Late detective hailed for cracking of tough cases

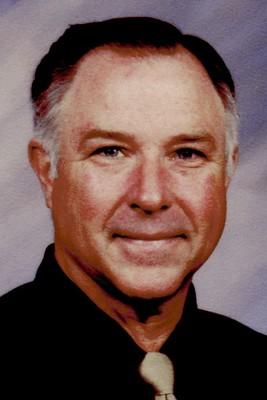

Detective David Mesinar spoke for the dead.

He worked Las Vegas homicide for 10 years.

There were the big cases: four killed at an Albertsons grocery store by a drugged-up gunman; a daughter who killed her mother, put her in a garbage can and let her body rot in a storage facility; a murder for hire involving one of the nation’s wealthiest families.

There also were smaller ones. Yet the 31-year veteran of the Metropolitan Police Department stewed over them all at work.

And, though he tried to hide it from his wife, she knew his mind was always putting together the puzzles at home, too.

Mesinar took his job to heart as he grieved with victims’ families. After he retired, the itch remained and he went back to the police department to solve cold cases.

He was a steak-and-potato- eating cop, hard-nosed and broad-shouldered. At 6-foot, 3-inches, Mesinar was intimidating to the bad guys. Police were glad to have him along when the job got physical.

Now others are speaking for him.

Mesinar died May 27 at his cabin in Beaver, Utah, the victim of a pulmonary embolism, his family said.

He was 61.

“He was a guy who put his heart and soul into catching killers,” said Glenn Puit, a former Review-Journal police and court reporter. “He was all about finding justice for victims.”

Mesinar was a key source for Puit’s book, “Witch,” the story of Brookey Lee West.

West was convicted of murdering her mother, Christine Smith.

In February 2001, authorities found Smith’s body sealed in a plastic garbage can inside a Las Vegas storage unit after the can sprang a leak and an overpowering stench and liquid remains seeped out.

“He was a real hard-nosed homicide detective who cared about Las Vegas,” Puit said. “His motto was: The victim’s can’t speak, so you have to do right by them.”

Mesinar worked to solve the murder-for-hire scheme that involved the husband of a du Pont family heiress.

Lisa Dean Moseley, a direct descendant of the founder of the DuPont Co., the largest U.S. chemical company, was married to Christopher Moseley.

He had paid $15,000 for the 1998 slaying of 45-year-old Patricia Margello, his stepson’s girlfriend, whose body was stuffed in the air-conditioning vent of a Las Vegas motel room. Three others also were convicted in the case.

Mesinar also helped put Zane Floyd on death row.

Floyd used a shotgun June 3, 1999, to kill four Albertsons employees.

Mesinar eventually burned out — police officers say everyone eventually burns out in homicide — and retired.

“He couldn’t stay away,” Puit said. “So he went back to work cold cases. It’s meaningful work (solving homicides). There’s no other job in the world of public safety that’s as important.”

Mesinar’s wife, Linda, recalled how her husband would continue to work cases in his mind, even at home.

“He was restless when he was investigating a case. When he did get home, he was able to take care of himself and get the proper down time. But he was restless in the fact that you could just see him with these unfinished loose ends. … Knowing somebody’s guilty and not being able to get the proof he needed bothered him in some cases.”

Kevin Manning, Mesinar’s sergeant for most of his time in the homicide unit, said the detective’s imagination helped him excel.

“He was one of the best at using that creativity and coming at it from a different angle,” he said.

Manning called Mesinar a great interrogator, breaking down victims with a low-key, empathetic style.

“He would come at them and take them by surprise. He could get his dander up when necessary,” Manning said.

Linda Mesinar didn’t often see that side of her husband. He was more the blue-eyed teddy bear, tender and gentle at home, she said.

That was the side he showed to victims’ families, Manning said.

On Friday, family and friends gathered at the Mesinar home in the southwest valley for some storytelling.

Linda Mesinar recalled the last time she listened to a police scanner.

It was in the mid-1980s. The couple had just married. Her husband, a narcotics detective at the time, was about to participate in a buy-bust.

“I wanted to participate and be a part of his life and was interested in what he was doing,” she said.

Just before going in, Mesinar asked for a “Code Red,” or all silence, on the radio.

The radio was quiet for a moment, and then Linda Mesinar heard her husband shouting, “N-842 to control.”

But there was no answer. He kept yelling, and an operator eventually answered. Mesinar yelled that shots had been fired.

“I was just holding my breath, and I was thanking the Lord I was hearing his voice and not somebody else’s, because I knew he was OK if he was actually on the radio,” Linda Mesinar said.

Then there was the time in July 1996 when Mesinar’s partner, Mike Bryant, accidentally shot him in the butt.

Manning said the officers were at the shooting range and Bryant’s gun discharged. Manning said it was one of the scariest moments of his career, watching Mesinar in agony as blood seeped through the rear of his pants.

All they had on hand at the range to stop the bleeding was some gauze and a Kotex pad, Manning said, trying to stifle his laughter.

“After that, they have a full trauma kit at the range,” he said.

Mesinar, who was born in California, was in the Air Force during the Vietnam War and ended up at Nellis Air Force Base. That’s when he decided to make Las Vegas his home.

He had a fondness for the community, his wife said: “He knew every nook and cranny of this town.”

He consulted for the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, spending nine weeks in Mississippi and Louisiana working to reunite families after Hurricane Katrina.

Linda Mesinar said her husband never showed any signs of heart problems. But last Sunday he came into the bedroom of their cabin in Beaver and said there was something wrong.

Friends performed CPR on him for 45 minutes as paramedics rushed to the secluded area, Linda Mesinar said. A physician told her he was probably gone in seconds, she said.

The couple would have celebrated their 24th wedding anniversary this month.

Mesinar is survived by two sons, a daughter, a step-daughter and 11 grandchildren.