Jerry Vallen

I believe in matches,” says Dr. Jerry Vallen, dean emeritus of the UNLV College of Hotel Administration. He isn’t talking about the wooden kind, but the circumstances under which he founded and built the UNLV hospitality program into the largest at the university and one of the most respected in the world.

It was the summer of 1967. The 12-year-old college, then called Nevada Southern University, was planning to start a hotel college, then a tiny division of the College of Business and Economics. There were 18 students enrolled, no laboratory or equipment and a faculty made up mostly of volunteers from local hotels. On the other hand, there was an enthusiastic local resort association, ready and willing to bankroll the start-up, lend employees to serve as faculty, and allow their properties to be used as laboratories. And there was a rapidly growing city and university in need of an institution that would train future managers and executives.

Vallen saw a match. Not all the teachers and administrators who came to Las Vegas to interview shared Vallen’s vision.

Longtime Las Vegas casino executive Leo Lewis recalls that some candidates cut and ran when they got a look at “Tumbleweed Tech.”

“Nobody wanted to come out to the desert,” Lewis says. “People didn’t want to come to a brand-new school with no reputation and very few research or library facilities.”

So, while the ivory-tower types saw a primitive facility in a low-brow town, Vallen, whose background included nearly as much work experience as classroom time, saw that if the school were to flourish, it would have to maintain strong ties to the city’s lifeblood industry. This was no problem. He spoke their language.

In 1979 a reporter asked Vallen if he wanted an on-campus hotel to train students.

“Why do we need a hotel here?” he laughed. “All we have to do is call on our friends.”

Jerome J. Vallen was born in Philadelphia in 1928, one of three sons of a restaurateur who owned four restaurants and wanted each of his three sons to inherit one. All the boys worked in the family eateries, and understood the business before graduating high school.

Young Vallen was interested in restaurants, but more interested in education, so his father sent him to Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. He graduated in 1950 with a bachelor’s degree in hotel administration, and a plan to teach that discipline. That same year, he married Florence “Flossie” Levinson. The couple had four children, one of whom, Gary, followed in his father’s footsteps and is a professor in the hotel college at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff.

Between 1950 and 1959, Vallen worked toward a master’s degree in educational administration from St. Lawrence University, skipping a semester here and there to take hotel management jobs in Atlantic City, Philadelphia and Miami, and at resorts in New Hampshire and upstate New York. It would be 1976 before he earned his Ph.D. in hotel administration from Cornell.

In 1953, he joined the faculty of the department of food service and hotel management at the junior college of the State University of New York.

“I learned from my experience at SUNY,” Vallen recalls, “that we had a whole bunch of really qualified kids who wanted to go on to a four-year program, but nobody would take them. They didn’t have enough space.”

Vallen explains that in 1922, Cornell University launched the nation’s first four-year degree program in hotel management. By 1967, there still were only 10 major universities offering the bachelor’s degree in the hospitality field, and the demand for graduates with degrees far exceeded the supply. Numerous junior colleges offered two-year hotel management programs, but space in four-year programs was limited. One reason for the dearth of baccalaureate programs is that they tend to be equipment-intensive. Expensive laboratory kitchens, faux front desks and a lot of specialized classroom space must be dedicated to the exclusive use of the hotel college.

In 1966, the Nevada Resort Association offered to take the lead in establishing a hotel school at Nevada Southern. The NRA appointed Leo Lewis, then a casino executive with Binion’s Horseshoe Club, as well as Phil Arce from the Sahara and Frank Watts from the Riviera. They were to work with university President Donald Moyer and Richard Strahlem, acting dean of the fledgling school, to recruit a faculty and dean and get a program started.

The NRA also agreed to finance the start-up to the tune of $280,000 over four years. It was that commitment, and the warm welcome he received in 1967 from association members, says Vallen, that convinced him he had the right “match” to create a first-rate hotel school. He was joined that same year by Boyce Phillips, the second founding faculty member.

The cozy relationship between the university and the resort industry raised eyebrows back then, and still does today.

