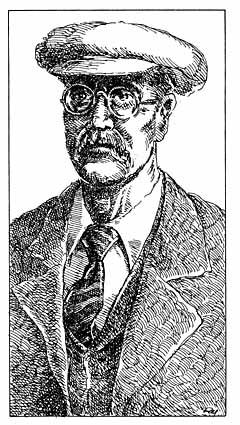

J.T. McWilliams

His face was as red as his hair when J.T. McWilliams reached the crest of the Spring Mountain Range. He paused, wiped the sweat from his face and thick spectacles, and peered down heavily forested Lee Canyon.

On that day in 1894, he saw more trees than he had seen anywhere since he came West, and he saw money to make from timber sales. But as he explored the canyon, he saw a higher use for the land, and he would spend the next four decades working to open the mountain canyon to public recreational use, and to preserve its natural splendor.

McWilliams had been in the region for about a year and was working in Goodsprings, where there was plenty to do for a surveyor and civil engineer. At some time during his first year there, he met Noah Clark, who operated a sawmill in Clark Canyon, on the Pahrump side of the Spring Mountains. The sawyer told him of the vast, unclaimed forest land on the other side of the hill, and McWilliams set out on foot to inspect it for himself. He immediately set about surveying the land, and laid claim to about 1,300 acres of it.

“This proved a long and expensive process because others who had money and great influence were also smitten with the ambition to secure this timber for its value as lumber,” said The Las Vegas Age of Aug. 20, 1937. It was not surprising, therefore, that in 1906, through the power of some Washington politicians, the McWilliams permits were ordered canceled.

He never quite identified the “Washington politicians,” but doubtless suspected William A. Clark, who was not only a U.S. senator (from Montana) but also proprietor of the San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad, which had built Las Vegas and controlled most local development. Clark had made fortunes not only in copper but also by exploiting timber, and furthermore, seemed to consider McWilliams an enemy.

McWilliams responded to the cancellation of his claims by writing a long letter to President Theodore Roosevelt, no lover of the big railroads, and telegraphing it to Washington. Within four days, his claims were validated.

It was one of many battles the feisty McWilliams would wage with the railroad between 1902 and his death in 1941, and one of the few he would win.

John Thomas McWilliams was born at Owen Sound, Ontario, Canada on Dec. 10, 1863, one of four brothers. His father, John McWilliams, was a building contractor who had immigrated from Ulster in what is now Northern Ireland. Young McWilliams learned surveying by working as an apprentice, but aspired to a career in engineering.

On a visit to the United States in 1879, J.T. McWilliams decided he liked America and moved to Detroit, where he worked in a wholesale grocery. In 1883, he moved to Chicago. By day he was a grocer; by night, he attended classes in civil engineering at the University of Chicago. By the next year, he was employed by the Northern Pacific Railroad in its engineering corps.

At some point, he must have made influential friends, because in 1893, the governor of South Dakota appointed him a delegate to the National Irrigation Congress in Los Angeles. When the conference concluded, he decided to tour the region, where he found a wealth of work for a man with his skills — particularly for someone experienced in surveying railroad grades.

In 1897, he was on a job in Needles, Calif., when he met his future wife, Iona. She had been born in Grand Rapids, Minn., in 1876, educated as a schoolteacher in Philadelphia, and had moved to Needles on the advice of her doctor when she developed a lung ailment. She had fully recovered by the time she married McWilliams at Fort Mohave in 1897.

His next job took the newlyweds to Flagstaff, Ariz., where McWilliams designed the town’s first water system, and the couple welcomed their second child, Nellie, in 1898. (The first, a boy, had died at birth.) In 1899, they moved to the Grand Canyon, where McWilliams surveyed the Bright Angel Trail into the canyon. The family lived in a small house located about halfway between the canyon rim and the river.

