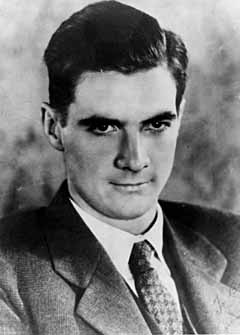

Howard Hughes

The year 1966 brought Las Vegas bad news, and good news.

The bad news was that mobsters were skimming Las Vegas casinos. The good news came when billionaire Howard Hughes arrived quietly and began buying casinos and real estate.

The eccentric billionaire, it was speculated, was on a mission. He would de-mob Las Vegas, make the city safe for legitimate business.

Mob activity declined during Hughes’ four years in Las Vegas, partly because he bought out many of the old-timers, but more because the federal government was turning up the heat.

Just by showing up, Hughes changed Las Vegas forever. If one of the richest men in the world, one of the nation’s largest defense contractors and a genuine national hero, was willing to invest in Las Vegas, it must not be such a sordid, evil place after all.

“He cleaned up the image of Las Vegas,” said Robert A. Maheu, who spent 13 years working for Hughes. “I have had the heads of large corporate entities tell me they would never have thought of coming here before Hughes came.”

The Hughes fortune is based on a drill bit patented in 1909 by Howard Hughes Sr. and Walter Sharp. The first bit that could easily penetrate solid rock, it revolutionized oil drilling, and made Hughes and Sharp rich. In 1922, Hughes’ mother died. Two years later, his father died.

His uncle, Rupert Hughes, and the rest of his extensive family expected the orphaned 18-year-old to finish Rice University. Instead, he dropped out and announced his plans to take over his father’s tool company. Not content to be the majority stockholder in a family business, he tried to buy his relatives’ stock. By the time it was over, Hughes owned all stock in the company and had alienated his entire family.

In Los Angeles, Hughes met Noah Dietrich, a former race-car driver turned accountant, and hired him in 1925. Most historians agree that it was Dietrich who transformed Hughes from a wealthy man to a billionaire.

“There is no doubt about it,” affirms Maheu. “He was delivering Howard profits of $50 (million) to $55 million a year. Big bucks in those days.”

In June, 1925, Hughes married Houston socialite Ella Rice and they moved to Hollywood. He kept her isolated at home for weeks, and she returned to Houston and divorced him in 1929. His second wife, actress Jean Peters, married Hughes in Tonopah in 1957, divorced him in 1970. Except for a brief period in 1961, they lived apart.

Meanwhile, Hughes cultivated his image as the playboy filmmaker who discovered Jean Harlow and Jane Russell; the daredevil aviator who broke speed records in airplanes he designed. After his round-the-world flight of 1938, he became a national hero on par with Charles Lindburgh.

In 1946, while test-piloting the XF-11 photo reconnaissance plane, Hughes crashed the plane in Beverly Hills, Calif. He wasn’t expected to live. The crash broke nearly every bone in his body, and doctors administered morphine liberally to ease his intense pain, beginning a lifelong addiction to opiates.

Even so, he remained a regular visitor to Las Vegas casinos during the 1940s and ’50s, seen occasionally at the tables, more often escorting a gorgeous young woman into a restaurant or showroom. In 1950, he announced Hughes Aircraft would move from Culver City, Calif., to a 25,000-acre tract west of Las Vegas. He had felt oppressed since California levied an income tax in 1935. However, his key executives and technicians at Hughes Aircraft had flatly refused to be exiled to the desert, and the “Husite” property remained vacant.

By 1957, Hughes was seriously drug-addicted and in total isolation. Maheu, a former FBI special agent, was regularly taking assignments, thwarting blackmailers, spying on Hughes’ girlfriends, and increasingly, acting as personal emissary.

“He decided that he wanted me to become his alter ego so he would never have to make a public appearance.”

They never met face-to-face. Communications were always by phone or memo. Maheu believes Hughes went into seclusion because he was going deaf, and was too proud to wear a hearing aid.

By 1961, Maheu had moved from Washington to Los Angeles to become Hughes’ surrogate. The pickings were lush. In addition to a $520,000 yearly salary, Maheu had an unlimited expense account, access to Hughes’ jet and the social status of a Saxon lord. But his king was unhappy, and still wanted to move to Nevada.

“I’m sick and tired of being a small fish in the big pond of Southern California,” Hughes complained. “I’ll be a big fish in a small pond. I want people to pay attention when I talk.”

In 1966, the Desert Inn rented Hughes its entire top floor of high-roller suites, and the floor below it, for 10 days only. Check-out time came and went, and Hughes didn’t move. Moe Dalitz and Ruby Kolod, co-owners of the Desert Inn, were furious. New Year’s, one of Las Vegas’ busiest holidays, was looming, and the suites had been promised to high rollers. The squeeze was on Maheu.

