Elvis Presley

Among the tons of shlocky “memorabilia” marketed after Elvis Presley died in 1977, one of the most interesting was a pair of whiskey bottles, both statues of The King.

One depicted him as “The Hillbilly Cat,” a knock-kneed teen-ager wearing pink socks and caressing an old-style microphone. The other was a full-figured man decked out in several pounds of jewelry and a bejeweled white jumpsuit, his arm outstretched as if throwing a punch.

When the Postal Service decided to issue an Elvis commemorative stamp, there was considerable controversy over whether the stamp should depict the 1950s teen-idol, or the elder entertainer, whose garish garb and bombastic stage presence would forever identify him as “The Vegas Elvis.” Both stamps were ultimately issued.

For Elvis, the transition was abrupt, dramatic and calculated. He was the first big-name rock ‘n’ roller to regularly headline in a Las Vegas showroom. Just in time, too, says Review-Journal entertainment writer Mike Weatherford.

Weatherford explains that during the late ’60s and early ’70s, Las Vegas had a feeble grip on its claim of being “The Entertainment Capital of the World.” The big stars of the ’40s and ’50s were losing their lustre, retired or dead. And very few survivors — Frank Sinatra was the exception — had the drawing power to fill the entire town. In his new, flashier incarnation, Elvis brought the national spotlight once again on Las Vegas, and made it a safe place for rock ‘n’ rollers to recycle themselves.

Two events converged in 1969 to create The Vegas Elvis. The first was the end of his movie career. In the span of 12 years, he had made 33 of the worst films of all time. In addition to trite scripts and one-dimensional acting, his on-screen songs were penned by some of the least-talented (read “cheapest”) songwriters available. It is a testament to the loyalty of his fans that all were profitable. However, as a screen star, Elvis was never taken seriously. His theme song, someone joked, was “All Washed Up.” By the late ’60s, he was hinting to his manager, Col. Tom Parker, that he would like to go back on the road.

The second crucial event in the evolution of Vegas Elvis was the opening in July 1969 of Kirk Kerkorian’s 1,500-room International Hotel, the largest in the world at the time. It had three showrooms; the biggest, the Showroom Internationale, was a 2,000-seat monster. Kerkorian’s vision for his new property was that of a city in itself, the first megaresort, a place with myriad entertainment choices. The hotel’s general manager, Alex Shoofey, a veteran casino man whom Kerkorian had enticed from the Sahara, needed big-name entertainers. He offered to let Elvis open the hotel.

“Absolutely not,” declared Parker. “We will not open under any conditions. It’s much too risky. Let somebody else stick their neck out.”

Risky, indeed. Elvis had performed before a live audience only once in 11 years, his 1968 “Comeback Special” for NBC.

He was badly out of practice. But he looked every inch Elvis, encased in a skin-tight leather suit. His voice had matured, deeper and more powerful than before. He sang the obligatory hit songs, and closed with a new one, “If I Can Dream,” his first hit record in years.

The critical success of the show was due largely to its producers Steve Binder, Bones Howe and particularly, Billy Goldenberg, who backed Elvis’ vocals with a full-sized orchestra. In Las Vegas and elsewhere, he would never again perform without at least 30 pieces and a legion of backup singers.

He had watched Barbra Streisand, chosen to christen the Showroom Internationale, and shuddered. She was in fine voice, but she brought no sparkly sets, no high-stepping chorus line, no jokesters, jugglers or tap-dancing armadillos. Talent wasn’t enough.

Parker signed Elvis to a four-week contract with the International, at $100,000 per week. The singer knew he had to build a new act from scratch, and he loved the challenge. But he hated being in Las Vegas. Again.

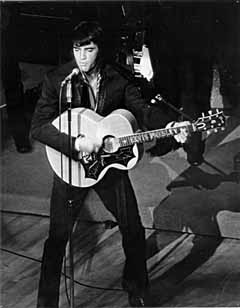

In the spring of 1956, just as Elvis’ career was taking off, Parker had booked him at the New Frontier for two weeks. He headlined a program that opened with the soothing strings of the Freddie Martin Orchestra, followed by the Borscht Belt humor of Shecky Greene. Then came Elvis, a 21-year old punk in a duck-ass hairdo, long sideburns and eye shadow. The collar of his pink shirt turned up, he slung his guitar forward and, with a sneer, began to play, no, to beat on it. He punctuated his vocals with what sounded like hiccups, and lurched around the stage in a spastic fervor.

