, a kid named Johnny Estrada,” remembered O’Callaghan 46 years later, showing no expression. He rigged a tourniquet out of telephone wire, using a bayonet to twist it tight around his mangled leg.

The subsequent official account relates: “He crawled back to the command post and, from that position, controlled platoon action for the next three and one-half hours, giving orders over the phone. Not until the enemy had withdrawn did he permit himself to be evacuated.”

The Army figured that was worth a Silver Star, and O’Callaghan went home a hero. His left leg was amputated below the knee, his hip was broken, but by summer he was back working construction.

O’Callaghan finished a master’s degree in 1956 at the University of Idaho, and was hired to teach government, history and economics at Basic High School in Henderson. He helped found and run the Henderson Boys Club, teaching factory-town kids to box. David Zenoff, then judge of the Clark County juvenile courts, began releasing some kids to his custody. When a position came open as director of juvenile court services, Zenoff hired him. O’Callaghan changed the style of the agency, hiring people from a wider variety of ethnic backgrounds, while they were still young and energetic. “I got them into the idea of working nights, instead of shuffling papers. Going to dances, going to hangouts, knowing the community.”

Meanwhile, O’Callaghan had become active in Democratic politics. Justice of the Peace Jan Smith of Goodsprings, who knew him literally from the day he moved to Henderson, said, “When he became county chairman a lot more people came in. He opened the process to ordinary people. You didn’t have to wear your Sunday best to come to a meeting. Not that there ever had been a rule that you did, but people just felt comfortable with him. There had always been black people in the party, but before Mike there was, if not physically, an intellectual line, a way of thinking, that separated them from the rest of the party.” Under O’Callaghan, that line was all but erased.

Gov. Grant Sawyer, reorganizing state government, hired O’Callaghan in 1963 to gather seven related departments into what is now called the Department of Human Resources. In 1964 O’Callaghan took a job in Washington organizing Job Corps conservation camps throughout the country. Then President Lyndon Johnson named him regional director in the Office of Emergency Preparedness, over Nevada, Utah, Arizona, California, Hawaii and the Pacific possessions and trust territories.

Although he resigned the job when Richard Nixon took office, he maintained a lifelong interest in emergency services, and later, through the National Council of State Governors, backed President Jimmy Carter’s legislation to unify various federal disaster-relief bureaus into the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA.) Carter even offered him the chance to head the agency, but by then he was back in Nevada, and disinclined to return to Washington.

Although the amount of power vested in FEMA has caused nervousness in conservative circles, O’Callaghan said, “FEMA can’t go anywhere without the governor of the affected state asking the president to send it. So the black-helicopter nonsense is not even worth discussing.”

O’Callaghan had made one false start toward the statehouse in 1966, running for lieutenant governor in a crowded Democratic primary eventually won by Las Vegas lawyer John Foley. Foley was defeated in the general election by the Republican candidate, Ed Fike.

In 1970 O’Callaghan ran for governor.

“The Democratic powers had already picked their man, Hank Thornley. And I would go to political affairs and they would introduce Ed Fike as `the next governor of Nevada.’ ” He liked both men, said O’Callaghan, and in fact attempted to hire Thornley for a state position later on. But, he said, “I figured I could do as good a job … I knew I could make government run.”

He won the primary as a dark horse and ran in the general as the underdog.

Fike rode in professionally managed motorcades that showed up exactly on time for the rubber-chicken dinners in Tonopah or Elko. But when O’Callaghan showed up, unannounced, in some bar or lunch counter, somebody already knew him from his visits as a state official or, in White Pine County, in a relief effort after devastating floods. And they introduced him on a more personal level.

Roy Vanett, city editor for the Review-Journal in those days, remembered seeing him on the corner of Main and Bonanza on a blistering hot day, greeting motorists at the stop light. “When I came back from my errand he was still there,” said Vanett. That was when he decided O’Callaghan might win.