“Get the hell out of here or we’ll throw your butt out,” growled Kolod.

“It’s your problem,” Hughes told Maheu. “You work it out.”

Maheu called in a favor from Teamsters Union President Jimmy Hoffa, who phoned the DI boys and asked them to leave “my friends” alone. The reprieve lasted into the new year of 1967, when Maheu told the boss he had played out his options with the DI guys.

“If you want a place to sleep, you’d damned well better buy the hotel,” Maheu told Hughes.

To most investors, negotiating a purchase is the means to an end. To Howard Hughes, it was recreation. After months of arduous log-rolling, Hughes and Dalitz agreed on a price of $13.25 million.

Seven months before his arrival in Las Vegas, Hughes sold his stock in TransWorld Airlines, and had received more than $546 million. The IRS taxed that money as “passive” income, at a higher rate than “active” or “working” income. After the DI purchase, Hughes discovered the gross receipts of a casino are considered active income. Ecstatic, he called Maheu.

“How many more of these toys are available?” he demanded of Maheu. “Let’s buy ’em all.”

“(He) would use every gimmick in the book; he’d pay someone half a million dollars if they could help him avoid paying $10 worth of taxes,” said Maheu. “I knew that we’d never make it in the gaming business,” said Maheu. “For the simple reason that he had a standing rule that we could not make a capital investment of $10,000 or more without his approval — and he never gave his approval.”

Johnny Rosselli, known as the mob’s “ambassador” to Las Vegas and Hollywood, approached Maheu and told him who was going to be the new casino manager. Maheu told him to go to hell.

Not only was he not in bed with the mob, claimed Maheu, he was actually working quietly to ease them out of town.

“If you look at what we bought, you’ll find that we must have known something,” said Maheu. “It was not an accident.”

That “something,” explained Maheu, was a study commissioned by former Attorney General Robert Kennedy, a blueprint for exorcising the mob from Las Vegas.

“In it, the places that had to be cleaned up were identified,” said Maheu. “And it said that the best way to clean them up was by purchase. So you put all the elements together, and who is better equipped with the money than Hughes?”

In order to be licensed as operator of the Desert Inn, Hughes would have to undergo an extensive background check. He also would have to appear before the state Gaming Commission, which he had no intention of doing. Well-connected Las Vegas attorney Thomas Bell was hired to handle the licensing, and would stay on as Hughes’ lobbyist in Carson City. The new governor, Paul Laxalt, persuaded the commission to allow Maheu to appear as Hughes’ surrogate.

“Laxalt saw Hughes as a better option than the mob,” said Maheu. “He was an excellent businessman and he was totally legitimate — the kind of sugar daddy Las Vegas needed.”

The next purchase was the Sands, then a Strip showplace. Dalitz was consulted, and allowed that it “would be a good acquisition.” Hughes paid $14.6 million for the Sands, which included 183 acres of prime real estate that would become the Howard Hughes Center. That was followed by two smaller places, the Castaways and the Silver Slipper, then the Frontier. All three had one thing in common, they came with enormous parcels of empty land. He made a deal to buy the Stardust for $30.5 million, but was prevented from closing by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, which was worried about Hughes holding a monopoly on Las Vegas lodging.

“If we had been allowed to buy the Stardust, you wouldn’t have had … all the terrible publicity from that movie ‘Casino,'” said Maheu.

Hughes also purchased the local CBS affiliate, KLAS-TV, from Las Vegas Sun publisher Hank Greenspun because, as a night owl, he wanted to control which old movies it ran in the wee hours.

“Once he was in both (the gaming and hotel business) he didn’t want anyone bigger than he,” said Maheu. “That’s why he tried to stop Kirk (Kerkorian) from building the big place. But he was not willing to do it at the expense of himself continuing to build, or expanding the ground that he had. It doesn’t make sense, but it happens to be the truth. He wanted to be the biggest; he didn’t want Del Webb to ever be as big. When he bought a piece of land, he wanted all the land around it. He wanted to control. He would have been very happy to be the biggest if no one got bigger than that.”

Kerkorian’s International Hotel (now the Las Vegas Hilton) began to rise in early 1968. So did Hughes’ anxiety. He announced plans for a $100 million “Super Sands,” hoping Kerkorian would flee into the desert at the news. He didn’t.

Hughes saw the solution to “the Kerkorian problem” in the Landmark. The tower, a fat concrete cylinder topped with an oversized saucer, rose in the early 1960s, but sat dark most of the decade. Its problem was its design. It had too few rooms, too little casino space. But at 31 stories, it was slightly taller than the International. For that reason, Hughes wanted it.

“A lot of people have given me credit for paying 100 cents on the dollar ($17.3 million) for it.” said Maheu. “It wasn’t my idea, it was his. He was on a public relations kick at the time.” Hughes said he would personally direct planning for the grand opening.

