Frank Sinatra

He made the city swing.

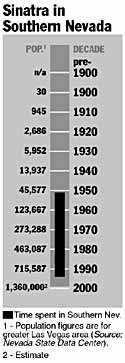

And that is neither to undersell nor overstate Frank Sinatra’s contribution to Las Vegas. Sinatra was a pop music legend, not a civic leader or entrepreneur. But Sinatra was a one-man chamber of commerce who gave Las Vegas something equally important: an image. And he did so in the mid-1950s, before demographics and visitor volume were buzzwords.

It was a simpler day in a smaller town, and Sinatra’s magic was more easily described: gambling, womanizing, drinking till dawn — and all of it with style.

“He brought unmatched excitement to the Strip and defined the word `swinger’ for all times,” said actor Gregory Peck at the Las Vegas golf tournament that bears Sinatra’s name.

“With his little gang of merry men he established forever a sense of free-floating fun and frolic that captured the imagination of the world,” Peck told celebrities two weeks after Sinatra’s death in May 1998.

Sinatra was a Las Vegas fixture for 43 years, from his first gig in September 1951 until May 1994. He first worked the glorified motel that was the Desert Inn and last performed at the 5,000-room MGM Grand.

Even before his death, his life was legend. “That Sinatra aura brought international royalty and made us a global destination,” says Lt. Gov. Lorraine Hunt, a former entertainer and Clark County commissioner.

Aspects of the saga surely bend the corners of reality as all legends do. However embellished, the Rat Pack image of all-night ring-a-ding-dinging still holds a grasp on the “Cocktail Nation” of young swing-dance enthusiasts in the waning days of the century.

But trying to extract Sinatra’s legend from real Las Vegas history is tough. To play a game of “What if there had been no Sinatra?” is nearly impossible, because the rise of the singer and the Strip were inseparable.

“Prior to Sinatra, we were more of a Western-feeling town,” asserted Hunt. “He brought a sophistication to the Strip.”

Hunt was a teen-aged friend of Carol Entratter, daughter of Sands impresario Jack Entratter. His legacy also is inseparable from Sinatra’s.

When publicity agent Monte Prosser bought New York’s Copacabana club in 1946, he named Jack Entratter as its general manager. A year later, Entratter owned stock in the club and by 1949 had a controlling interest.

But in 1952, the 38-year-old Entratter cashed out to become general manager of a new carpet joint called the Sands.

Entratter relied on the loyalty of Lena Horne, Danny Thomas and other Copacabana stars to book the hotel’s Copa Room.

“That was an era when the hotel owners were all walking around in cowboy hats, and all these guys came in with the mohair tuxes with the black satin shoes. That look was so cool,” Hunt recalls. “I remember being a teen-ager, I was so attracted to those shiny shoes.”

The Sands came along at a perfect time for Sinatra. His first visit to Las Vegas had been less than auspicious, coming in the midst of a nationwide scandal over leaving his wife Nancy for actress Ava Gardner.

Though still only 35, Sinatra was virtually a has-been. The young sensation from Hoboken, N.J., had risen to the top since his first jobs singing for the Harry James and Tommy Dorsey bands in 1939. His distinctive voice, boyish charm and lanky, nonthreatening build made him a favorite of the female “bobby-soxers” who crowded New York’s Paramount theater during World War II.

Sinatra’s career seemed to stabilize after the war and he looked like a permanent presence. But by the end of the decade it had all gone sour. His records for Columbia weren’t selling, his movies weren’t popular and the bobby-soxers had moved on to postwar nesting.

Sinatra first played Wilbur Clark’s Desert Inn on Sept. 4, 1951, just a few days after a reported suicide attempt in Lake Tahoe that was quickly discounted by both the singer and local authorities. He called it a sleeping pill miscalculation; others called it Ava-baiting.

By the time Sinatra debuted at the Sands on Oct. 7, 1953, he had divorced, remarried and was almost divorced again.

The next March, he picked up a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for “From Here to Eternity.”

Sinatra’s renewed momentum had carried over to his recording career. Leaving Columbia for Capitol, he entered a second, more mature phase. Working with arranger Nelson Riddle, he emerged from the winter of 1953 with “Songs for Young Lovers,” one of the first conceptual long-play record albums.

Vegas suddenly had a new soundtrack, albeit in old standards such as “My Funny Valentine” and “I Get A Kick Out of You.” “Sinatra perpetuated this music of Gershwin and Porter,” singer Paul Anka notes.

