Women underrepresented in top Clark County School District jobs

A former superintendent. A graduate of the old Las Vegas High School. A future governor of Nevada.

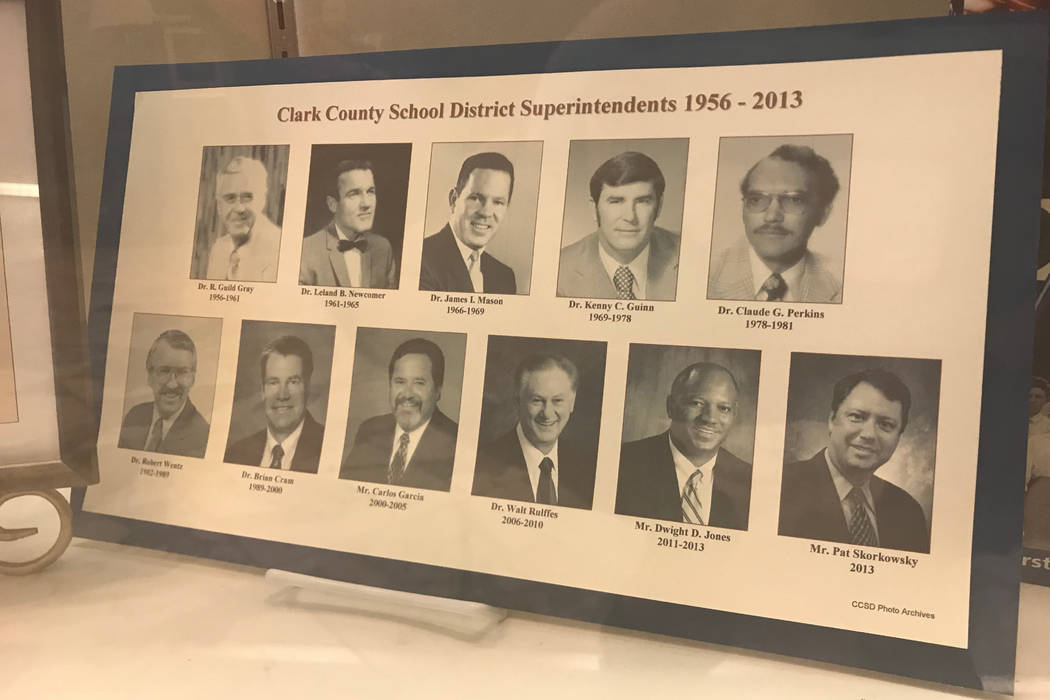

The 11 superintendents who have run the Clark County School District over its 62-year history have brought varied qualifications and personalities to the district’s helm.

All had at least one thing in common, though: They were men.

Although women make up a majority of the district’s teachers and principals, that numerical edge thins to a minority when it comes to leadership positions like assistant or associate superintendent and department chief. And the district — among the largest in the nation — has never had a woman in its top role.

That could weigh on the minds of School Board members as they search for a new superintendent this spring, although board members say they’re looking for the best candidate rather than trying to check a diversity box.

“I think, ultimately, my decision wouldn’t necessarily come down to those demographics, but it would come down to who I feel is the best pick for the job,” said Trustee Lola Brooks.

Fewer women at top

The fact that a woman has never held the district’s top job is not unusual.

In the latest salary and benefits study from the national School Superintendents Association, 22.5 percent of 1,172 respondents identified themselves as female.

But in the Clark County School District, women still hold 64 percent of all administrative positions, including the district’s second-in-command, Deputy Superintendent Kim Wooden.

There’s also an interesting historical exception to the rule: Before the Clark County School District was consolidated in 1956, a woman — Maude Frazier — served as head of what was then known as the Las Vegas Union School District.

Andre Long, the district’s chief human resources officer, said his department is mindful of the status quo and emphasizes diversity in hiring.

“We’re really looking at ensuring that we have diversity, whether it’s gender and whether it’s ethnicity and age,” he said.

For administrative hires in the central office, the department assembles a diverse panel of employees to interview applicants, Long said. The department also asks other employees for input on the panel makeup, asking them to consider diversity.

In hires the department doesn’t directly control, it still tries to make sure there’s a diverse pool of candidates to choose from, Long said. Overall, it is looking for the best candidate with diversity still in mind.

Picture improving

Research suggests that females have made strides in landing superintendent posts — from just 1.2 percent in 1971 to 13.2 percent in 2000, according to one 2003 paper.

It’s an improvement that Margaret Grogan, dean of the Attallah College of Educational Studies at Chapman University, has seen as she’s studied the topic for over 20 years.

She said women were not considered qualified for the superintendency for a long time because they came through the instructional ranks, and not through positions such as head of personnel or the budget.

“Traditionally, when school boards were looking for superintendents, they wanted people who had those kind of experiences,” Grogan said.

But the No Child Left Behind Act in 2002, which put new emphasis on improving educational outcomes, helped change the equation, she said. Districts began looking for superintendents who knew the instructional side of the industry more than the business end.

Aside from increasing opportunity, encouragement and mentorship also are key, according to women who have made the leap to the top office.

Raquel Reedy, superintendent of Albuquerque Public Schools in New Mexico, started in the district as a special education teacher in 1977. She attributes much of her success to having a mentor who encouraged her to take administrative classes.

“Back then, elementary school principals were almost all male,” she said. “But there was a principal who saw something in me and really encouraged me and felt that I could do well with that kind of challenge.”

Cindy Stevenson, former superintendent for Jefferson County Public Schools in Colorado, also credited wonderful mentors who helped move her into leadership roles.

“It was not something I had planned on,” said Stevenson, now interim superintendent of the Boulder Valley School District. “When the board met with me and asked me to take the job, I kept thinking, ‘There must be somebody standing behind me.’”

Part of the issue is the willingness of school boards to hire females, she noted. Another obstacle is having children — Stevenson has cats instead.

She also noted that there tends to be more male high-school principals, a job that is often a pathway to the superintendency.

CCSD superintendent search

Gary Ray of Ray and Associates, the firm conducting Clark County’s superintendent search, said it has placed many females in top school district spots. The firm just helped Nebraska’s Omaha Public Schools select Cheryl Logan as the next superintendent.

The applicants for any given job can vary, depending on the location and challenges, he said. The firm is still focused on bringing the best candidates forward.

“Will there probably be some female and minorities in there? My guess would probably be yes,” he said of Clark County’s potential candidate pool.

In the future, Trustee Linda Cavazos suggests better mentoring and training for female candidates.

“I don’t think that we’re mentoring our females to want to aspire to the superintendency. … It’s like we’re not grooming a pool of women candidates to choose from,” she said.

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.