‘You are your brain’: UNLV study analyzes how we experience time

Maybe people can control time — or their perception of it, anyway.

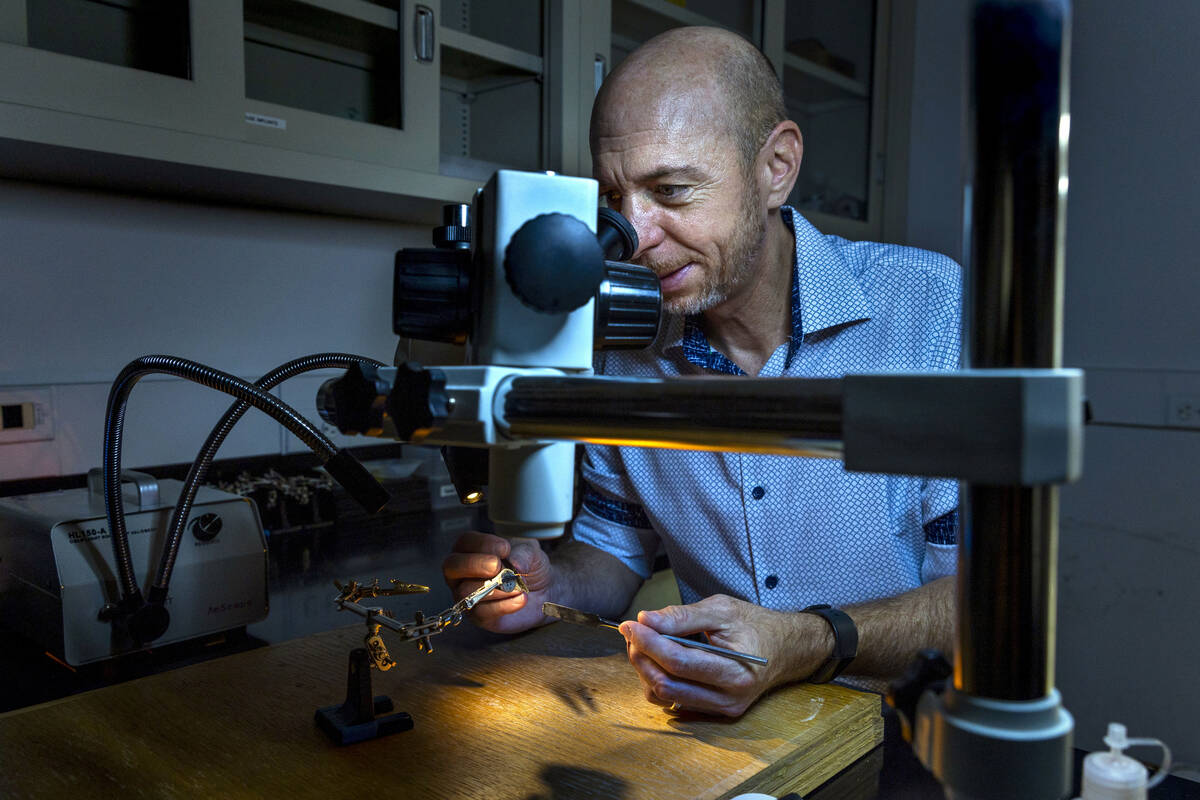

A new paper written by UNLV professor of psychology James Hyman and published recently in Current Biology shows that the way people experience time has less to do with the physical hands of a clock and more to do with the number of experiences in that given period of time.

“You are your brain, and so by taking active control of those processes, you are not only affecting what you’re currently doing, but you’ll affect how you’ve perceived things that happened in the weeks past, and likely in the future as well,” Hyman told the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

The study is among the first of its kind to examine time at the minute and hour level, as opposed to studies that look at it long term, or by seconds.

“Which is how we live much of our life: one hour at a time,” Hyman said in UNLV’s news release.

Behavioral scientist Aaron Sackett told the Review-Journal that the study is the best cellular-level evidence that he had seen for the malleability of time perception. Sackett was an author of the 2010 study “You’re Having Fun When Time Flies: The Hedonic Consequences of Subjective Time Progression.”

“I think that one of the most interesting takeaways is that the study provides support — at the neurological level — that there is no such thing as a fixed ‘internal clock’ that operates independently of sensory input,” Sackett wrote in an email to the Review-Journal.

Hyman’s study also sheds light on an area of the brain related to neurogenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s and may have implications in treating the disorder and others.

The study finds that each time someone repeats an action, brain activity changes. The findings go against the prior notion that the brain responds similarly with repetitive experiences, Hyman told the Review-Journal.

Take an activity like checking email, which many people do several times a day. Despite it being a routine act, brain activity changes with each repetition. The brain, then, tells time based on how many times a person checks their email, not the analog clock outside.

“We know how the pace of life usually is. If we artificially start manipulating on our own, like over-checking our email, that’s going to make it seem like the pace of life is changed,” Hyman said.

The findings suggest people have some degree of control over how they experience time.

When it comes to studying for a test, for instance, Hyman said people might not want to do more activities that could change their brain activity.

“I tell my students to study for 20 minutes and then just zone out,” Hyman said. “If you want to remember the very last thing, you don’t want it to change.”

On the flip side, people who have had a negative experience, like a breakup, may want to flood their brain with activity.

“It’s speculative, but we’re at the point where we’re starting to understand how the brain encodes those different phenomena, and for people to be proactive about how they approach their own brain activity, as opposed to feeling passive,” Hyman said.

The study also has implications for a part of the brain known as the anterior cingulate cortex, which is important for understanding brain disorders from anxiety to Alzheimer’s.

Lila Davachi, a professor of psychology at Columbia University who specializes in memory, said that the study’s focus on the brain region helps understand how it, along with the hippocampus and other frontal regions, helps organize sequential experiences.

Michael Hasselmo, the director of the center for systems of neuroscience at Boston University, told the Review-Journal that the research on this brain region, as opposed to prior studies that focus on the hippocampus, is critical in the understanding of episodic memory — memories involving specific places and times in a person’s life.

“It’s the frontal cortex that kind of helps you think about, you know, what are the cues and what is the correct memory that you’re retrieving for a particular event?” he said.

It holds particular relevance to Alzheimer’s, which is characterized by losing a sense of episodic time.

“It opens up the possibility that we might be able to treat people’s perception of time, train them to be more accurate at how they perceive time, which could, in turn, be able to help with other symptoms as well. It offers some new targets, not only to examine these disorders, but potentially to treat them as well,” Hyman said.

Contact Katie Futterman at kfutterman@reviewjournal.com.