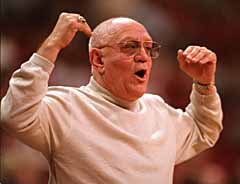

Jerry Tarkanian

Whatever fame UNLV enjoys nationally rests largely on its Jerry-built basketball program, as do negative aspects of the university’s reputation.

Through nearly two decades at UNLV, Jerry Tarkanian’s teams were under almost constant investigation or sanction by the NCAA. He in turn accused the NCAA of singling him out for harassment, and eventually won a large cash settlement, an unheard-of victory over the powerful collegiate athletic watchdog.

Most Las Vegans couldn’t have cared less what the National Collegiate Athletic Association thought of UNLV’s recruiting practices. They loved Tark the Shark and his teams. Their public image was a metaphor for Las Vegas: A little wicked, a little wild, and all but unbeatable.

Tark’s mother was a refugee from the genocide that killed more than 2 million Armenians over 24 years. In a 1988 autobiography, Tarkanian and his co-author, Terry Pluto, described without emotion the terrible event that sent his mother to America. Tark’s grandfather, Mickael Effendi Tarkhanian, was a government official. His oldest son, Mehran, was a medical student. Turkish militiamen arrested Effendi Tarkhanian and forced him to watch while they beheaded his son. Then the elder Tarkhanian was himself killed.

His widow, learning of their deaths, immediately sent her other young son, Levon, and one of her four daughters, Haigouhie, fleeing on horseback. As Haigouhie and Levon climbed a hill not far from town, they turned and saw soldiers forcing women and children into a church. Then the soldiers locked the doors and burned the church down.

Later, in Lebanon, Haigouhie married a man with a name similar to her father’s, and returned with him to the United States, where she was known as Rosie Tarkanian. Jerry was born in 1930.

He won an athletic scholarship to Fresno State University, but Fresno’s athletic program was dirt-poor in those days, so the scholarship was worth only $50 every three months. Tarkanian served as a personal aide to football coach Clark van Galder, one of the greatest influences on Tarkanian’s life.

“He was an extraordinarily intense individual, and he demanded equal intensity from his players,” Tarkanian wrote. “How he got it was by becoming close with them, by forging an emotional bond. He would take me and my roommate Fred Bistrick, Fresno’s quarterback, to the high school games with him. … We spent a lot of time with his family.”

Orthodox coaches in those days were compared to generals, goal-focused and aloof, so van Galder was a heretic. Tarkanian adopted the football coach’s creed and toted it over to the basketball gym. Tarkanian was too short and too slow for the first string, but had dedication and a gift for analyzing plays.

When his eligibility ran out, Tarkanian helped coach at a nearby high school. He proved so good he became head coach, in function if not in title, while still in college. He is one of the few college coaches who has never been an assistant. He coached at four high schools, then in 1961 was hired by Riverside Junior College, which hadn’t had a winning season in 11 years. Under Tarkanian, Riverside became the first team to win three consecutive state junior college championships. Moving to Pasadena City College in 1966, he converted another terrible team to state champions in his first year.

Meanwhile, he had married Lois Huter, who he had met while both were students at Fresno State. Lois became an educator and in Las Vegas was elected to the Clark County School Board.

The Tarkanians have four children. Danny would play on Tarkanian’s first string at UNLV, is currently one of his assistant coaches, and also has practiced law. George is head basketball coach at College of Sequoias in Visalia, Calif. Jodie Diamant is a nurse and homemaker. Pamela Tarkanian is a special education administrator in the Clark County School District.

In 1968, he was asked to repeat his team-building magic at four-year Long Beach State College. Most four-year coaches considered junior college players second-rate material, but they had helped Tarkanian build his name. He bragged that when he first took a team to the NCAA tournament (from Long Beach in 1970) the entire first-string consisted of former junior-college men.

However, his reliance on junior college men contained the seeds of controversy. “Soon Tarkanian’s approach provoked complaints that he was running a `renegade’ program built upon less than stellar students,” wrote Richard O. Davies, a University of Nevada, Reno history professor, in his book on controversial Nevadans, “The Maverick Spirit.”

Davies also notes Tarkanian was one of the first to ignore an unwritten rule that three of the five starting players had to be white. “This dramatic departure from racial convention established Tarkanian in the black community as a coach who not only talked about equal opportunity but actually practiced it. This reputation would pay great recruiting dividends later in his career.”

UNLV boosters in 1973 were not interested in the color of his players, either. They were interested in a coach who had put obscure Long Beach State College onto the map by winning 122 games, losing only 20, in five years.

When Dr. Donald Baepler, then UNLV’s academic vice president, hired Tarkanian, no one else was seriously considered.