Newsweek magazine likened Elvis’ presence in the show to a “jug of corn liquor at a champagne party,” and said the stunned audience sat motionless “as if he were a clinical experiment.”

Inside of two weeks, Elvis moved from the top to the bottom of the marquee, and vowed never again to play nightclubs.

Of course, what Elvis did or did not want was irrelevant. Parker was a showman in the mold of P.T. Barnum, a loutish, greedy, manipulative, cunning scoundrel who rarely concluded a deal without satisfying himself that his adversary had been flimflammed in some way.

It was the Colonel who insisted that Elvis join the Army.

After years of forbidding Elvis to marry, for fear he would lose his teeny-bopper fans, he suddenly decided it was time for Elvis to marry his fiance, Priscilla, with whom he had actually lived for several years. Again, he wanted to wring every molecule of positive publicity from the event. It would be in Las Vegas. The Colonel conned his old pal, Milton Prell, owner of the Aladdin, into hosting the wedding — that is, picking up the bill. The private ceremony was performed May 1, 1967, by Nevada Supreme Court Justice David Zenoff.

Elvis found the solution to his professional identity crisis in the lounge of the Flamingo in 1969. He’d been scouting showrooms and lounges, studying entertainers and audiences, looking for the raw material to craft “The Vegas Elvis.” In Tom Jones, a then-unknown Welsh singer, he found the prototype. Dressed in a skin-tight tuxedo, Jones would step to the edge of the stage, and lean far, far back, to give fans a good look at the outline of his genitalia. Elvis was impressed with the response this elicited from the middle-aged female audience. They screamed, cried, and threw room keys at Jones’ feet. Sometimes, they would jump up, rip off their panties, and fling them at him.

Elvis professed admiration for Jones’ vocal skills, telling an aide, “Tom is the only man who has ever come anywhere close to the way I sing.” In truth, it was his visceral connection with the audience that wowed Elvis.

He had studied karate for several years, and was a second-degree black belt. He replaced the jerky undulations of his old act with the fluid movements of the martial arts. Backing The King was a 35-piece orchestra, his old five-piece rock band and two soul and gospel groups, the Imperials and the Sweet Inspirations — 50 artists in all.

Opening night at the International, July 26, 1969, was a VIP event. The music press had been flown in from New York and the rest of the country on Kirk Kerkorian’s private jet.

With the band blaring, Elvis took to the stage, and launched into the loudest and most elaborate arrangement of “Blue Suede Shoes” ever heard. He sauntered along the stage apron, kissing one woman after another, wisecracking, passing out sweaty handkerchiefs, singing louder, moving faster, driving the energy level of the show to a goose-pimply crescendo. When it was over, he had won over the thirtysomethings and the media. For the second time in his life, he was an overnight superstar.

The next day, the Colonel sat down with Alex Shoofey in the showroom. Shoofey wanted Elvis for the long haul.

“I’d like to draw up a new agreement with you — for five years,” said Shoofey. The Colonel feigned disinterest, but signed. For the next five years, Elvis would appear for four weeks twice a year at a salary of $125,000 per week. Shoofey walked away amazed, calling it “the best deal ever made in this town.” Even that was an understatement. Showrooms at the time were expected to lose money, which was theoretically recovered in the casino. But by the time Elvis concluded his first month-long engagement, the showroom had generated more than $2 million. It was the first time a Las Vegas resort ever had profited from an entertainer.

So why did Colonel Tom Parker, known as one of the sharpest and greediest men in showbiz, sell his hot “new” act for such a piddling sum? The answer is that Parker, a degenerate gambler, had found a home and planned to settle in. He was housed in luxury, fed gourmet fare and traveled in hotel limousines and planes. Best of all, he had unlimited credit in the casino, where he lost $50,000 to $75,000 nearly every night. He was the highest roller in town.

In his first two years at the International, Elvis’ enthusiasm for his new career kept him happy and busy, experimenting, tweaking his act. In February 1970, perhaps inspired by fashion tips from Liberace, Elvis came onstage in the famous white jumpsuit. It was adorned with long ropes of pearls, beads and rhinestones, as well as a belt buckle of sufficient size to hide his burgeoning belly.