“Ed made his own fatal mistake when he made a promise to remove the sales tax,” said O’Callaghan. “That night I was on radio pointing out he couldn’t remove it because it was voted on by the people. Then I went to bed early and slept soundly.” O’Callaghan won by a vote of 70,697 to 64,400.

O’Callaghan worked just as hard being governor as he did getting elected, and he expected the same of his appointees. Jan Smith, who became manager of his Southern Nevada office, became used to phone calls on business at 3 a.m., when the governor had already begun his workday. Her low-budget weekend retreat, an old miner’s shack in Pioche, had no phone. “That didn’t make any difference because he figured out there was a police station wherever you went.” A deputy would show up with a message to call the governor from a pay phone.

O’Callaghan would show up unannounced at state-run facilities. “You learn little things that way,” he explained. “If you go into a state institution and it smells like urine, you know it isn’t being run right.” He ate the same food inmates ate, at the tables they used every day. Once, as he was having breakfast in a mental institution, an inmate realized O’Callaghan was new and asked what he did for a living. “I’m the governor,” said O’Callaghan.

“You stop right there,” said the inmate. “We’ve had two or three other guys in here said that and if you keep on they’ll never let you out!”

He played political hardball to get things people needed. Minorities had been trying for years to get an open-housing law in Nevada. The bill was once more locked up in committee. “I was able to get it out of committee by convincing one of the senior senators that he was going to have problems getting a facility he wanted” unless that bill was unlocked.

Mary Hausch, who covered the Nevada Legislature while O’Callaghan was in office and now teaches journalism at UNLV, remembered O’Callaghan fought for the Equal Rights Amendment, simply because he believed in it. “He always mentioned it in his State of the State speeches, even though he knew it would never pass in Nevada. A lot of governors would not have championed something that wasn’t going to happen.”

He appointed women to positions of authority and in January 1978, beginning his eighth and last year in office, claimed that the percentage of state supervisory and administrative positions held by women had almost doubled in the previous four years.

One theme of his administration was making state services available in all parts of the state. O’Callaghan was the first governor from Southern Nevada, and was proud of building a prison at Jean, where the families of inmates from Las Vegas could maintain ties more easily than they could when the only prison was in Carson City. But when facilities were built in Las Vegas to offer psychiatric and psychological services for children, Reno got some as well.

Being an amputee, O’Callaghan noted, he was very aware of a need to provide maximum rehabilitation for injured workers. “This isn’t just more humane, it makes economic sense,” he said. So he counted construction of the Jean Hanna Clark Rehabilitation Center in Las Vegas as one of his major accomplishments.

He increased funding for special education programs. He created a state Consumer Affairs Office. His administration created the Nevada Housing Division, which provided low-cost loans to help Nevadans buy their own homes.

An amendment to the Nevada Constitution, limiting governors to two terms, took effect after his election, so O’Callaghan was the last who could have lawfully sought a third. He considered the idea but rejected it. “Four years wasn’t enough. Eight years is about right,” he told Hausch for a retirement story. “After that you start to defend your mistakes rather than change things.”

Moving back to Las Vegas, he accepted a job from the late publisher, Hank Greenspun, as an executive at his Las Vegas Sun. In 1981 he bought the Henderson Home News and its sister paper, the Boulder City News, which are run by his son Tim.

“The Sun is like a bulldog,” said O’Callaghan. ” If it gets on something it stays on it until it is resolved. And some things never get resolved. They have never gotten off nuclear waste.”

In two decades at the daily newspaper, he has held a number of positions and is now executive editor and chairman of the board. Some who have worked directly with him call his management brutal. “He breaks every rule in the book of human relations,” said one, in return for a blood oath of anonymity. “He’ll yell, curse, ream people out, and he gets away with it because of who he is.”

Yet the same employee expressed deep respect for O’Callaghan as a man of integrity, wonderful political sources that benefit the news staff, and the willingness to show the political ropes to those who have to cover politics. He admitted liking him, and fearing him, simultaneously.

And maybe that’s the essence of O’Callaghan. Right hand ready for a handshake. The other for a left hook.