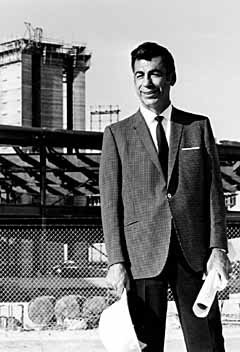

Kirk Kerkorian

Kirk Kerkorian, father of the Las Vegas megaresort, dropped out of school in the eighth grade to become a professional boxer, flew suicide missions for the Royal Air Force, made a small fortune in surplus military airplanes, and a larger one in the airline business.

In Las Vegas, he built three hotels that were the largest in the world in their time, and proved that, contrary to the wisdom of the day, courting the convention and family travel markets could be profitable.

Today, Kerkorian is the 41st richest man in the country, worth about $5.7 billion.

Kerkorian rarely attends board meetings and never gives speeches. He is shy, but a tough negotiator.

Those who know him describe him not as Hughesian hermit, but a gentle, gracious, normal guy.

“I’m far from being reclusive,” declares Kerkorian. “I have 30- or 40-year friendships that I prefer to meeting new people. I go to an occasional party, but just because I don’t go to a lot of events, and I’m not out in public all the time doesn’t mean I’m anti-social or a recluse. I’m at a restaurant three or four nights a week, here or in Las Vegas.”

His dark, motionless eyes are set below thick salt-and-pepper eyebrows. The tanned, deeply lined poker face reveals nothing. He may be amused, bored, or about to knock his interviewer through the second-story window of his Beverly Hills, Calif., office. He still looks capable of demonstrating why he was called “Rifle Right Kerkorian” in the boxing ring.

Kerkor Kerkorian was born in Fresno, Calif., on June 6, 1917, youngest of Ahron and Lily Kerkorian’s four children.

When the recession of 1921-22 wiped out the family, the Kerkorians moved to Los Angeles.

“Our first language, although we were born here, was Armenian,” Kerkorian recalls. “We didn’t learn the English language until we hit the streets.”

He sold newspapers and hustled odd jobs.

“When you’re a self-made man you start very early in life,” he says. “In my case it was at 9 years old when I started bringing income into the family. You get a drive that’s a little different, maybe a little stronger, than somebody who inherited.”

The Kerkorians moved often, and Kirk was always the new kid in school, obliged to prove himself. Big brother Nish, a pro boxer, coached him. By junior high school, he had been transferred to a disciplinary campus where order was maintained with a metal-studded leather belt. There were more fights than ever.

Kerkorian became the Pacific amateur welterweight champion and wanted to box professionally. He might have boxed himself into addled obscurity. Instead, he met Ted O’Flaherty.

In the autumn of 1939, Kerkorian was earning 45 cents an hour helping O’Flaherty install wall furnaces. Some days, Kerkorian would go with him to Alhambra Airport and watch him practice maneuvers in a Piper Cub. Originally disinterested, Kerkorian consented one day to go aloft with O’Flaherty.

As the plane rose, and the Southern California landscape became visible from the mountains to the ocean, Kerkorian experienced a defining moment.

“He was sold on it right then,” O’Flaherty later recalled. “He had never been up in a plane before. But I’m telling you, after that first flight he went right at it. The very next day, he was back out at the field to take his first flying lesson.”

With war clouds darkening Europe, he worried that he would be drafted into the infantry before he became a licensed pilot.

One day in 1940 Kerkorian showed up at the Happy Bottom Ranch in the Mojave Desert adjacent to Muroc Field, now Edwards Air Force Base. Owned by Florence “Pancho” Barnes, a pioneer female aviator, the ranch was a combination flight school and dairy farm.

“I haven’t got any money,” Kerkorian told Barnes. “I haven’t got any education. I want to learn to fly. I don’t know how I can do it. Can you help me?”

No college was needed, just the willingness to pull teats and shovel bovine backwash. Within six months, Kerkorian had a commercial pilot’s license, and a job as a flight instructor.

But teaching bored him.

“I heard about the Royal Air Force flying out of Montreal, Canada, and I went up there and I got hired right away,” he recalls. “They were paying money I couldn’t believe, $1,000 a trip.”

The mission of the RAF Air Transport Command was to fly Canadian-built Mosquito bombers from Labrador to Scotland. Only one in four made it.

The Mosquito’s fuel tanks carried it 1,400 miles. It was 2,200 miles to Scotland. Pilots had only two possible routes, each worse than the other.

The roundabout route was Montreal-Labrador-Greenland-Iceland-Scotland, but the planes’ high-performance wings could be distorted by a paper-thin coating of ice, causing it to fall out of the sky. “The snowfields and forests around that frozen perimeter were strewn with downed Mosquitos crushed like matchboxes,” wrote Dial Torgerson in the 1974 biography “Kerkorian, An American Success Story.”

Or one could fly straight across the Atlantic, riding a west-to-east airflow called the “Iceland Wave.” It blew Mosquitos toward Europe at jet speeds, but it wasn’t constant. If it waned in midflight, plane and pilot were lost.

