Pandemic forces CCSD into real-world class size experiment

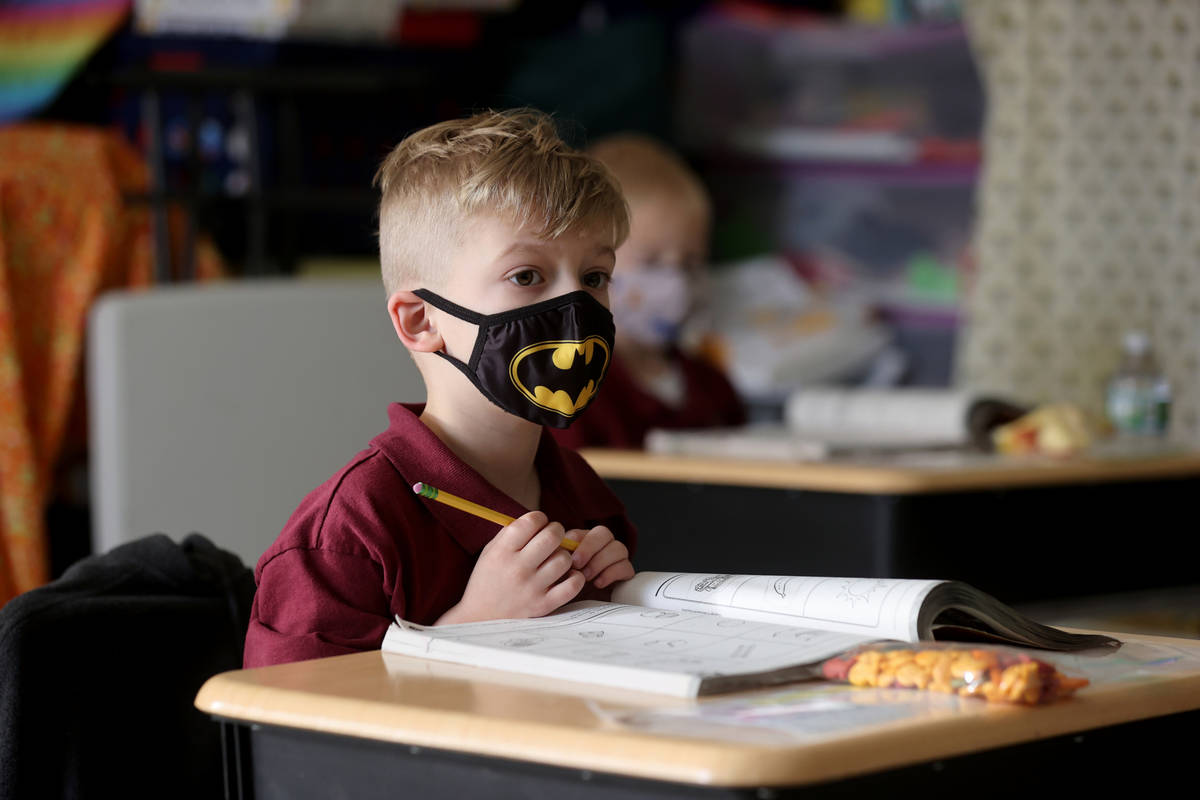

Of the many changes teachers and administrators have seen at Clark County School District schools this spring, the most dramatic is the sparse student populations that returned to campuses as they reopened.

