One student’s story highlights Clark County schools’ struggle with violence

This is the first installment in a series, Year in the Life, which will follow one CCSD senior through to graduation — highlighting districtwide issues along the way.

As police arrested D’Andre Burnett at school last year, it hurt to see his mother cry.

Burnett had fought with another student at a park off campus, the continuation of an earlier altercation in which he said his adversary hit him in the face. When he reported to the Arbor View High School office with his mother a short time later, he was arrested for assault and battery.

“I was just more shocked than anything,” he remembered, “because I didn’t know that I was going to go to jail that day.”

The arrest was the biggest bump on what has been a rocky educational journey for the 17-year-old senior. But it was an experience that led him to apply himself at school and try to graduate in the spring.

Burnett’s story is uniquely his, but it also reflects the challenges that thousands of at-risk students in the Clark County School District face as they navigate the perilous reefs of high school. Those challenges can stand in the way of graduation.

And Burnett’s past speaks directly to a major problem faced by the district: reining in school violence.

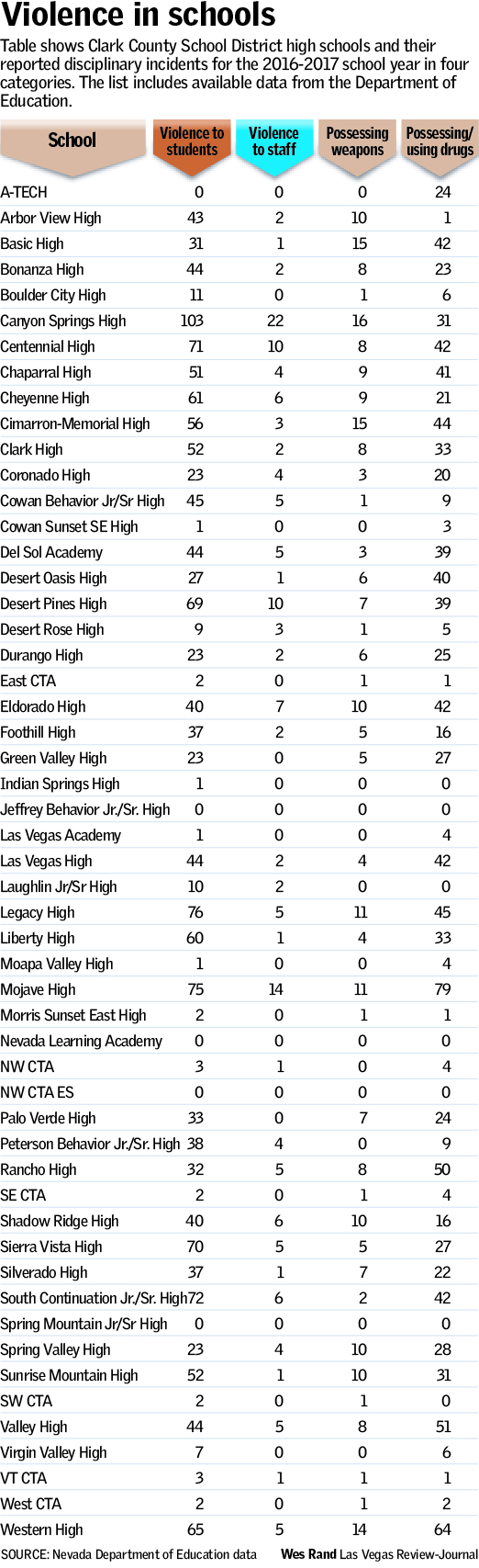

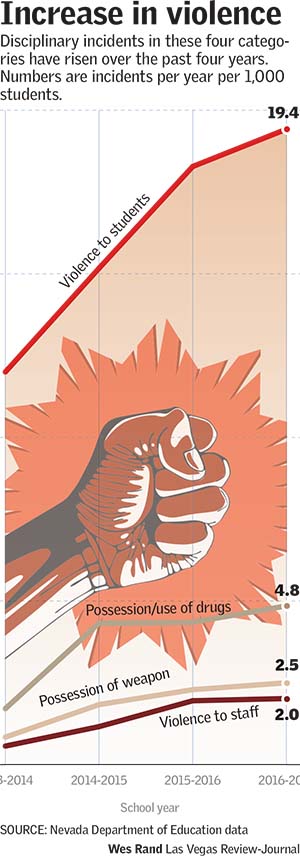

As the district has successfully worked to reduce its expulsion rate over the past four years, it has seen an increase in violence and other incidents requiring disciplinary actions.