Kerkorian and his wing commander, J.D. Woolridge, rode the wave in May 1944, and broke the old crossing record. Woolridge got to Scotland in six hours, 46 minutes; Kerkorian, in seven hours, nine minutes. He came in second. He hated that.

The following month, the Iceland Wave died halfway across. The sun set. The reserve tank ran empty, and Kerkorian prepared to ditch. His navigator begged Kerkorian to drop low just once. As they broke through the cloud, the lights of Prestwick, Scotland, twinkled ahead.

Kerkorian made a perfect landing.

In 2 1/2 years with the RAF, Kerkorian delivered 33 planes, logged thousands of hours, traveled to four continents and flew his first four-engine plane. He also saved most of his generous salary.

Kerkorian clearly recalls his first visit to Las Vegas in July 1945. His RAF service completed, he paid $5,000 for a single-engine Cessna in which to train pilots. “And I used that same plane to fly charters. That’s what got me into the transportation end of the business.”

Jerry Williams, a Los Angeles scrap iron dealer, hired Kerkorian’s plane two or three times a week to fly to Las Vegas. “I was just overwhelmed at the level of excitement in this little town,” he says. “The best times of my life were in Las Vegas.” One morning, Kerkorian and Williams emerged into the dawn after a fruitless night at the tables. They had $5 between them, and Williams suggested they save it for breakfast.

“What good’s five dollars going to do?” asked Kerkorian, and headed back to the craps table, where he won $700.

Kerkorian became well known as a high roller in Las Vegas during the 1940s and 1950s, “the Perry Como of the craps table,” for the unruffled way he could win, or more often lose, $50,000 to $80,000 per night. He eventually quit gambling entirely.

Married twice, Kerkorian met his second wife in Las Vegas. She was Jean Maree Hardy, a former dancer at the Thunderbird. The marriage produced Kerkorian’s two daughters, Tracy and Linda. Kerkorian named his personal holding company Tracinda Corp.

In 1947, Kerkorian purchased a tiny charter line, Los Angeles Air Service. He later changed the name to Trans International Airlines, and offered the first jet service on a nonscheduled airline.

In 1965, Kerkorian took TIA public. Armenian-Americans knew of Kerkorian and bought his stock. It rose from a low of $9.75 to a high of $32.

“It brought the stock up to begin with, and then our earnings were great, too, and it kept going up until we sold to TransAmerica,” says Kerkorian. In that 1968 deal, Kerkorian received about $85 million worth of stock in the TransAmerica conglomerate, making him its biggest shareholder.

In 1962, Kerkorian pulled off what Fortune magazine called “one of the most successful land speculations in Las Vegas’ history.” He bought 80 acres across the Strip from the Flamingo for $960,000. The price was low even then, and for good reason. A narrow band of property cut the 80 acres off from the Strip.

“It was landlocked,” says Kerkorian, “We traded the owners four or five acres for all of this thin strip that they could never build on. Then I got a call from Jay Sarno, and that’s how Caesars Palace got started.”

Kerkorian collected $4 million in rent before selling the land to Caesars for another $5 million in 1968.

With the cash from the Caesars sale and his TransAmerica stock, Kerkorian was ready to build his first Las Vegas megaresort.

In early 1967, he had bought 82 acres on Paradise Road for $5 million and hired Fred Benninger.

“All I knew about Las Vegas came from the other side of the table — the contributing end,” Benninger recalled years later.

“I’m not a firm believer,” says Kerkorian, “that you have to have 30 years of experience, if you’ve got good, common sense. I knew he could cut the mustard and he did. He helped, no, he built the International. He built the old MGM and he built this MGM. It was all Fred Benninger.

“I can’t take much credit except for seeing the big picture; the amount of rooms, what kind of showrooms, I’m into that part of it. But when you get the nitty-gritty, I don’t have the education to really get in there and dissect it.”

Benninger suggested that given the size of the International, they should buy an existing hotel, and use it to train staff. The Flamingo Hotel fit the bill.

Benninger installed Sahara Hotel Vice President Alex Shoofey as Flamingo president. Shoofey then stole the cream of the Sahara’s executives — a total of 33 — including casino manager James Newman and veteran entertainment director Bill Miller.

In February 1969, Kerkorian’s International Leisure was given the go-ahead by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission to offer the public about 17 percent of the company’s stock at $5 per share. This was not a routine approval, though. The Justice Department was investigating the Flamingo’s previous owners.

Justice Department officials had identified Meyer Lansky, Bugsy Siegel’s old partner in Murder Inc., as a hidden partner in the Flamingo. Skimming was suspected, and Kerkorian more or less proved it.

“The reason, I think, that they allowed us to go public,” says Kerkorian, “was that I don’t think the Flamingo ever showed anything more than $300,000 or $400,000 in profits. In our first year, 1968, we showed about $3 million.”