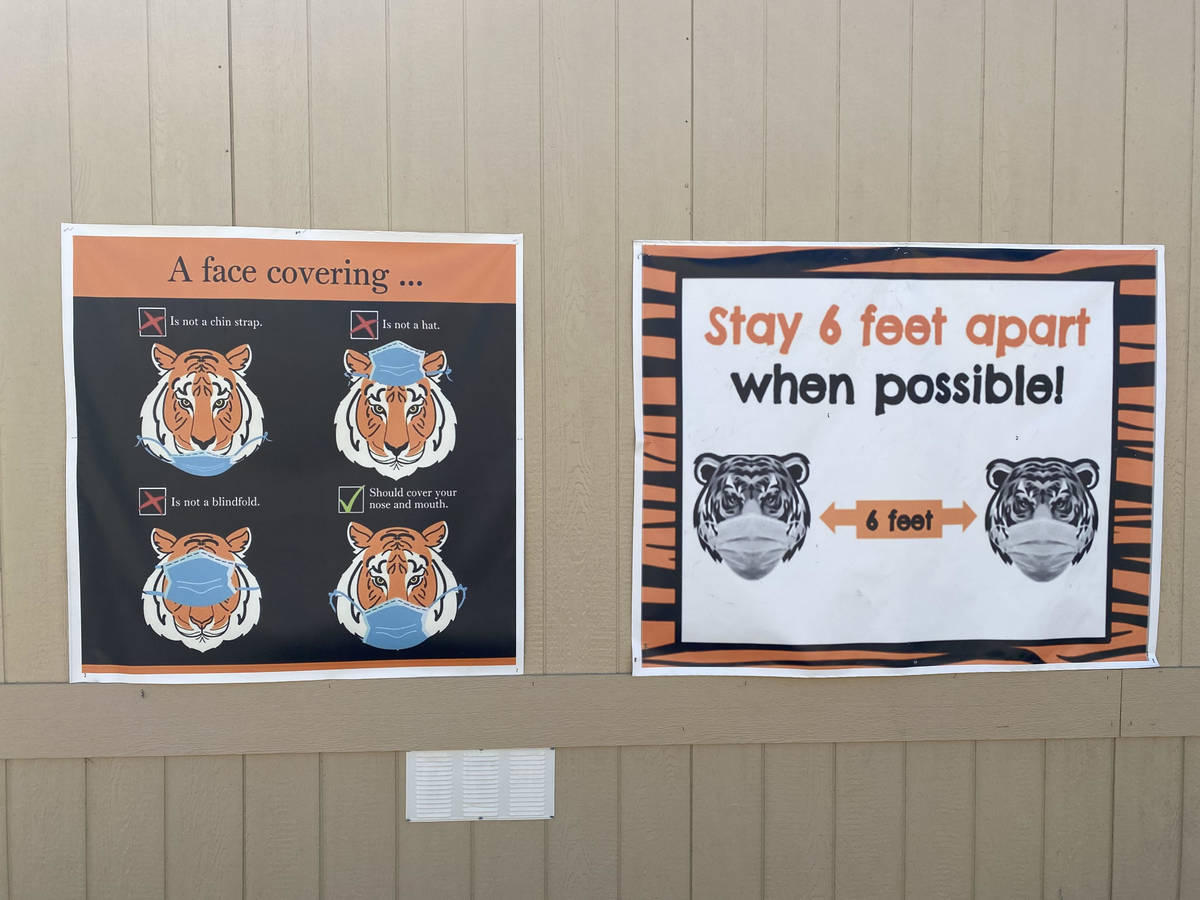

Usually set up for hundreds or thousands of students, most schools welcomed back less than half of their normal numbers starting in March, mainly because of state social distancing guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic and decisions by parents to keep their kids in distance learning.

The result — for a brief, shining moment at least — is the smaller in-person classes that education advocates and many lawmakers have long championed in the state.

But with just four weeks of hybrid instruction at the elementary level before doors reopen on Tuesday to more students, the real-world experiment will largely be over as more students return to the classroom.

And many of those hoping for a permanent shift to lower student-to-teacher ratios say they expect a return to the status quo in the fall.

Decades of advocacy

“It’s setting everybody up for failure,” said Alison Turner, the Nevada PTA’s vice president for advocacy.

Education advocates have been calling for Nevada to reduce class sizes for decades, but rapid growth, insufficient funding and an ongoing teacher shortage have set the efforts back, according to Turner, who also sits on the board of directors for the National PTA but emphasized she was speaking only for herself.

The Legislature passed the first class-size reduction initiatives in the state 30 years ago, but exemptions have been granted each year as districts struggled to meet the targets. A widely shared 2018 study found that despite the efforts, Nevada had the largest average class sizes in the nation.