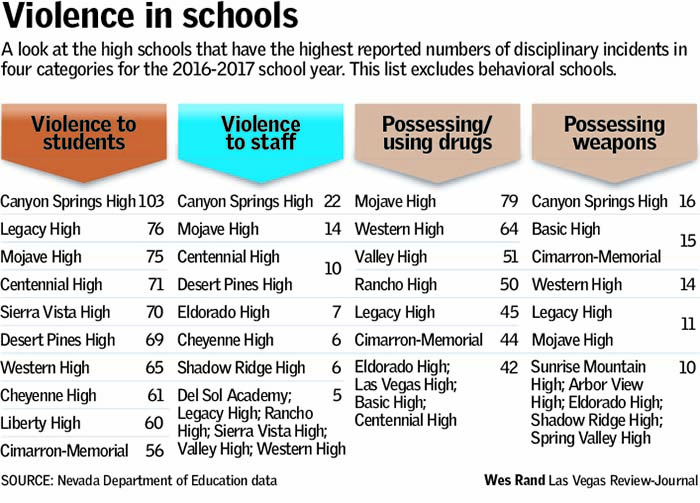

That includes students assaulting students — including three stabbings during this school year — assaulting staff, possessing, using and distributing drugs and bringing weapons to school.

Burnett falls on the lower end of the spectrum. He hasn’t gotten into trouble running with gangs or selling drugs. His run-in with the law — the charge was later dropped — resulted from bad blood with a few other students that built over time.

Yet his story of a second chance highlights the balance the district must strike between expelling dangerous students and not abandoning those who are willing to change.

‘Never been to a school like that’

After the fight that got him arrested, Burnett was sent to South Continuation High School for students with behavioral problems.

Burnett said it was the worst school he ever attended.

There was gang violence, drug trafficking and fights, he said. The scene there is what persuaded Burnett to change his behavior.

“I’m a lot more focused on what I want to do now, because I don’t want to be back in that type of situation,” he said.

Burnett was not welcome back at Arbor View after serving his time at the continuation school under a policy called an “unreturn,” so he switched to the next-closest school, Shadow Ridge.

There, staff have faith that he can graduate despite his current deficit in credits.

“I think he has what it takes, yes,” said his counselor, Natascha Carroll. “He has to believe that, and I think in general he does believe he’ll graduate. But he’s got some bad habits he’s trying to get over.”

While no one begrudges Burnett his opportunity to rebound, some educators say the school district’s efforts to reform a discriminatory expulsion policy are contributing to the violence, which has been growing faster than the overall increase in student population.

On the east side

Eldorado High School Principal David Wilson has seen his share of fights in the eastern valley, which has gang issues. He says he’s even taken a few punches when other student interactions turned physical.

One reason for the increase in violence, Wilson argues, is the district’s push to reduce the number of expulsions.

“By changing what we can expel kids for and giving us (the) directive not to expel students, it has changed our campuses,” said Wilson, who also serves as the president-elect of the school administrators union.

