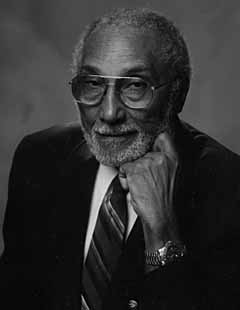

James B. McMillan

James B. McMillan was about 5 when he saw the Ku Klux Klan horsewhip his mother.

It was supposed to deter any other blacks who might be tempted to stand up for themselves. But McMillan was not deterred. He got angry and stayed that way long enough to overturn the Jim Crow policies that once earned Las Vegas the name “The Mississippi of the West.”

McMillan, a Las Vegas dentist and former president of the local NAACP, was born in 1917 in the actual Mississippi, where the whipping occurred.

McMillan explained that his ex-slave grandmother had three children by a white veterinarian. Interracial marriage was prohibited in Mississippi, but because a veterinarian was important in a rural community, his mixed-blood family was never mistreated. That changed suddenly after the veterinarian grew old, blind and less important.

The vet also had a daughter by marriage to a white woman. This daughter resembled McMillan’s light-skinned mother, Rosalie McMillan, and these half-sisters were friendly with one another. One day Rosalie was in a downtown five-and-dime where her half-sister worked. The white woman’s boyfriend walked in, mistook Rosalie for his girl, covered her eyes from behind and yelled, “Guess who?”

“She turned and slapped him,” related McMillan in an interview in January 1999. “He got mad but apologized. Her half-sister got mad, and yelled, ‘That’s my nigger sister!’ And my mother raised so much hell that the Klan came.”

The Klan butted into a private misunderstanding to “discipline” Rosalie for raising her hand and voice to whites. Masked men went to her home a day or two later and hauled Rosalie downtown. There they tore off her blouse and lashed her bare back 15 times with a buggy whip. “From the front porch of our house on the hill I could look down and see this,” remembered McMillan in his 1997 autobiography. “But there was nothing I could do and I just cried.”

Not long after, Rosalie and her family were driving across a wooden bridge and found a black man dangling in a noose. “My mother put the whip to the buggy, and we went on home,” said McMillan. “My recollection is we left Mississippi the next week.”

The McMillan book was written with the help of Gary E. Elliott, a history teacher at Community College of Southern Nevada, and R.T. King, director of the oral history program at the University of Nevada, Reno. They called it “Fighting Back,” because it is primarily concerned with McMillan’s lifelong struggle against racism.

McMillan grew up in New York City, Philadelphia, Pontiac and Detroit. His father died in the Spanish flu epidemic when McMillan was an infant. His mother eventually married a man with the knack of making money — in concrete, until the Depression crushed construction, and thereafter operating an illegal numbers game.

McMillan said ghetto schools didn’t teach him much science or literature, but he did learn to deal with bullies. “One guy pushed me around a whole semester. He’d run up when I wasn’t looking and jump on me and knock me down. So something said to me, I have to fight him. The day I made up my mind to fight him, I saw him out of the corner of my eye, he started running at me. I flipped him over my back onto the ground and kicked him in the head. He started crying. … And he and I were friends after that, all the way through high school.”

McMillan was the only black player on the University of Detroit football team. Teammates accepted him, but in his junior year the school administration kicked him off the team and revoked his athletic scholarship for dating a white girl. He paid for the rest of his education by working in an auto factory.

He entered dental school in 1941. When World War II broke out McMillan and many other dental students were deferred from active duty. After graduation in 1944 he practiced dentistry in the U.S. Army, and rose to the rank of captain.

He was also arrested for refusing to move to the back of an Army bus and getting into a fight with the driver who tried to throw him off. But his one night in the brig resulted in victory. The base commander brought the whole camp to attention and announced: “As long as I am in command here, this type of thing will not happen. There will be no difference in races.” McMillan served again during the Korean War, after the services were integrated.

He set up private practice in Detroit, and became friends with Dr. Charles West, a black medical doctor in the same neighborhood. West married a showgirl and began commuting to the West Coast, where his new wife was working, and once happened to take an alternate route through Las Vegas. “He liked the weather, the nightlife and the gambling,” said McMillan, so West settled here.

Not long after, McMillan went to the office on a winter morning. “We had those window units, combination of heaters and air conditioners, and they weren’t working, and it was just miserable. … I called Dr. West and asked him what the temperature was in Las Vegas and he said 75 degrees. I said, ‘I’ll be out this week.’ ”

On arriving in Las Vegas, he asked the cab driver to take him to Dr. West’s office at 524 Wyatt Ave. The driver was unfamiliar with the address and radioed his dispatcher for directions. “That’s over where them niggers live,” squawked the radio. The driver apologized and delivered McMillan to West’s office.

So when McMillan moved here in 1955, he expected a cool reception, and was not surprised. Even after he passed his Nevada dental examination with high grades, it took months for the board of dental examiners to license him. Dr. Quannah McCall, a board member who was an American Indian, cut the red tape. Approval of a license required a unanimous vote, and some were were dead set against approving a black dentist, McCall later related to McMillan. “I told them that if they didn’t pass you, nobody else would pass as long as I was on the board,” McCall said, so McMillan got his license.

There was a dental association, which didn’t welcome its new member. The dental wives’ club disbanded rather than welcome his new spouse. “You couldn’t live in the best places. There was disrespect everywhere.”