The location Kerkorian chose for the International was criticized. It was off the Strip and, at 30 stories and 1,512 rooms, the biggest hotel in the world. Too big and too far out, they said.

“We had the same doomsday people when we were building the MGM Grand, same people, same doomsday,” sighs Kerkorian. “You have to ask a lot of questions and listen to people, but eventually, you have to go by your own instincts.”

The International had a “Youth Hostel,” where kids could play and swim while their parents were doing grown-up stuff. The hostel organized field trips for the kids to Lake Mead, Mount Charleston and other local nongaming attractions.

“And that was before anybody’s time,” reminds Kerkorian.

“We opened that hotel with Barbra Streisand in the main showroom,” says Kerkorian. “The rock musical ‘Hair’ was in the other showroom and the opening lounge act was Ike and Tina Turner. Elvis followed Barbra in the main showroom. I don’t know of any hotel that went that big on entertainment.”

One month before the hotel opened, International Leisure common stock, which had opened at $5 per share, was selling over the counter for $50. But Kerkorian had some expensive European loans to pay off. He was confident he could retire them with a second offering of International Leisure stock.

The SEC refused to allow the sale on the grounds that Kerkorian had failed to disclose financial information about the Flamingo’s previous owners. Kerkorian’s people believe this information was not important to the SEC, but to a Justice Department investigation. “They employed a form of economic blackmail to try and get information out of us,” said a Kerkorian lawyer.

To pay off his debts, Kerkorian was forced to sell half of his own shares in International Leisure to Hilton Hotels. He got $16.5 million for stock worth $180 million only six months earlier.

Despite this, Kerkorian said he was proud of what he and his people had created in Las Vegas, and had no regrets. He sold his Las Vegas home, his private plane and his yacht. Colleagues were amazed at his calm during this time. But he had learned to always “keep a back door open.” To Kerkorian, that means it’s acceptable to lose most of what you have, as long as you can raise seed money for another enterprise.

At the same time he was making his splash in Las Vegas, Kerkorian was studying the Hollywood film industry and, in 1969 began buying stock in ailing MGM studios. By the end of the year, he would have working control of MGM, which he would operate, reorganize, merge, sell and resell over the years. Most recently, he repurchased MGM/UA in 1996.

He was at the helm in 1971, less than a year after the sale of the International, when MGM announced it would “embark on a significant and far-reaching diversification into the leisure field by building … the world’s largest resort hotel in Las Vegas.” Now known as Bally’s, it was originally known as the MGM Grand. Today’s MGM Grand is a different property.

At its 1972 groundbreaking ceremony champagne flowed, celebrities mingled, and executives networked. In a corner, nursing a J&B Scotch and trying not to be noticed, was the man whose project was being celebrated.

The new $107 million megaresort was named for a 1932 MGM film, “Grand Hotel.” At 26 stories, the MGM Grand had 2,084 rooms, a 1,200-seat showroom and amenities like a shopping arcade, movie theater and jai alai fronton.

When it opened July 5, 1973, it was the largest hotel in the world — just as the International had been. Some saw a pattern developing, but Kerkorian denies he has ever built a hotel just for the sake of size. His hotels, he explains, are built on a grand scale to house a variety of diversions for guests.

The biggest hotel in Las Vegas was the site of the city’s biggest disaster in November 1980, when a fire, ignited by an electrical problem, raged through the casino and upper floors of the MGM, killing 85 and injuring hundreds.

The great poker face softens and the brown eyes lower when the catastrophe is mentioned.

“It’s something I rarely ever talk about, because how do you talk about it?” he says quietly. “I was in New York in a meeting with people from Columbia Studios, and I had an emergency call telling me that the hotel was on television, on fire, and in less than two hours I was at the airport and on my way to Las Vegas.

“The two people I really felt for at the time were Fred Benninger and Al Benedict, because they were on the front lines through everything that happened.” Benedict was hotel president.

Benedict later told Review-Journal reporter Dave Palermo that when Kerkorian arrived a few hours after the blaze, his first question was, “Where do we start?”

“I figured there was no way we could come out of this.” said Benedict. “I think the idea of walking away and forgetting about rebuilding the property was in the back of everybody’s mind. That’s what most people would have done.”

But not Kerkorian. Eight months later, the MGM Grand re-opened.

“How could I walk away while that whole team was out there, taking the brunt from everybody? I had to be a part of it, I couldn’t walk away, I just couldn’t.” In 1986, he sold the Las Vegas and Reno MGMs to Bally Manufacturing Corp. for $594 million.

The current MGM Grand, which opened in 1993, has 5,000 rooms, eight restaurants, a health club, a monorail, the 15,000-seat MGM Grand Garden and a theme park as big as Disneyland when it opened in 1955.

As for the health of the Las Vegas resort industry, Kerkorian remains as bullish as he was back in 1945.

“Personally, I wouldn’t say it’s headed for a fall,” says Kerkorian, “except that there will be a leveling-out time, and the best hotels and the best operators are going to suffer less than the others.”