Irwin Molasky, a wealthy businessman noted for supporting UNLV, said he wasn’t on the team that recruited Tarkanian but understood their thinking. “For us to become the Harvard of the West would take 50 to 100 years, but in a limited amount of time he got us a lot of recognition,” said Molasky.

His first season was 20-6.

Then famous for slow, methodical play, Tarkanian adopted an entirely new style at UNLV. His second season found him with guys who were short, by basketball standards, but could run like antelope. “I figured that if we got the bigger teams running, it would take away their size advantage,” he wrote with Pluto. “Rather than work the ball around the perimeter, I wanted us to get the ball up the court as fast as possible, and then take a quick jumper before the defense could set up. Speed would be the determining factor in the game. The team that got the rebounds would be the team that hustled for the ball more and reached it first,” and not necessarily the taller one.

This strategy also required using a man-to-man defense instead of the zone defense that was Tarkanian’s celebrated forte.

They lost the first three games they played that way, but came together in the fourth and finished the season 24-5. The Rebels became the Runnin’ Rebels.

Fans loved the new game. It had the energy of a high school game played with a lot more skill. Some said it looked like an NBA game. The 1975 team often scored more than 100 points a game and set a collegiate record of 164 points against Hawaii. It went to the NCAA tournament that year; in 1977 UNLV played in the semifinals, losing 84-83 to North Carolina.

Baepler, by then president of UNLV, said, “Prior to 1977 I had to explain at national meetings, `Yes, there is a university in Las Vegas.’ And after that they knew.”

Success meant being taken seriously in the Nevada Legislature, which had formerly treated UNLV as a stepchild to the “real” university at Reno. “Before we hired Jerry we had a dream of having a big facility like Thomas & Mack Center, and we knew we had to have a big program to get it,” said Baepler. “We thought Jerry could do that, and he did. The Las Vegas Convention Center, where UNLV played its games then, sold out. There was a big demand for tickets, and we were thus able to document the need for a bigger facility.”

Opening in December 1983, the Thomas & Mack brought UNLV’s most high-profile program onto the UNLV campus. The multipurpose arena became known as “The Shark Tank,” but it also would allow Las Vegas to host the National Finals Rodeo, as well as other events and concerts.

But storms move northeast in the Mojave Desert, and a big one followed Tarkanian from Long Beach. He claimed it started when he wrote a newspaper column criticizing the NCAA. “It’s a crime that Western Kentucky is on probation but the famous University of Kentucky isn’t even investigated,” he wrote. “The University of Kentucky basketball program breaks more rules in a day than Western Kentucky does in a year. The NCAA doesn’t want to take on the big boys.”

Very shortly the NCAA announced not only an investigation of his Long Beach program, but that it was reopening a dormant investigation of the UNLV program he had just agreed to head up.

In 1976, the NCAA charged UNLV with 10 major infractions of its rules, including one charge that Tarkanian had arranged for player David Vaughan to receive a “B” in a class without even attending it, had arranged for a player to get free clothing, and had arranged for players to travel free on airplanes chartered by casinos. Tarkanian expressed outrage at the grade-fixing charge, and also denied the clothing comp. Regarding the junkets, Tarkanian said that he pointed out to the junket operators that NCAA rules required the plane seats be available to other students as well as players, then provided his players with a telephone number for the operators.

UNLV conducted its own investigation but was unable to corroborate the charges. The NCAA found UNLV guilty of all charges anyway, and ordered Tarkanian removed from contact with the UNLV program for two years.

Tarkanian sued, and in October 1977 District Court Judge James Brennan granted a permanent injunction prohibiting the suspension.

NCAA investigator David Berst “threatened, coerced, promised immunity, promised rewards to athletes in his effort to obtain derogatory evidence against the plaintiff,” Brennan wrote.

Tarkanian had won, but it was only the first round.

Each succeeding year brought new allegations, some leveled by the NCAA, some by local media. Players driving luxury cars of cloudy title. Players involved in brawls and petty crimes.

One of the most infamous cases was the recruitment of Lloyd Daniels, a Brooklyn playground legend. A report by the Long Island Newsday said this alleged scholar was functionally illiterate, and had failed to get a high school degree from any of five high schools. (Tarkanian said Daniels was dyslexic, not illiterate.)

Somebody provided Daniels with a car, which was against NCAA rules; arrangements were made for him to live in Las Vegas rent-free. In what many considered an attempt to circumvent rules limiting the amount of contact coaching staff could spend grooming a prospect, assistant basketball coach Mark Warkentien became Daniels’ legal guardian.