But there were already people working to end it. “David Hoggard, Woodrow Wilson, Lubertha Johnson and a couple of preachers were here before I got here and were working tremendously hard.

“Hoggard was on the police force, and he was a truant officer, and had good contacts with most politicians. He would try that way to get things done.

“Mrs. Johnson had a grocery store, and she would hire blacks, and built up the economy. Woodrow Wilson was an outspoken guy, worked out at Basic Magnesium, and would try to get political action going through the union.

“They did not yet have enough muster to do a picket, and maybe the community wasn’t ready, but this movement could not have started without the efforts of those people.”

Hoggard and Wilson drew McMillan into the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and one night, out of the blue, somebody nominated him to be its next president. “I didn’t seek the office but once I had it I decided there were things I should do.”

Members noticed that Highland Dairy and Anderson Dairy both delivered milk to the black community of West Las Vegas, yet wouldn’t hire blacks as delivery men. First McMillan wrote the companies asking that they hire blacks. When there was no response, the NAACP decided to target the businesses, one at a time. They picketed Highland Dairy, without results. So blacks quit buying milk from Highland Dairy, and it went out of business. Anderson Dairy began hiring blacks.

About 1957 Hoggard, McMillan and a third man whose name McMillan couldn’t remember started a newspaper called “The Missile.” It was published from the NAACP office, and members donated money to support it. Until that time, explained McMillan, “It was difficult for us to get coverage. If we decided to boycott the Sands, for instance, we couldn’t get that in the paper and particularly not in the Review-Journal. Hank Greenspun would print some of our news in the Sun, but only what he agreed with. Not everything.”

After three years the founders decided they couldn’t continue pouring time and money into The Missile, so they sold it to West. West changed its name to The Voice, somehow turned a profit, and later sold it to a retired Air Force colonel, the late Ed Brown. Some 40 years later, the newspaper survives as the Las Vegas Sentinel Voice.

In 1960, four black college students sat down at the whites-only Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C., and refused to leave unless served. This first “sit-in” inspired similar ones. The NAACP sent letters to all its branches asking them to press forward while the mood of the country seemed receptive.

The most glaring offenders in Las Vegas were casinos and restaurants where black would-be patrons were denied admission. “So I sent a letter to the mayor … and gave him 30 days.” If the mayor failed to respond with a plan to eliminate discrimination, blacks would march on the casino districts.

Mayor Oran Gragson and City Commissioner Reed Whipple made a counteroffer. If the demonstration were called off, there would be more city jobs for blacks, and Whipple, an officer of First National Bank, would see that blacks started getting loans to build houses and start businesses. But they didn’t promise to force resorts to admit blacks, claiming they lacked jurisdiction.

To his dying day, McMillan wondered if he should have rejected the deal as he did. West Las Vegas might not have remained so undeveloped and jobless as it did. “But … I felt that by eliminating the prejudice, the development would come anyway.”

McMillan was bluffing. He had not actually organized a protest and didn’t know whether he could. He had only 10 days to do it. The NAACP held meetings in West Las Vegas churches, trying to get citizens to commit to marching, perhaps facing fire hoses and clubbing and jail.

Meanwhile, McMillan was getting death threats from the Ku Klux Klan.

Sgt. Wilbur Jackson and the rest of Las Vegas’ handful of black police officers invented endless reasons their duties required them to drive by McMillan’s house several times a night. Entertainer William “Bob” Bailey organized volunteers to defend McMillan and his family.

Then McMillan got a phone call from Oscar Crozier, who owned a small gambling club in West Las Vegas. Crozier had been chosen to deliver a message from some of the hidden, mob-connected owners of Strip hotels: “Cut it out or we’ll drop you in Lake Mead.”

McMillan sent a message back through Crozier, saying, as he recalled it, “All I’m trying to do is make this a cosmopolitan city and that will make more money for them. You tell them that and let me know what they say.”

“I was almost ready to throw in the towel,” McMillan admitted in his autobiography. “If he had come back to me and said, ‘Man, they said no. You better cut this crap out,’ I would have peeked at my hole card.”

Instead, Crozier came back and said, “Mac, its OK. They’re going to make their people let blacks stay in the hotels. … Black people can go into restaurants and stay at hotels and gamble and eat and everything else.”

McMillan said in January, “I think the mobsters decided it was better to negotiate than to have cars burning on the Strip. We would have had to do something like that, you see. If not, they would just have sat on the sidewalk and laughed at us.”

The decision was announced at the Moulin Rouge and has become known as “The Moulin Rouge Agreement.”

McMillan resigned his position as head of the NAACP in 1961. He would serve two more two-year terms, but his reputation will forever stand on the 1960 confrontation when the mob blinked before he did.

He ran for U.S. Senate against Howard Cannon and Harry Claiborne, ran for County Commission against Bob Baskin and Harley Harmon, and lost each time. He did defeat an incumbent school board member, John Rhodes, and served one term before he was himself defeated in 1996 by a professional educator, Shirley Barber.

McMillan died of cancer on March 20, 1999. Only two months before that, he was still outspoken about his disappointment in public education, and advising that the public not take it lying down.

“I don’t think teachers are doing a good job,” he said. “It seemed impossible that we are taking kids all the way through sixth grade and they are not yet able to read, write or spell. Yet they are promoting a lot of kids instead of holding them back.” Schools remain poor because parents accept it, said McMillan.

“We need people to raise hell,” he said. “And if they can’t get the school district to function through their school board representatives, they need to picket, march and do whatever they can until it changes.”