“Pop music was at its infancy stage and just growing … It was just a bunch of us kids,” says Anka, who first played the Sahara in 1959 when he was only 18. “So consequently (the casinos) went to these older established acts” from the nightclub circuit.

Television also was coming of age. It was a revolution that helped Las Vegas, and not just because it was right in the pathway to the West Coast TV mecca. Stay-at-home viewing habits suddenly put the crunch on supper clubs in other cities — giving Las Vegas casinos a clean sweep at the acts.

But nightclub veterans such as Jimmy Durante and Joe E. Lewis were really holdovers from a pre-war era.

Suddenly, with the Rat Pack it all jelled. “Now you’ve got the greatest, cool, hippest entertainers around,” Anka says of the expanding circle of hepcats.

By the end of the decade it included Dean Martin — who split with partner Jerry Lewis and began working the nightclubs as a solo act in 1957 — and Sammy Davis Jr., the young breakout sensation of the Will Mastin Trio. Joey Bishop, who had been working steadily as an opening act, was welcomed into the fold as a warm-up and uncredited gag writer for much of the “improvised” mayhem onstage. There was even room onstage for the less heralded journeyman comedian, Buddy Lester.

The nascent Strip wasn’t full of theme architecture and daytime diversions as it is today.

“The stars were the draw. They weren’t the cherry on the cake like they are today. They were the cake,” Anka says.

And the stars came to see Sinatra. “He was actually the king of Las Vegas, because the minute he stepped in town, money was here,” says veteran Las Vegas lounge singer Sonny King, a longtime friend of Sinatra. “He drew all the big money people. Every celebrity in Hollywood would come to Las Vegas to see him, one night or another.”

And the Sands became his playground. Part of it was loyalty, part of it business. “Sinatra’s allegiance to Jack Entratter was because (at the Copacabana club) Jack stood by him through all his troubles,” says veteran lounge singer Freddie Bell.

Entratter also was, King notes, “the first guy to give them points in the hotel. If you messed up and didn’t show up, you would lose money.” Within weeks of his first engagement, Nevada gaming authorities approved Sinatra’s application to buy 2 percent of the Sands for $54,000. By 1961, Sinatra owned a reported 9 percent share of the hotel, valued at $380,000.

As the Rat Pack charmed Eisenhower-era America separately and together through every available forum — radio, television, movies and nightclubs — the Strip continued its expansion. By the end of the ’50s, the Tropicana, Dunes, Stardust and Riviera had joined the horizon, while older hotels expanded.

The shining pop culture moment for both Sinatra and the city came with the “Summit at the Sands,” held from Jan. 26 through Feb. 16, 1960, playing on a summit meeting in Paris between President Eisenhower, Russian leader Nikita Khrushchev and French President Charles De Gaulle.

For the Rat Pack, the legendary showroom nights — performing all together or in various combinations — anchored filming of “Ocean’s Eleven.” The caper comedy was produced by Sinatra’s own Dorchester Productions as a vehicle for the entire Rat Pack. The gang now included Peter Lawford, convenient in an election year when Sinatra was enamored of Lawford’s famous in-law, Sen. John F. Kennedy.

The routine became famous: Two freewheeling, seltzer- spraying shows each night in the Copa Room, followed by a 2 a.m. sojourn in a carefully guarded Sands lounge, where the boys would invariably end up onstage again. Then sleep — depending upon when the filming schedule required a couple of hours on the set from one or more of the stars. Around 5 p.m. everyone convened in the steam room.

“Nothing has ever, or will ever, compare to that evening,” Gov. Bob Miller recalls of the Rat Pack show he saw as a teen-ager. “That was clearly the best show in the history of this community.” The magic was fueled by the Camelot spirit of the election year, capped by a visit from JFK himself on Feb. 8.

But Kennedy’s November 1963 assassination began to close the door on the era. Vietnam, civil unrest and the Beatles would change the face of pop culture.

A month earlier, on Sept. 11, 1963, the Nevada Gaming Control Board had recommended that Sinatra’s gambling license be revoked for allowing Chicago crime boss Sam Giancana to visit the Cal-Neva Lodge at Lake Tahoe. Nevada had published a “List of Excluded Persons,” who were not allowed in casinos even as customers, and Giancana was infamously on that list.