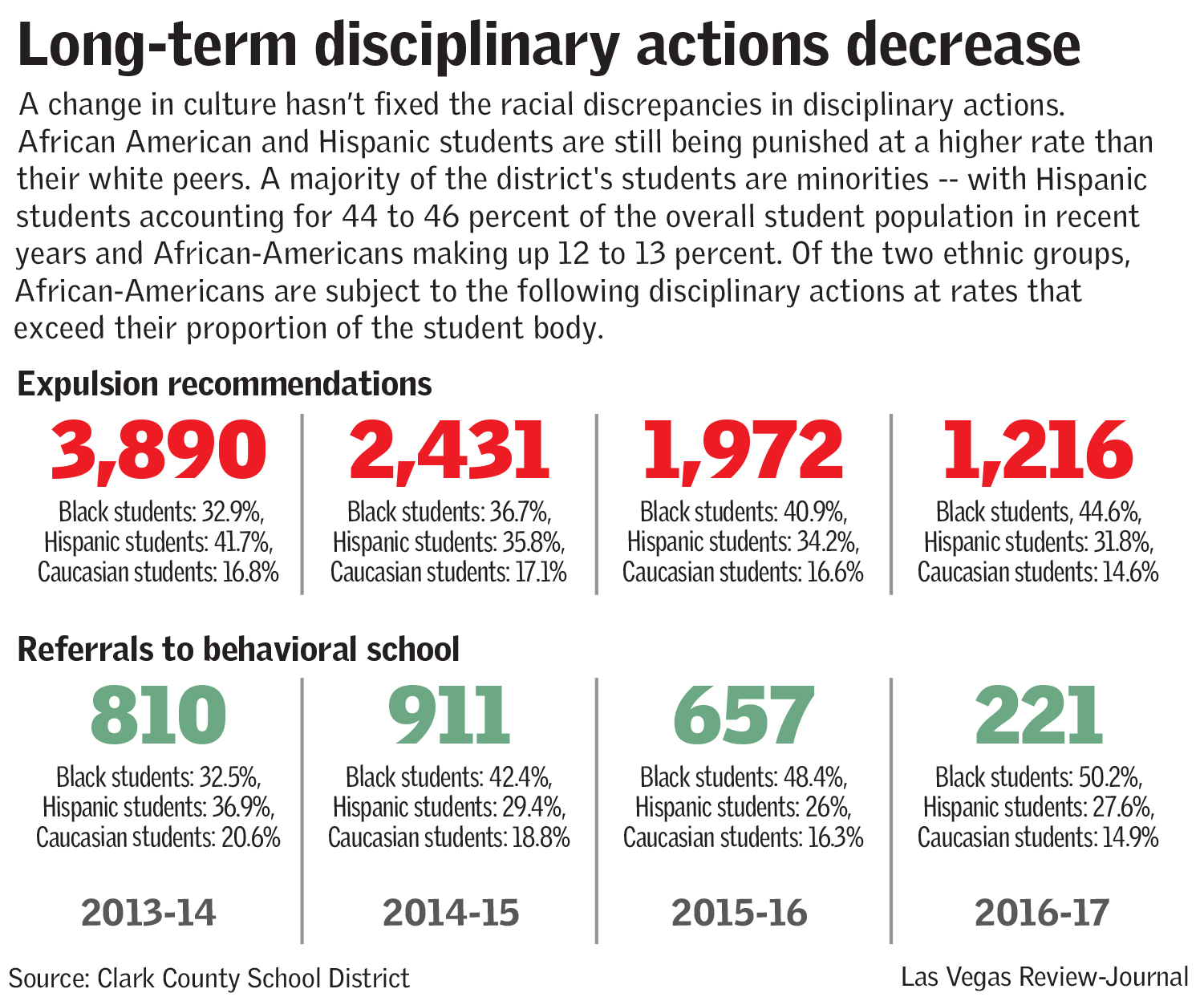

While violence has increased districtwide, the number of expulsion recommendations has decreased nearly 69 percent — from 3,890 in 2013-2014 to 1,216 in 2016-2017. The number of students recommended for behavioral schools like South Continuation High — a “limited expulsion” that allows students to return to regular school campuses — decreased more than 72 percent, from 810 to 221, over the same period.

The problem isn’t confined to schools in tough neighborhoods.

Even at Shadow Ridge — in a suburban corner of the district in the far northwest of the valley — Principal Travis Warnick sees violence and gang activity creeping into his school.

“We have seen an uptick recently in the last year and a half in some of the more aggressive behaviors out of students,” he said. “The same problems they’re facing districtwide, they’re happening here. We’re not different than the rest.”

District officials say they’ve heard the concerns from principals and are seeking solutions. They’re also working to solicit community input, while Trustee Kevin Child has called for a public roundtable on the issue.

“Over the last … couple weeks, the question has been asked: What’s going on? Why are we seeing such a sharp increase in the violence incidents in our schools?” Capt. Ken Young, of the district police department, said at a press conference last month. “We’re asking the same question.”

A change in culture

The district began changing its disciplinary culture around 2013, amid growing community concern over higher expulsion rates for minorities. In 2015, it also faced a complaint filed with the U.S. Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights on the same issue.

The superintendent created an advisory group to find solutions.

One of the changes was the Hope Squared program, which gave money to schools and allowed principals to choose disciplinary alternatives for their school. Some schools chose an in-house behavioral program, STAROn, which allowed disciplined students to attend behavioral courses of study but remain in their school.

The district also ended mandatory expulsion recommendations for certain offenses: Students are no longer booted for assault, arson or having sex on campus.

And in Clark County, expulsion doesn’t always mean a student can never return to his regular school. Limited expulsions — referral to behavioral schools — allow a student to come back after serving time in an alternative setting.

But these disciplinary methods can lead students to conclude there are no real consequences for their actions, Wilson argues. If they’re sent to an in-house program for a behavioral issue, he said, they still get to see their friends.

“At some point, kids have to recognize that there are consequences for their behaviors,” he said. “And in general, that’s not the case.”

The policy shifts haven’t fixed the underlying problem. African American and Hispanic students are still being punished at a higher rate than their white peers. A majority of the district’s students are minorities — with Hispanic students accounting for 44 to 46 percent of the overall student population in recent years and African-Americans making up 12 to 13 percent. Of the two ethnic groups, African-Americans are subject to the following disciplinary actions at rates that exceed their proportion of the student body.

The district counters that it’s the only one in Nevada that expels students for offenses beyond those required by state law.