More recent efforts are showing some promise, however, with a newer study linking the class-size reduction investments to academic gains.

Turner said her children took classes with upward of 40 students in CCSD schools: Her son once took an honors algebra 2 class with 50.

“It was one of the strongest subject areas he had, and he wasn’t getting it,” Turner said. “It just wasn’t possible for this teacher to convey the curriculum.”

No room for backpacks

Clark County’s explosive growth has made the situation even worse, Turner said, as did statewide cuts after the 2008 recession that affected funding for building and maintaining schools, the effects of which are still being felt today.

“Prior to the pandemic, we had classrooms where students couldn’t bring backpacks into the classroom because there wasn’t enough room,” Turner said.

It’s possible that the smaller in-person classes prompted by the pandemic have had a positive effect on some students, Turner said, but it would be hard to quantify.

Context matters, she noted: Elementary students are returning to in-person instruction after a year of virtual learning and will need to spend part of their limited time just learning the procedures for in-person instruction.

And their teachers may be splitting their time between teaching both in-person and virtual classes, making the reduction of students in the classroom largely superficial.

Turner said it’s also possible that some of the benefits of small classes level off at too-small populations. Just 12 or fewer students in a class, for example, may not be enough to facilitate projects or group discussions, she said.

For real long-term gains, Turner said she would like to see the state commit to restoring the cuts of the last recession and then turn an eye to meeting national funding averages and optimal funding targets.

Expanding university teacher preparation programs in Nevada also could help address the teacher shortage, she said.

Teacher shortage

A recent Data Insight Partners presentation to the Nevada Board of Education said that the state is around 3,000 teachers short of meeting its target pupil-to-teacher ratios for grades one through five and secondary core classes, at an annual cost of $260 million.

To meet national staffing averages, Nevada would need nearly 10,000 more teachers to the tune of $800 million, the report estimated.

Clark County schools are in a similar position, with 479 vacant teaching positions, representing about 2 percent of total jobs.

District officials cited three primary challenges in a report to the Nevada Department of Education in reducing class sizes: physical classroom space, difficulty hiring enough teachers and funding.

Even if the district was able to hire enough teachers and supply the necessary classroom space, allocated class size reduction funding from the state “would not cover the salaries and benefits at current levels,” according to the report.

Data Insight co-founder Nathan Trenholm said the teacher shortage is by far the biggest hurdle, made worse by not only an aging teacher population on the verge of retirement but a shrinking pipeline of college students in teacher preparation programs.

Over the last decade, the number of graduates of teacher preparation programs in the U.S. has dropped by 30 percent, according to Data Insight’s presentation. Nevada relies on these out-of-state programs to supply more than 60 percent of its new teachers, with CCSD specifically citing the declining rates of graduates from California as a hurdle to reducing class sizes in the NDE report.

“You can build more buildings, but if you don’t have more teachers, you’re just going to have empty classrooms,” Trenholm said.

But it’s not just number of bodies in the room, he continued: The link between smaller class sizes and improved student success relies on an experienced and effective teacher, and such instructors are likely to be affected by the burnout of having large classes.

Literacy program bears fruit

“If we know a highly effective teacher is going to have the biggest impact on student achievement, we need to look at what the workload is that we’re putting on highly effective teachers to ensure we’re retaining them,” Trenholm said.

To measure the effects of the state’s past class-size reduction efforts, Data Insight looked at a slate of programs targeting literacy that included funding for smaller class sizes.

Since 2014, it found, those programs have produced steady academic gains: By 2019, fourth graders who had benefited from the programs since kindergarten performed on par with their national peers on reading assessments for the first time, according to the presentation.

Could some of those gains be replicable in the short amount of time this semester with smaller in-person classes?

Trenholm said he is hopeful they can. But the pressures of hybrid learning could also lead to more teachers leaving the profession, though it may not become apparent until economic conditions improve, he said.