In 1901, the family moved to Goodsprings, determined to settle in that booming little town. There was plenty of work in the region for the breadwinner, and a particularly interesting job came his way in 1902, when he was summoned by William McDermott, who represented the newly formed San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad, to come to Helen J. Stewart’s Las Vegas Ranch. It seemed that the railroad wanted him to survey the 1,840-acre ranch, which it was considering as a new townsite and railroad division point.

McWilliams, who probably knew the region as well as anyone of the time, and was aware of the valley’s huge artesian water belt, peered through his surveyor’s transit and saw opportunity. It would be the last time for a long time that he would deal with the railroad on friendly terms.

Around 1904, he purchased 80 acres of land from Stewart on the west side of the railroad right of way, and carefully laid out an orderly townsite with broad avenues. McWilliams saw it as the ideal site, close to Las Vegas Creek, and accessible to the road to Rhyolite, Goldfield and Tonopah.

To an extent, he was right. The lots sold well through the winter of 1904-1905, and the town reached a peak of 2,000-3,000, many of those teamsters who plied the trails between Las Vegas and the northern mines. But the railroad was not about to allow an upstart surveyor to reap any benefits that it could retain for itself. The company established its own subdivision, the Las Vegas Land and Water Co., which laid out the Las Vegas Townsite, the core of present-day downtown Las Vegas. Lots were sold during a two-day auction in May of 1905. The high demand can be explained in a word: water. The railroad owned nearly all the water from Big Springs, the source of Las Vegas Creek, and lots in the townsite came with the promise of water. McWilliamstown was served by a hodgepodge of small wells, some of which served several lots. Many of the people who had originally bought lots and erected permanent structures put them on skids and dragged them across the tracks to the new townsite.

Still, optimism flourished. McWilliams built his house there, and persuaded well-known impresario Chuancy Pulsifer to build a vaudeville theater, The Trocadero. Work began on the 800-seat theater in May 1905, and ceased a few weeks after the Las Vegas auction of lots. The unfinished building languished, and finally was felled by one of a series of fires that destroyed most of the town’s few remaining wooden buildings.

Until the 1930s, the town would consist mostly of tents and shacks. By 1906, the year McWilliams was appointed State Water Rights Surveyor for the region, the snobs across the tracks were referring to it as “Ragtown.” McWilliams insisted that it be called “the Original Las Vegas Townsite.” Both he and Sen. Clark’s Las Vegas Land and Water Co. had, since early 1905, been advertising heavily in the Los Angeles newspapers. Clark’s ad’s touted the easy availability of water; McWilliams, his low prices and easy terms.

There was no love lost between Walter Bracken, the railroad’s lackey in Las Vegas, and the feisty surveyor. But it was the fabled icehouse incident that upgraded their mutual disdain to outright hatred. C.P. “Pop” Squires, editor of The Las Vegas Age, recalled in a 1933 article that the construction of an icehouse was a priority in the early years of the town, and that Sen. Clark himself rode past a plot of land on the north end of town and indicated that he wanted the ice plant located there. His will was done, and workers soon had completed the foundations for a fine, large structure.

Meanwhile, McWilliams, who had been in Los Angeles when the work commenced, returned. He took one look at the site, must have laughed, and fetched his surveying instruments. His suspicions were confirmed; the ice house was on his property. (It was a small, triangular section located at what is now the corner of Main Street and Bonanza Road.)

It is unclear whether McWilliams deliberately waited until the work was well along before notifying the railroad of its mistake, or if he had actually been unaware of what was happening. In either case, McWilliams apprised Bracken of the error and offered to sell the lot for $1,000. Bracken, who was responsible to the company for such screw-ups, took the position that McWilliams was once again trying to take advantage of the poor railroad. There was no sale. The railroad simply ceased work, and moved the project elsewhere. McWilliams later sold the land for several thousand dollars.

McWilliams had discovered a new hobby; annoying Bracken. The surveyor seemed to enjoy the role of gadfly, and it was certainly a job that needed to be done in such a solid company town. On the other hand, it may have been in McWilliams’ nature. There is plenty of evidence that he possessed the Celtic cultural trait of enjoying a good row.

