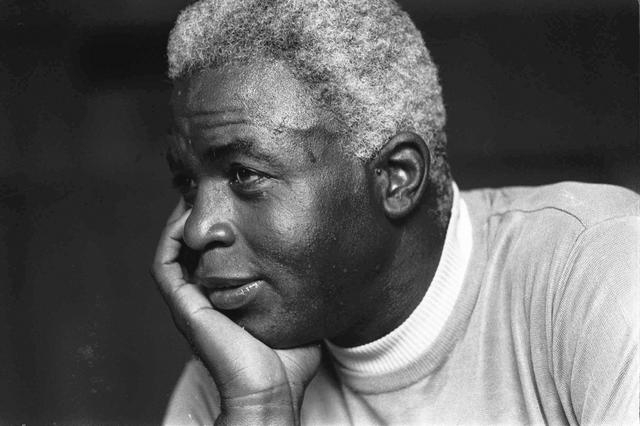

Jackie Robinson deserves national day of honor

“The right of every American to first-class citizenship is the most important issue of our time.” — Jackie Robinson

Like a slow grounder that slips between an infielder’s legs, it was an easy opportunity. And somehow we missed it, again.

April 15 came and went this year without a call going out across the land for the creation of a new national holiday. Not a holiday from taxes, as tempting as that thought is, but a day of recognition representative of something far more noble and inspirational — something that illustrates a historical landmark and an essential element of our nation’s character.

As baseball fans know, April 15, 1947, is the date Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers and became the first black ballplayer to reach the big leagues in the modern era. Professional baseball since 2004 has honored Robinson with a special day, and players show their respect by wearing his No. 42 on their jerseys.

It is a wonderful bouquet. Robinson’s breakthrough was a turning point for baseball, but it was also an important moment in our nation’s history. It’s one that I believe should be officially honored outside the sport.

With the passage of time, and thanks most recently to the documentary work of the great Ken Burns, Robinson is being better remembered for his outspoken place in the struggle for equality and civil rights. To narrow his contribution to that feat on the baseball diamond, as courageous as it was, misses the greater meaning of Robinson’s life and the important role he played in a still-segregated American society.

In addition to his historic tenure with the Dodgers, he became a successful businessman and penned a popular newspaper column with the New York Post. Like many blacks of his generation, he was a “Party of Lincoln” Republican, and as a national celebrity wasn’t shy about firing off letters and telegrams to the occupant of the White House. When President Dwight Eisenhower wavered on civil rights, Robinson wasn’t shy about letting him have it.

In a May 13, 1958, letter available on archives.gov, Robinson wrote in part, “I respectfully remind you sir, that we have been the most patient of all people. When you said we must have self-respect, I wondered how we could have self-respect and remain patient considering the treatment accorded us through the years.

“17 million Negroes cannot do as you suggest and wait for the hearts of men to change. We want to enjoy now the rights we feel we are entitled to as Americans. This we cannot do unless we pursue aggressively goals which all other Americans achieved over 150 years ago.”

Mention Robinson today to blacks of a certain generation, and there’s no hesitation about his place in the civil rights pantheon.

Back in 1947, it took a while for word of Robinson’s feat in far-off Brooklyn to reach Mound, Louisiana, where a 12-year-old Joe Neal worked in sharecropped fields and attended a segregated schoolhouse.

But once the news was broadcast on an old battery-powered radio, “Jackie Robinson was immediately looked upon as a hero,” Neal recalled recently. At 80, Neal made political history in 1972 by being elected Nevada’s first black state senator.

“When I was growing up, everyone in the neighborhood was playing some type of baseball. And if you didn’t have a baseball, you made your own,” Neal said. “Being in Mound, we were a long way from big cities that had Major League Baseball teams. We were somewhat familiar with some of the black teams that were playing in those days. And of course there were the black traveling baseball teams. We were not familiar with the stuff Jackie Robinson had to go through until years later. But when we learned of what he’d done, all the people became great fans of Jackie Robinson, and later Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe.”

Robinson made himself heard loud and clear. For those who grew tired of hearing a black man with a national audience speak out on race and civil rights, he replied, “Civil rights is not by any means the only issue that concerns me — nor, I think any other Negro. As Americans, we have as much at stake in this country as anyone else. But since effective participation in a democracy is based upon enjoyment of basic freedoms that everyone else takes for granted, we need make no apologies for being especially interested in catching up on civil rights.”

He was an all-star in many fields.

The man whose courage helped make America a better place famously said, “I won’t ‘have it made’ until the most underprivileged Negro in Mississippi can live in equal dignity with anyone else in America.”

Robinson’s life is a reminder there are things much more important than home runs and earned-run averages.

Although as disappointed baseball fans know there’s always next season, there’s no time like the present to make sure No. 42 receives the official national recognition his memory deserves.

John L. Smith’s column appears Sunday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday and Saturday. Contact him at 702-383-0295 or jsmith@reviewjournal.com. On twitter: @jlnevadasmith