Distance learning could help shrink in-person class sizes if there are dedicated online teachers, but Trenholm said he doesn’t believe it’s the solution.

“Something is fundamentally broken that people don’t want to be teachers and don’t want to stay teachers. And putting kids online won’t solve that,” he said.

Trenholm would rather see greater investments in education, and smaller changes aimed at improving teacher morale, workloads and retention, like reducing the paperwork associated with most academic achievement legislation.

“But it’s hard to hand over $100 million and trust it’ll be spent the right way without that,” he said.

Grow-your-own

Some solutions suggest schools look beyond university teaching programs to recruit teachers.

One such idea comes from Ronnow Elementary Principal Michelee Cruz-Crawford, who designed a pathway for district support staffers to become teachers. The program works by easing some of the financial barriers to licensure, like the need to take time off work to gain in-classroom experience.

For many staffers, this could be as simple as earning teaching experience for work they’re already doing as aides and paraprofessionals, rather than leaving their jobs temporarily to student-teach, she said.

Some may need other kinds of financial support — for emergencies or child care that might prevent them from attending class — which Cruz-Crawford hopes to provide through a pot of grant money.

After fleshing out the initiative with the Public Education Foundation, Cruz-Crawford sent an email to district support staffers that generated 1,500 responses from people interested in the program. Around 800 of them will make up the initial cohort, supported by 16 administrators from around the district over the next three to four years of the program.

The goal is not strictly class-size reduction, though Cruz-Crawford said that could be an obvious benefit. Instead, she said the mission is to bring more racial and ethnic diversity to the teacher pipeline, while filling vacant teaching positions with people who live in the communities around their schools.

“We wouldn’t have that retention issue that we have with out-of-state hires,” she said. “Having been in a school, (support staff) also have more of that experience than a brand new teacher out of college.”

Cruz-Crawford said her own school has put “every penny available” in federal Title 1 funding for schools with high percentages of low-income students toward class-size reduction. As a result, Ronnow typically has 100 percent teacher retention and lower pupil-to-teacher ratios than recommended, she said.

“We are using all of our Title I to pay for people,” Cruz-Crawford said of class sizes.

“We probably have the same problems everyone else does,” she said of retention challenges. “Anything I can do to make things easier on teachers, I will.”

Brief glimpse of possibilities

At Tate Elementary School in Las Vegas, about one-third of preschool through third grade students participated last month in the hybrid model, giving teachers an opportunity to work with smaller groups of students face-to-face, Principal Sarah Popek said.

Tate Elementary set up its hybrid model so teachers who were on campus were only responsible for providing in-person instruction, while other teachers provided instruction for the distance-learning group.

But with the transition to full-time in-person instruction and the return of more students starting Tuesday, teachers will have “very close” to pre-pandemic class sizes, Popek said, with about 21 or 22 students per teacher expected in kindergarten through third grades and 27 in fourth grade.

The class-size ratio is expected to drop in fifth grade to about 22 to 1 because the school also uses Title 1 funds to pay for more staff than the school district allocation covers.

Tate Elementary expects to have roughly half its student body attending full-time in-person classes — including around 49 percent of students in fourth and fifth grades, two grade levels that haven’t been on campus in more than a year.

More preschool through third graders who previously opted for full distance education are also planning to come back in person.

“We had a considerable amount of students in each of those grade levels that once we went to a full-time in-person learning model, they were on board,” Popek said.

Others may be slower to return. Some students are likely to remain at home until a vaccine is available to children, leaving their classes slightly smaller than before the pandemic.

What no one knows is whether the benefits of the district’s experiment with smaller classes change anything for students who return after its brief run ended.

“Is class size in the spring of 2021 a game changer? It’s hard to predict,” said Turner, the PTA official. “(But) any time face to face in the classroom has to be helpful to kids whose lives have been disrupted.”

Contact Aleksandra Appleton at 702-383-0218 or aappleton@reviewjournal.com. Follow @aleksappleton on Twitter.Review-Journal staff writer Julie Wootton-Greener contributed to this report.