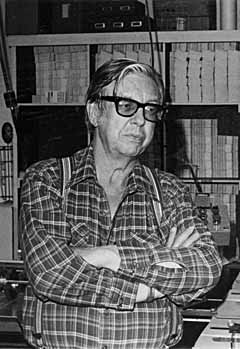

John Luckman

In one corner of the Gambler’s Book Club an old couple in straw hats and fanny packs scan a large array of volumes on winning at video poker. A couple of sweaty fat guys festooned in gold neck chains are engaged in animated debate over horse betting. An intense-looking young man with thick glasses pores over a thick book on higher mathematics in gambling. A video on a wall-mounted television set blares step-by-step instructions on pai gow poker.

It’s lively out front, more so in back, where telephone and mail orders are being sent out as fast as they are placed. The Gamblers Book Club is far and away the world’s largest supplier of books on gaming, magic, the mob and Las Vegas in general. It is a unique enterprise, conceived by a unique man.

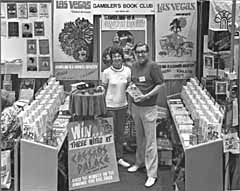

He was John Luckman, co-proprietor with his wife, Edna, of the Gambler’s Book Club. He also was an author and publisher, literally the creator of a whole new genre of instructional literature, nearly all of it aimed at creating better-informed players.

Edna Luckman is now in her 35th year as the company’s bookkeeper. She, along with store managers Howard Schwartz and Peter Ruchman, are today the fierce guardians of Luckman’s legacy.

The Gambler’s Book Shop at 630 S. 11th St., the club’s retail outlet and headquarters, is as much a school as a store. The person behind the counter will probably be a seasoned dealer or player, freely dispensing advice and words of caution.

“We’re kind of like Consumer Reports for gamblers,” says Ruchman, a blackjack player who came to Las Vegas in the 1960s. The Gambler’s Book Club banks on its reputation for honesty and integrity, a reputation built by the founders.

“John and Edna were both straight as arrows,” says Ruchman. “When they went into a casino to eat, they would go through the back door, so no one would notice them and hit them with a comp. After they were done eating, and paying for their own meals, they would go out into the casino, say hello to everyone and play. They did not want to be compromised or beholden to anyone. Look at any of our literature for 35 years, there’s not a single advertisement for any product.”

John Lester Luckman was born in Oak Park, Ill., Sept. 24, 1928. He served in the Marine Corps during World War II but saw no action. Discharge found him in Santa Monica, Calif., working as a pinsetter in a bowling alley. It was there that he met a lady accountant named Edna. They were married in 1946, and had no children.

The bowling alley was a daily stop for a local bookie, and Luckman would occasionally lay a bet.

“But after awhile,” his widow recalls, “he realized it was the bookmaker who had the big bankroll. So he went to work for him.”

The couple owned a carpet store for a time, and also made periodic pleasure trips to Las Vegas. In 1955, a police crackdown on bookmaking prompted the Luckmans to move to Las Vegas permanently.

Luckman wanted to work in the casino industry, and was willing to start at the bottom. He graduated from a storefront “dealer’s school,” and was eventually hired by the Pioneer Club. He also worked at the Mint, Caesars Palace and the Tropicana. A voracious reader, Luckman tried to climb the ladder of success through self-education, and was amazed to discover that there were a grand total of 18 gambling books in print. So he began to seek out and collect used copies of out-of-print books.

Edna Luckman remembers that people were always borrowing from her husband’s one-of-a-kind collection, and he began to suspect that there was an unfulfilled need for more and better information on gaming.

His observations of players’ habits convinced him.

“He could see that people had no idea what they were doing,” says Edna. “They didn’t even get a run for their money.” And players had no monopoly on gambling ignorance, he decided.

“John believed that many of the people in casino management don’t understand the games they’re in charge of,” says Schwartz. “He used to call them ‘lumpies’ as in lumps. They were juiced in; someone’s relative or friend.”

By 1964 the Luckmans were convinced that there was indeed a market for gambling texts, and the Gambler’s Book Club was born. The name was significant, says Schwartz, because Luckman envisioned not just a bookstore, but a library of gaming, and a forum for gamblers to gather and visit, argue, gossip, lie and, most of all, learn from each other.