State law requires suspension or expulsion for battery on a school employee with injury, distributing controlled substances, and possessing a weapon. The district has two other mandatory expellable offenses — battery to students with significant injury and secondary use or possession of drugs and alcohol.

Principals may still choose to recommend expulsion for other actions using their own discretion, although all recommendations are reviewed by the Education Services Division.

District officials also note that Clark County is the only district that doesn’t require schools to take students back who were expelled from their campuses, which enabled Arbor View to reject Burnett.

Understaffed police

Police charged with maintaining order in the district of more than 350 schools offer another explanation: The district’s police department is understaffed.

The force has 143 officers, said Matt Caldwell, president of the Police Officers Association. Proper staffing level would be about 200, he said.

“If we had more officers, we could focus on more preventative things and proactive work, rather than reactive work,” Caldwell said. “Right now we’re really much a reactive police department, due to manpower issues.”

The department announced last month that it would hire eight more officers, after the district has lifted a hiring freeze.

But beyond filling gaps, Caldwell argues the department needs a bigger budget. He estimates that the district spends about 17 cents per day per student each year on an officer.

“That’s not very much money spent on that, and that’s a really big concern for me,” he said.

The district said in a statement that it values school police officers and the presence they have on campus.

“Safety is our number one priority and is always considered as we constantly work to balance the need for school police officers on our campuses with the need to invest in education resources for our classrooms,” the statement said.

‘He better graduate’

Despite concerns over keeping problematic students in schools, D’Andre Burnett is one who has benefited from a second chance.

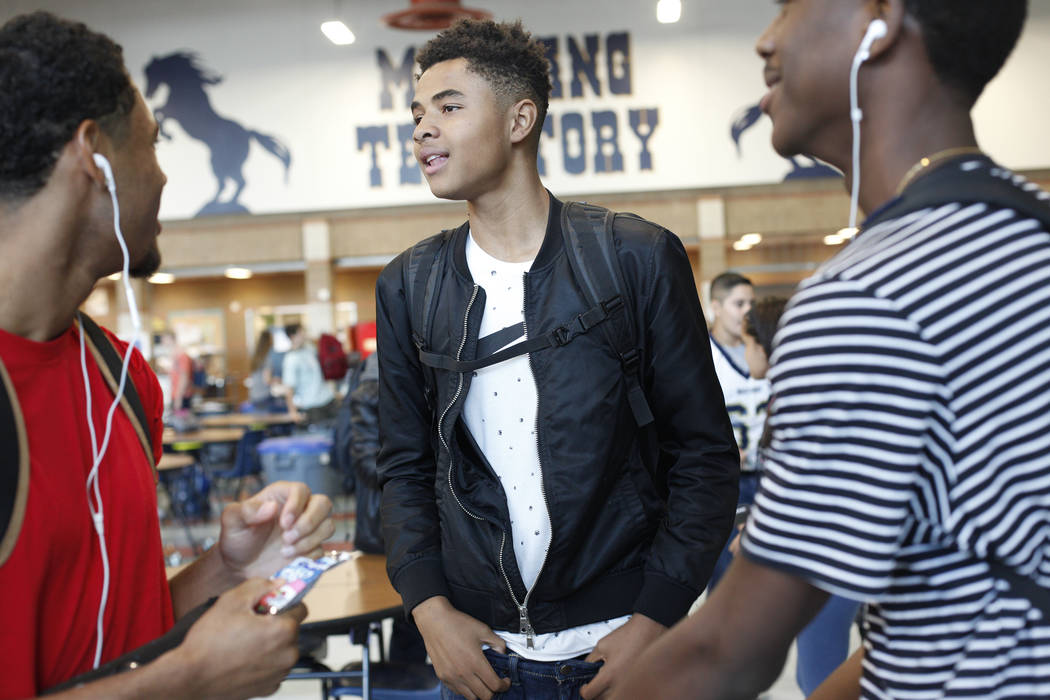

School is good for him so far, he said last month, wearing a blue tuxedo vest and clutching an elegant blue corsage that he planned to present to his girlfriend at Shadow Ridge’s homecoming dance.

“I’m just trying to keep my grades up, and trying to keep my A’s and B’s,” he said.

He’s halfway done with his credit-retrieval class, he said, and he recently took a break from his weekly pre-season basketball practices when he saw his English and geoscience grades slipping.

Along with school staff, his single mother, Brandi Burnett, is keeping a close eye on him.

“He better graduate,” she said. “If I have to drag him across that stage myself, he’s going to graduate.”

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.

Editor’s note: A graphic on an earlier version of this story incorrectly compared the number of disciplinary incidents at West Prep Secondary to those at other Clark County high schools. The statistics were not comparable because they reflect incidents at West Prep’s high school and middle school levels.