“Casinos reign supreme,” wrote Review-Journal education columnist Ken Ward recently. “UNLV’s professoriate is a collective apologist for the gaming industry.”

Vallen replies that if the casino boys were calling the shots behind the scenes, he failed to hear them. If there is a perception that the gaming curriculum taught at the UNLV College of Hotel Administration was a condition of the hotel industry’s support, it is false.

“It was my idea,” declares Vallen. “It was never one of the prerequisites set by the resort association; it was never even mentioned. As we began to grow, I began to think of ways we could market ourselves differently from the other hotel schools in the country. The answer was right here.”

One of the early courses set off alarms with gaming regulators in Carson City. It was titled “protection of the games.” It was designed to train dealers in how to spot players cheating. But an official at the Nevada Gaming Control Board was suspicious, and called Vallen.

“You can’t teach people how to cheat,” he said. Vallen agreed.

Nor did he operate a dealer’s school.

“We don’t teach how to deal cards, fix slot machines or make change in our classes,” Vallen said in 1979. “If our students need experience in that area, they can get it in the hotels. Instead, we discuss the various management systems used in casinos. We teach accounting, marketing, internal gaming control, the impact of new legislation on gaming and how the changing odds will affect the hotel’s revenue.”

Vallen points out that without the NRA’s initial help, it is unlikely the school would exist today.

“It was a lucky thing we weren’t supported by public funds.” he says. “I had only 18 students and it would have been hard to to justify asking state lawmakers for money for such a small program. The association money enabled us to start up classes without having to go to anyone else for funds.”

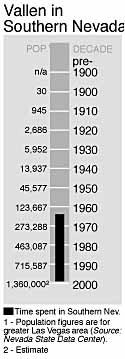

By 1971, the University Board of Regents split the business and hotel schools. The hotel school was given its own budget. Vallen was officially named dean of the new, rapidly growing college. From a student body of 18 in 1967, enrollment rose to 120 the following year. In the early 1980s, the Legislature approved $10.8 million for Frank and Estella Beam Hall, completed in late 1982. It would house the business school and the college of hotel administration. Just in time, too. By 1979, enrollment had risen to 790 students. Today, enrollment is about 1,800.

“When we opened the program here, what I did was recruit from the junior colleges, of which there were about 200 around the United States,” says Vallen. “That’s why our enrollment just skyrocketed. I decided to service a market that no one else would touch.”

The backbone of Vallen’s academic program is the internship, something not offered at even the best hotel schools.

“I told the resort association that if they’re going to be with us, we want internships,” says Vallen. And he got internships — after he and President Moyer met with Al Bramlet, secretary-treasurer of Culinary Workers Local 226, to assure him the program would not displace workers.

UNLV hotel students must take not one, but two internships. In the first, the freshman or sophomore student must find a paying job, and hold it for 800 hours, or about two summers. For this, no academic credit is given.

“In the (second) internship, in their senior year, we find the job, they are not paid, and they get three academic credits,” says Vallen. Because his interns have quite a bit of experience by their senior year, as well as academic training, he easily places them in hotels around the world.

Attracted by the college’s reputation — and, no doubt, the city — international students are increasingly choosing to study hotel administration at UNLV.

“In a typical term,” says Vallen, “we would have students from 42 states of the union and 15 to 25 countries — Greece, Turkey, China, Israel, the Philippines. Practically everywhere.”

With success came money, and by the early 1990s, the hotel college was doling out over a quarter of a million dollars a year in scholarships. In 1988, the school received its biggest gift ever, a check for $5 million from Verna Harrah, widow of gaming pioneer William F. Harrah. In his honor, the college was renamed the Harrah College of Hotel Administration.

And while Vallen, who retired from UNLV this year, has been a master fund-raiser, he is lavish in his praise of hundreds of tourism professionals who have taught, lectured, made donations or offered a scholarship.

“I’ve never called anyone who failed to respond,” he says.

“And the industry has had a return on its investment many times over in the manpower supply that we presented to them.”

Part III: A City In Full