Luckman’s first priority was crafting primers for greenhorn gamblers.

Under the pen name Walter I. Nolan (WIN), he wrote a series of little paperback books that explained the basics of a particular game, such as “The Facts of Blackjack,” and “The Facts of Craps.”

The Luckmans produced the books at home. A neighbor, an official in the Mormon Church, had a broken reproduction machine that Luckman repaired in exchange for its use. The books were sold by mail order and in casino gift shops. Some bosses grumbled about wising up the suckers, but sales of the 50-cent books soared, and they remain among the most popular titles Luckman ever published.

“At the very height of their popularity,” says Schwartz, “the `Facts of …’ series was selling 1,500 to 5,000 copies a month.”

In 1968, John and Edna resigned from their jobs at the Tropicana and Pioneer Club, respectively, and went into the book business full time. Their first store was at the corner of Charleston Boulevard and Main Street. A vacant wholesale grocery building, a block off east Charleston, later became the current headquarters.

The lack of titles with which to stock the store and the catalog was a problem, one that Luckman solved by expanding the publishing business. The copyrights had long expired on most of the old books Luckman had collected, so anyone had the right to reprint them. Luckman pounced on them, running off a few hundred at a time.

“He resuscitated a lot of old classics,” says Schwartz. The first was a reprint of the 1908 “Racing Maxims & Methods of Pittsburgh Phil,” which was based on the only interview ever given by the legendary horse-player. Another was “The Stealing Machine,” written in 1906 by French detective Eugene Villiod. It explains complex cheating and bunko schemes, some still in use today.

He also published the debut books of David Sklansky, “Winning Poker” and “Hold ‘Em Poker,” still among the hottest titles in the store. Frank Scoblete and John Patrick published their own first books, but the Luckmans introduced them to the public; all three are now successful gaming authors.

Ed Silberstang was already one of the country’s best-established gambling authors, with his classic “Playboy’s Book of Games.” But Luckman published some of Silberstang’s works on uncommon games, which had audiences too small for major publishers. They became fast friends. “He ran a bookstore for writers and he had respect for writers,” said Silberstang. “I met a lot of other writers through him. If he knew two people who had something in common, he would find a way to introduce you.”

Luckman realized very early that many real gaming wizards had no literary inclination. If he wanted their expertise reduced to print, he would have to be an editor, too.

“Many of our best books were spoken directly into a tape recorder, then transcribed and edited,” says Schwartz. Some very advanced books, involving higher mathematics, were penned anonymously by high-minded college professors who were closet gamblers.

In 1979, Luckman hired Schwartz, a journalist, to edit the store’s two magazines, “Casino and Sports,” and “Systems and Methods.” The latter was concerned with pari-mutuel betting on horses or dogs. Naturally, all new gambling books were reviewed.

“Half of the magazine was devoted to analyzing gambling systems,” says Schwartz. He explains that these “systems,” touted as being the pathway to riches, are usually some sort of scam or a rehash of common knowledge, with a hefty price tag attached.

Luckman took particular pleasure in exposing bad books and systems, and endorsing those that were sound. He saw no reason why his favorite form of recreation should be associated with flimflammery.

“John tried to convince everybody that gambling was adult recreation,” says Edna Luckman. “You’re not going to retire on it. Just know what you’re doing and have some fun.”

In the mid-1980s, Luckman’s health began to fail. Magazine and book publishing ceased in order for the staff to concentrate on its lifeblood publication, the mail-order catalogue.

In early November 1987, Luckman died of a heart attack brought on by kidney failure. Schwartz and later, Ruchman, became what they describe as “the keepers” of his legacy.

“Our business used to about 70 percent walk-in, and 30 percent mail order,” says Schwartz. “Now, it’s almost reversed.” One reason, he says, is the proliferation of legalized gambling overseas, especially in Australia and the Pacific Rim. Foreign orders now account for about 20 percent of the mail-order trade.

Schwartz and Ruchman seem to have preserved the sterling reputation Luckman nurtured — that is, if the caliber of the store’s patrons are any indicator.

“Douglas Dunlap, FBI Special Agent, just called last Tuesday, and had me Federal Express him 1,000 catalogs,” says Ruchman. “He needed them to re-supply his field agents.”

Part III: A City In Full