Sinatra “never could understand” the stigma of friendship with Giancana, said Phyllis McGuire, who was Giancana’s girlfriend during the controversy. “He’d been friends with the boys for years, ever since he needed to get out of his contract with Tommy Dorsey.”

Sinatra surrendered his casino license at the Cal-Neva and agreed to sell his interest in the Cal-Neva casino and in the Sands.

The whole country seemed to fly off track in the ’60s, and the desire to run with the new youth culture may help explain why a 50-year-old Sinatra married a 21-year-old Mia Farrow at the Sands on July 19, 1966. The marriage would last two years.

The biggest change for Sinatra came when Howard Hughes bought the Sands in 1967. The new management failed to continue the liberal accounting policies used to justify Sinatra’s casino debt, and the singer flew off the handle one night in September after his credit was cut off.

“He got up on that table and started yelling and screaming right in the middle of the casino,” says Anka, who claims to have witnessed the debacle. Hotel Vice President Carl Cohen was summoned, and when Sinatra threw a chair his way, the burly casino boss punched him in the mouth. The blow knocked the caps off Sinatra’s two front teeth, according to newspaper reports at the time.

Sinatra jumped ship to Caesars Palace in November 1968.

But there was trouble again in 1970, when casino executive Sanford Waterman pulled a gun on Sinatra after another argument over casino credit. Sheriff Ralph Lamb threatened to throw the singer in jail. “I’m tired of the way he has been acting around here anyway.”

“The love affair slowly started to unravel,” Anka says of the crooner and Las Vegas. Sinatra said he had “suffered enough indignities … If the public officials who seek newspaper exposure by harassing me and other entertainers don’t get off my back, it is of little moment to me if I ever play Las Vegas again.”

That was a precursor to a show business “retirement” that lasted from 1971 until a ballyhooed return to Caesars Palace on Jan. 25, 1974. “He omitted `My Way’ (because the end is no longer near?) and did a graceful exit with “I’ve Got the World on a String,'” Review-Journal columnist Forrest Duke wrote of the comeback.

The mellowed singer performed at least six annual concerts that raised more than $5 million for the UNLV athletic program (The university presented him with an honorary doctorate in 1976.) And the singer’s name was instrumental in launching the “Nite of Stars” benefit for St. Jude’s Ranch for Children in 1966.

As Sinatra and Barbara — his wife from 1976 until his death — began to spend more of their time and charity at home in Palm Springs, Calif., Nevada gaming controllers gradually put to rest the rift that stemmed back to 1963.

In 1981, Sinatra listed President Reagan as a character reference and called Peck to testify on his behalf when applying for a license as an entertainment consultant at Caesars Palace.

The Gaming Commission voted 4-1 for approval.

The late 1970s and early ’80s were perhaps the nadir of Sinatra’s tuxedo-clad hipness, but the “has-been” never missed a year of packing showrooms in Las Vegas.

Buoyed by his last hit, 1980’s “Theme from `New York, New York,’ ” he continued to play Caesars, then young casino executive Steve Wynn’s revitalized Golden Nugget downtown from 1984 through 1987. From October 1987 through 1990, he joined old friends Martin and Davis in the rotation at Bally’s.

“As much as people have said Las Vegas was the burial ground (for entertainers), I totally disagree,” says Richard Sturm, the MGM Grand’s vice president of entertainment and marketing, who booked the Bally’s showroom in those days. “There was certainly a new audience watching Sinatra. You could see tons of younger people really standing up and getting into it.”

After two years at the Riviera, the Desert Inn briefly returned to old-style star policy, celebrating Sinatra’s 77th birthday with a gala in December 1992. By then, some longtime fans cringed as the singer struggled to remember words to standards he had been singing for years.

And yet, as Paul Anka said in 1993, “If I know this man, he must work. To tell him he can’t work — it ain’t gonna fly.”

Sinatra cast his long shadow on one more hotel, the new MGM Grand, during the grand opening New Year’s holiday of 1993-’94. But his dates were overshadowed by Barbra Streisand’s return to live performing. Yet, even in death, Las Vegas is Frank’s town more than it will ever be Barbra’s. The lights dimmed on the Strip — albeit briefly and haphazardly — the night after Sinatra’s fatal heart attack at his Palm Springs home on May 14, 1998. But The Chairman would never have wanted the action to slow down for long.

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full