Experts: Early investment in literacy has biggest payoff

The vast majority of Nevada students struggle to read, conceded several local education officials on Tuesday.

They didn’t debate the data. They focused on how to change it.

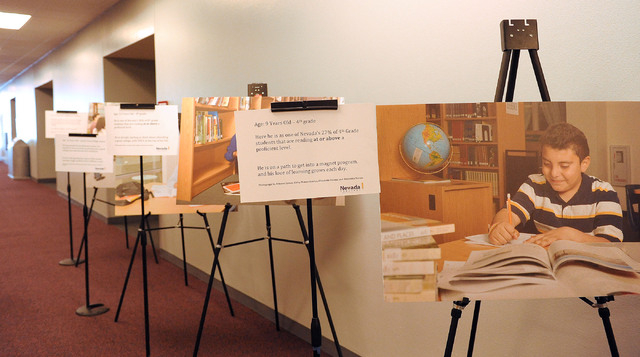

Federal assessments show only 30 percent of Nevada eighth-graders read at the level they should, slightly more than the 27 percent of fourth-graders who are proficient in reading. Trace Nevada’s high school dropouts back to fourth grade and nine out of 10 of them were behind in reading skills, according to the Nevada Department of Education.

“The statistics in Nevada are unacceptable,” said Nevada Deputy Superintendent of Student Achievement Steven Canavero to 175 people representing a who’s who of state lawmakers and public school leaders gathered to hear about the battle against illiteracy.

The consensus among experts at the Nevada Literacy Summit at University of Nevada, Las Vegas: Invest early and make certain students have grade-level reading skills by the end of third grade. If they aren’t proficient, don’t advance them. Give attention early to students who are struggling, which will cost more in the short term but less in the long run as they reach middle and high school, said Margarita Calderon, senior researcher at Maryland’s Johns Hopkins University School of Education.

Policymakers in other states have already drawn that line in the sand, calling it “Read by Three.” Researchers regard third grade as the critical turning point where students need to transition from learning to read to reading to learn. Students can’t do that if they’re still learning to read.

Nevada has a literacy plan first created in 2011 that needs to be revisited, Canavero said. But the Nevada Department of Education won’t be the entity to mandate “Read by Three.”

“Students can write LOL … but not string a sentence together,” said U.S. Rep. Dina Titus, D-Nev., referring to herself as a “friend and advocate for help at the federal level.”

But the “Read by Three” decision isn’t up to the feds either.

It’s up to state lawmakers. They considered a proposal for “Read by Three” in 2013 as Assembly Bill 161. The state Education Department estimated a need for $14.7 million in new funds over two years to make it happen, largely because schools would need to implement statewide assessments for kindergarten through second grade. State testing currently begins at third grade. The policy also has been part of Gov. Brian Sandoval’s platform, who took the lead from Florida Gov. Jeb Bush. But the policy has gotten nowhere.

The funding request killed the bill, said Mary Laura Bragg, Bush’s education adviser and national policy director of the Foundation for Excellence in Education.

Florida was in a similar situation as Nevada 14 years ago. Almost 30 percent of all third-graders were “functionally illiterate” at that time, meaning they weren’t just behind in their reading skills but were unable to read or write at the basic level, she said. Despite the high rate of illiterate students, only 3 percent were held back, she said.

Florida lawmakers initiated a “Read by Three” policy, “turning kindergarten through third grades upside down,” she said.

In 2002, Florida held back almost 15 percent of all third-graders under the new policy. But fewer students scored poorly on assessments each year after that, with 8 percent of third-graders held back in 2012. The percentage of illiterate third-graders also fell from 29 percent in 2001 to 18 percent in 2012, according to test results.

In the meantime, other states have adopted similar policies, including Mississippi, North Carolina, Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Arizona, Bragg said.

But how much did it cost Florida, asked Clark County School Board member Carolyn Edwards.

Florida, a state with 5 times as many students as Nevada, only received $11 million in new funding from the state its first year to help young students and train elementary school teachers for literacy instruction. About 90 percent of the funding came from existing sources, she said.

For example, Florida mandated that half of the $36 million budgeted by districts for teacher training must be spent on reading instruction. There was “some struggle” from districts, she said.

“You have to make tough choices and fund your priority,” Bragg said. “These are tough choices, but there isn’t another option in my mind.”

Contact reporter Trevon Milliard at tmilliard@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0279.