Nevada, Clark County gang up to lift underperforming schools

In times of change, Jolene Wallace tries to be a stabilizing force.

The retired Clark County associate superintendent is now a hired gun who serves as the interim principal for schools that have recently entered the Turnaround Zone — a longstanding district initiative aimed at improving the performance of struggling schools.

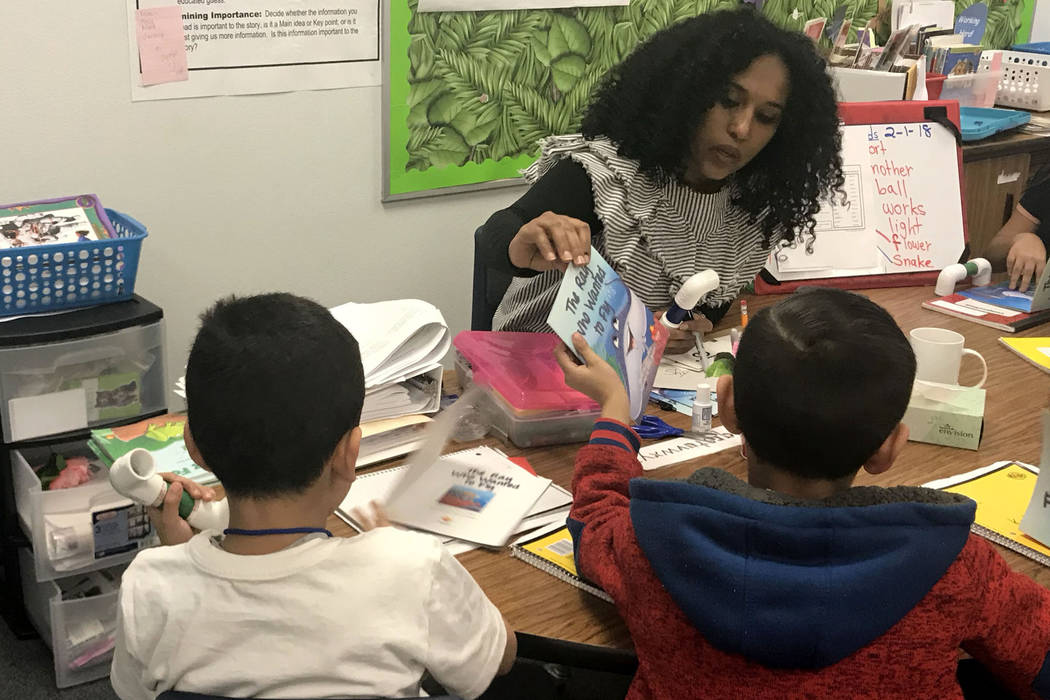

Her latest project is Lynch Elementary, where she is laying the groundwork to enable the school’s newly hired principal to reverse its downward trajectory next school year.

Entering the Turnaround Zone is a scary time for school employees, as the new principal has the power to replace them as a first step toward improving student achievement.

“It’s a very emotional time for employees,” Wallace said. “The question is, ‘Will I be here?’ … I always tell them, ‘Look, you be in charge of your own destiny.’”

But this year the Turnaround Zone, which launched in 2012, isn’t the only effort to improve struggling schools.

Lynch Elementary will also be part of two new state and district initiatives intended to raise its performance, along with those of other poorly performing Clark County schools.

It’s also still eligible for state intervention through the controversial charter school initiative, the Achievement School District. In other words, the school could find itself simultaneously involved in four separate but overlapping efforts to lift it out of the bottom ranks of the county’s roughly 360 schools.

The new initiatives — the School Performance Agreements and Partnership Network — reflect a new cooperative spirit between the Nevada Department of Education and the Clark County School District that has emerged since the achievement district generated considerable angst last school year.

“We saw last year when that all happened with the Achievement School District. It created bad blood,” said Mike Barton, the district’s chief academic officer. “And so I think there were attempts on both sides to repair that relationship.”

School performance agreements

This year, 14 struggling schools entered School Performance Agreements, a local initiative that aims to improve schools in the bottom 5 percent statewide to three-star ratings within three years. Three — Lynch, Johnston Middle and Reed Elementary — are also in the Turnaround Zone.

The agreements are a district-developed alternative to the state’s performance compacts, which would have spared schools from entering the achievement district. The School Board rejected that plan in March 2017, preferring local control.

Under the district’s performance agreements, two associate superintendents visit the schools twice a year. They also monitor schools in nine areas, including assessment, climate, leadership and curriculum.

District officials tout the effort as one that acknowledges the need to address poor-performing schools beyond the Turnaround Zone.

“I think it’s a vehicle to promote a sense of urgency and put a microscope on some of the schools that we need to put a microscope on,” Barton said.

Partnership network

The state and district also plan to pilot a partnership network of 30 schools — including two charter schools that are already a part of the Achievement School District and others on the state’s underperforming Rising Star list.

The network allows high-need schools to share services and ideas for improvement.

That means the schools approach funding differently. They still will apply for the state and federal money they would normally seek — such as federal School Improvement Grants or Title I funds — but officials have developed plans to integrate different types of funding to meet their needs, according to Brett Barley, the state’s deputy superintendent of student achievement.

“The difference is that we sat down with Clark County and we talked about how all those different funding streams could come together to create a comprehensive plan,” Barley said.

The network will also include five nonprofits that will work with schools to boost their achievement.

“I do believe that this is far more healthy, to work in a partnerhsip with the state in that way, than to have this ominous thought of an Achievement School District swooping in and taking the school,” said Jeff Geihs, the district’s associate superintendent over the Turnaround Zone.

‘Strong signal’ to state

Kenneth Wong, director of the urban education policy program at Brown University, said the district’s differentiated approach to school improvement is “an appropriate and well-balanced approach” to address shortcomings, as long as the district provides guidance and clarity to schools so that they know how each initiative applies to their situation.

The district also apparently responded to the threat of a state takeover of struggling schools by developing proactive strategies, Wong said, and having local ownership or responsibility for underperforming schools is important in turning them around.

“I think this is kind of the district’s strong signal to the state that ‘We understand that these schools have to be held accountable,’” he said. “They recognize that, but at the same time they are saying that these will continue to be our schools.”

The initiatives don’t stave off the state achievement district. Three of 10 eligible Clark County schools could still face competition from the three charter operators next school year, regardless of whether or not they enter a performance agreement with the district.

But district officials say they’re taking the school improvement effort seriously.

“I think the state can rest assured, as is evidenced here at Lynch, that the district is taking it most seriously from the performance agreements that our board has had us invoke,” said Geihs, the district’s associate superintendent. “We don’t take any of this lightly.”

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.