In early 1987 Daniels was caught buying cocaine from an undercover police officer. The buy was actually videotaped by a local television station covering the sting operation.

Despite his reputation as “the Father Flanagan of college basketball,” Tarkanian then said there was such a thing as a boy too bad to play for UNLV, and Daniels was him.

Dr. Paul Burns, a retired UNLV history professor and administrator, was faculty athletics representative from 1985 to 1994, in charge of verifying the academic eligibility.

“It struck me as odd that he made some of his biggest mistakes when he was at the peak of his career, when he could have his pick of a lot of players,” said Burns. “Recruiting Lloyd Daniels and letting Mark Warkentien become his legal guardian; those things are beyond the pale.”

Never once, said Burns, did Tarkanian or his staff exert pressure to bend academic rules.

Enter Dr. Robert Maxson, a president recruited from the University of Houston in 1983 to do for UNLV’s academic reputation what Tarkanian had done for its athletic one. He did advance UNLV’s national academic image, but ultimately at the price of its most successful athletic program.

“You can’t assess Tarkanian without assessing Bob Maxson,” said Michael Green, a history professor at Community College of Southern Nevada. “To their mutual chagrin, they are historically inseparable. … They became embroiled in this terrible fight where neither man controlled his logic or emotion. In a sense, they destroyed each other. The fight also divided the town, and I think the town is still divided.”

Maxson tried, initially, to make Tarkanian an ally, escorting important guests to UNLV basketball games, particularly in the 1989-90 season, which culminated in UNLV’s first NCAA championship. When an NCAA ban on post-season play effectively prohibited the champions from defending their title — Maxson helped work out a compromise that delayed the ban until 1992.

The relationship quickly soured, particularly after 1990 when Maxson forced the resignation of Brad Rothermel, the most successful athletic director UNLV ever had, and replaced him with Dennis Finfrock, no fan of Tarkanian. Rothermel later told a committee of the Nevada Legislature, investigating the Maxson-Tarkanian feud, that Maxson asked him soon after arriving at UNLV whether he had evidence that could be used to fire Tarkanian.

The reports that most disturbed Maxson said Richard Perry, a New York gambler who had been convicted in the Boston College basketball point-shaving scandal, was hanging around the UNLV program. It turned out Perry had helped UNLV land the ill-starred recruit, Daniels. Close association with any gambler was prohibited by NCAA rules. Hanging out with a Mafia associate famous for fixing basketball games looked infinitely worse.

Tarkanian said he initially knew Perry only as a summer league coach who spotted great unknown talents. Once Perry was identified as the infamous “Richie The Fixer,” Tarkanian said, he warned his players to stay keep away from Perry, and did so himself.

The 1990-91 team produced the finest record UNLV ever had, 34-0, then lost 79-77 to Duke in the 1991 NCAA semifinals. Duke was the team that UNLV had eaten alive in the 1990 championship, scoring 103-73.

On May 26, 1991, the Review-Journal published photos of Perry sharing his backyard hot tub, and playing basketball on his backyard court, with three members of the 1990 championship team. The photos were believed to have been taken in the fall of 1989, months after Tarkanian told his players to stay away from Perry. One of the three, Anderson Hunt, subsequently admitted visiting Perry’s home sometime after the 1990 championship, along with another UNLV player he didn’t identify.

On June 7, Tarkanian resigned. His attorneys had worked out an agreement that he would be allowed to coach the team one more year, when it would be banned from post-season play in any case.

Although the FBI issued a curious statement that “neither the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, nor its present or former basketball players are subjects or targets of a point-shaving investigation,” at least four people were questioned by FBI agents about Perry’s relationship to the team, or whether points might have been shaved. Nothing came of that investigation, but Perry subsequently was added to Nevada’s “Black Book” of people who are not allowed in any gambling establishment.

The 1991-92 Rebels, playing for pride instead of the playoffs, delivered 26 victories and lost but twice. Tark’s last game for UNLV, on March 3, 1992, was a 65-53 victory over Utah State. The Review-Journal headline next morning said: “Tark goes out a winner.”

Maxson was gone two years later. In the spring of 1994 he became president of Long Beach State — the other four-year college Tarkanian had put on the map.

After leaving UNLV in 1992, Tarkanian coached the San Antonio Spurs briefly, didn’t get along with the owner, and got fired.

He resumed college coaching at Fresno State. Meanwhile, he used a $1.3 million settlement from the Spurs to fund a lawsuit against the NCAA.

In April 1998, the NCAA announced it was paying $2.5 million to Tarkanian. It never quite admitted harassing Tarkanian, but vowed “some improvements in the enforcement process …”

To Tarkanian and those who believed in him, it sounded like vindication.