“I knew from that point on that I was in trouble,” said Maheu. “He was completely incapable of making decisions.”

Kerkorian’s camp had announced that the International would open July 2, 1969. Maheu suggested the Landmark open July 1, but Hughes wanted the opening date left flexible. The International’s opening act would be Barbra Streisand. Hughes’ ideas bordered on fantasy. He suggested a Bob Hope-Bing Crosby reunion, or getting the Rat Pack together for a “Summit at the Landmark.”

Hughes obsessed endlessly over names on the guest list. Maheu would send him a list, and Hughes would return it with all but one or two names crossed out, and a couple added. The guest list made dozens of trips from Hughes’ suite to Maheu’s office.

“I had to go ahead and make the arrangements,” said Maheu, “otherwise we would have looked stupid.”

Although one of the country’s most generous campaign donors, Hughes was apolitical. He backed whichever candidate he felt would do him the most good, but always hedged bets by spreading plenty of cash among incumbents and challengers alike. Nixon had cost millions.

During Hughes’ time in Las Vegas, donations were disbursed by attorney Bell, who had a knack for sizing up new political candidates, assessing their chances , and proffering an appropriately sized bankroll.

“All the money came from the cage at the Silver Slipper,” notes Maheu.

Howard Hughes didn’t expect much for his largesse. He simply wanted to control every aspect of Nevada public policy. He gave Bell a legislative shopping list. He wanted to prevent dog racing from becoming legal; repeal the sales tax as well as gasoline and cigarette taxes; stop the integration of Clark County schools; prevent communist bloc entertainers from appearing on Nevada stages; pass a special law exempting him, Howard Hughes, from being forced to appear before any court or board, and a bill to outlaw rock festivals in Clark County. He also wanted to prohibit governmental agencies from realigning any streets without first consulting him. The list went on, but Hughes was especially wary of civil rights legislation.

Howard Hughes was Afrophobic. He had been a child in 1917 when one of the nation’s worst race riots broke out in Houston, his home town, leaving 17 dead.

Maheu, a tennis devotee, had managed to bring the Davis Cup championship to the Desert Inn. Promising to fill the hotel with well-heeled guests, Maheu felt pleased with himself. But on the night before the tournament, Hughes discovered that one contender was tennis superstar Arthur Ashe, a black man. Hughes wanted the match canceled, fearing the Desert Inn would be invaded by “hordes of Negroes.” Maheu quelled his fears, and the match went on.

But no one could quell his fear of disease and germs, perhaps his mother’s most profound phobia. If Howard sniffled or coughed, he was rushed to a doctor, lavished with attention and sympathy. Allene Gano Hughes saw every playmate as a disease carrier, and discouraged her only son from socializing.

Paradoxically, Hughes wallowed in his own filth in his DI penthouse, which never, during his entire tenancy, was cleaned. He stored his bodily waste in jars in the closet, never sterilized his hypodermic needles and rarely bathed, except when he “purified” himself with rubbing alcohol.

The Southern Nevada Water Project was the culmination of some 30 years of work by state leaders, and literally made it possible for Las Vegas to grow to its current dimensions by bringing water over the mountains from Lake Mead. But Hughes wanted it stopped at once. His objection was that while Las Vegas drew water from the lake, it also discharged treated waste water back into it. Hughes drank only bottled water, but was concerned for his customers.

“Nevada must not offer its tourists water from a polluted, actually stinking lake,” Hughes wrote. “This water is, in truth, nothing more or less than sewage, with the turds removed by a strainer so it can be pumped through a pipe.”

Gov. Laxalt listened politely on the telephone to a Hughes harangue, and promptly dismissed the whole nutty notion.

During all his years as a recluse, there were only a handful of people who saw him personally each day. This was the so-called “Mormon Mafia,” which took orders from Bill Gay, chief of Hughes’ Los Angeles office. Its mission consisted of feeding Hughes occasionally and drugging him regularly.

On Nov. 5, 1970, Hughes was carried from the Desert Inn and put on a jet for the Bahamas. It was, according to Maheu, a coup.

“The reason I know, is that that they tried to get me to join on two occasions,” said Maheu.

In April 1976, Hughes died at age 70 aboard a plane en route to Houston, ostensibly of kidney failure. However, his dehydration, malnutrition and the shards of broken hypodermic needles buried in his thin arms suggested other factors.

“If sheer neglect qualifies as a weapon,” said Maheu, “they killed him.”

Because no Hughes’ will was ruled legitimate, his empire was divided among his many cousins. The company, now renamed Summa Corp., finally began to show a profit. In 1996, the old Husite property was renamed for Hughes’ grandmother, Jean Amelia Summerlin.