Sometime around 1914, McWilliams was beaten senseless by Joe May, who had taken exception to something McWilliams had said about him. McWilliams filed charges of assault and battery, and May demanded a jury trial. The defense “called several witnesses to prove that McWilliams’ reputation for peace and quietude is bad,” The Age reported. “Sheriff Woodard was called in rebuttal and testified that McWilliams has been on good behavior for the past six months.” May was fined $50.

Though he was not among the city’s original elite because of his estrangement from the railroad, McWilliams continually showed his interest in the town and the region. And, as the town grew, his reputation grew along with it. He maintained his civil engineering practice and he produced more than 3,000 maps of Clark County and all its subdivisions, a project that kept him busy the rest of his life. Not so busy, though, that he couldn’t pause to give Bracken a bellyache.

In their book “Water: A History of Las Vegas,” Florence Lee Jones and John Cahlan provided a detailed account of the next battle between Bracken and McWilliams. In May, 1912, McWilliams happened upon some workmen emptying the cesspool of the railroad shops directly into Las Vegas Creek. He wrote to Bracken, noting that a herd of dairy cattle, from which the city obtained all of its milk, was drinking from the creek below where the dumping was going on. He also pointed out that the creek was used by the ranch’s slaughterhouse, and said, “the only supply of meat Las Vegas has is butchered in the slaughter house, and must be washed with sewerage water.”

The railroad ceased dumping and laid a water line to the slaughterhouse.

By 1916, McWilliams and the residents of what had come to be called “Old Town,” were pressuring the railroad’s land-and-water subsidiary to provide water to the subdivision, and the Las Vegas City Commission passed a resolution that year asking it to do so.

However, the clamor continued until, in 1926, its residents petitioned the Nevada Public Service Commission for service. Long, complicated and occasionally rancorous negotiations continued until the fall of 1927, when it was finally agreed that Old Town – and no other subdivisions – would receive city water. McWilliams was hired to lay out the system. In the end, the cost to the railroad company to deliver water to Old Town was $87.40 per month, while income from water sales amounted to $271.81 per month.

McWilliams didn’t have water on the brain, though, and through all his water battles, he saved time for his pet project, the development of his land in Lee Canyon. As early as 1910, he and his wife had established a camp in the pines, and advertised it in The Las Vegas Age, advising customers to “bring your own grub and bedding.”

By the early 1930s, McWilliams owned or controlled more than 2,000 acres of the best land in Lee Canyon. He was deluged with offers from entrepreneurs who wanted to log the property, most of which were declined. What McWilliams had in mind was a small community of rustic cabins, with campgrounds, hiking trails and access roads throughout the area.

He got acquainted with Claude Mackey, local representative for the Works Progress Administration, one of the Roosevelt administration’s New Deal programs. McWilliams offered the WPA 10 acres of his best forest land if the government would build a public playground for Southern Nevada children. Naturally, with the feds involved, the scope of the project increased dramatically. Mackey asked for an additional 40 acres, then another 10 acres. Then he asked for still another 50 acres and, finally another 10 acres on top of that to build a ski course. During 1937, a unit of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was installed, and the boys worked wonders on the area. In addition to building the main road — under the direction of McWilliams — they built a full-blown mountain resort with cabins, a kitchen and dining hall and hot showers. C.P. Squires, on a visit in 1937, was impressed.

“McWilliams Park … is the splendid result of determination and tenacity of purpose not often experienced in these days of dollar-grabbing.”

A transalpine road to Death Valley was never completed, though it might have been if McWilliams had lived through the war. In the fall of 1941, he suffered a heart attack and died a few days later. His wife continued to live in the house on Wilson Street that her husband had built in 1904 until she was put into a nursing home in 1968.

The outsider who bucked the railroad big boys had gained considerable status since his arrival, and his death was front page news. His “crank” individualism was lauded, and he was recalled as a great pioneer. In 1927, he made a statement, in passing, that sounded suspiciously like the utterance of a visionary.

“I gladly gave my time,” he said, “for the future of what will be a magic city.”