His weight gain was a symptom of a graver problem — boredom. Elvis’ antidotes of choice for this malady were teen-aged girls, fatty foods and vast quantities of powerful pharmaceuticals, most from the Landmark Pharmacy across the street. Dozens of pill bottles bore the names of “The Guys,” old redneck pals Elvis kept on the payroll as aides. Each man wore the logo of Elvis’ “Memphis Mafia,” a necklace with a gold lightning bolt, and the acronym, “TCB,” for “Taking Care of Business.”

While Elvis was onstage, The Guys would be doing just that, combing the hotel and environs, inviting attractive girls to join Elvis in the penthouse for an after-show party.

The handfuls of pills Elvis had taken earlier usually would knock him out in minutes.

Elvis Presley’s drug use probably began about the same time as his career in the 1950s. Racing from roadhouse gigs to county fairs for weeks and months on end, surviving on back-seat naps, he almost certainly discovered amphetamines. A chronic insomniac plagued by nightmares, Elvis had a legitimate need for sleeping pills.

At some point, Elvis discovered The Book, which he would memorize and carry with him for the rest of his life. It was “The Physician’s Desk Reference,” which describes the chemistry, effects and proper use of every U.S.-made prescription drug.

The King liked his medication, as he called it, but feared and despised pot smokers, acid heads and especially, filthy lowlife junkies.

He paid a visit to President Richard Nixon in October 1970 to offer his celebrity as a weapon in the war on drugs.

Stoned out if his mind, Elvis was escorted to the Oval Office, where he rambled at length about the scourge of drug addiction, before coming to the point. He wanted the badge of a federal Drug Enforcement Administration officer, and Nixon gave him one. It was his greatest treasure, and thereafter, he would always carry it. The DEA badge was placed in the drawer below the one filled with his medication.

Supported by dozens of pliable doctors, Elvis’ periods of isolation at Graceland became longer, more frequent. Reviving him and preparing him for his two yearly Las Vegas gigs became a week-long ordeal. And Elvis’ increased drug use had made him more paranoid than usual. The Sharon Tate-LaBianca murders shook him badly, and he saw attackers everywhere — one night even in the International Showroom.

During a performance, a man draped a jacket across his arm, hopped up on the table and stepped onto the stage. Security rushed him and others from the audience joined the melee. As a dogpile rose at center stage, Elvis stood safely to one side, in a karate fighting stance. “Let ’em go,” he yelled. “Let ’em go.”

When the stage had been cleared, Elvis assured the audience that had he entered the fray, he would have “kicked their asses.” The man turned out to be a porno moviemaker from Lima, Peru, who wanted to present Elvis with a jacket.

Guns, Elvis decided, were the key to security. He figured that if he armed himself and everyone around him, he would be safe.

In all, Elvis had more than 250 firearms, and probably gave away as many. In 1970 alone, he spent $19,792 on guns, usually on the basis of how they looked. Gold plating fired him up. So did fancy engraving and custom grips.

One night, in a drug-stoked rage, he fished an M-16 rifle from the closet, handed it to security man Red West and ordered him to go to Los Angeles and kill a man. His target was Mike Stone, a famed karate master, with whom Priscilla Presley had been having an affair since 1968.

Elvis’ wife was profoundly frustrated. Lisa Marie had been conceived almost immediately after their wedding, and Elvis never touched Priscilla again. In the Elvis ethos, women who gave birth were mothers, and Elvis was appalled at the idea of carnality with such exalted creatures.

Elvis rescinded the contract on Stone the next time he got straight, much to Red’s relief. But the couple divorced in October 1973. Elvis, the man who never lost, had lost. He became even crazier.

The end came on Aug. 16, 1977, when Elvis was found dead in his bathroom. An autopsy revealed 11 different narcotics in his body, any one of which could have been lethal in a large dose. The official cause of death was listed as cardiac arrythmia.

Meanwhile, back in Vegas, The Colonel was “Taking Care of Business,” preparing to pick the bones of “his Boy,” with various post-Elvis merchandising schemes, which continue today to make money for the Presley estate.

In fact, during the three years following Elvis’ death, his name and image earned some $20 million, the most lucrative period in his career.