Final push lands at-risk Las Vegas student on graduation stage

This is the third and final installment in a series, Year in the Life, which followed one at-risk Clark County School District senior as he works toward graduation — highlighting districtwide issues along the way.

The final months of D’Andre Burnett’s high school career were in turns turbulent, tragic and triumphant.

In January, the 18-year-old was sent to an in-school behavioral program. In April, he witnessed the shooting death of a 16-year-old friend on a Las Vegas street. And on the week of graduation, he faced his mother’s wrath when she learned he apparently was not going to earn his diploma.

That’s how, just one day before graduation, he found himself in a classroom at Shadow Ridge High School with a handful of other students, facing the daunting task of completing work in three online courses by day’s end.

The marathon was the culmination of an all-hands-on-deck effort to raise Burnett’s grades above 60 percent in all his classes so that he could graduate on time at the end of May. The maneuvering included waiving a denial of credit for a physical education course, switching him to a different English class to limit distractions and assigning a behavioral strategist to help him stay focused and finish assignments that had piled up.

If there was ever a time in his troubled high school career to buckle down, this was it.

“Read before you go to bed,” his strategist, Danielle Jones, had told him weeks before as they discussed an English project on Shakespeare. “Not go on Twitter, not on Instagram, not on Snapchat — ‘King Lear.’”

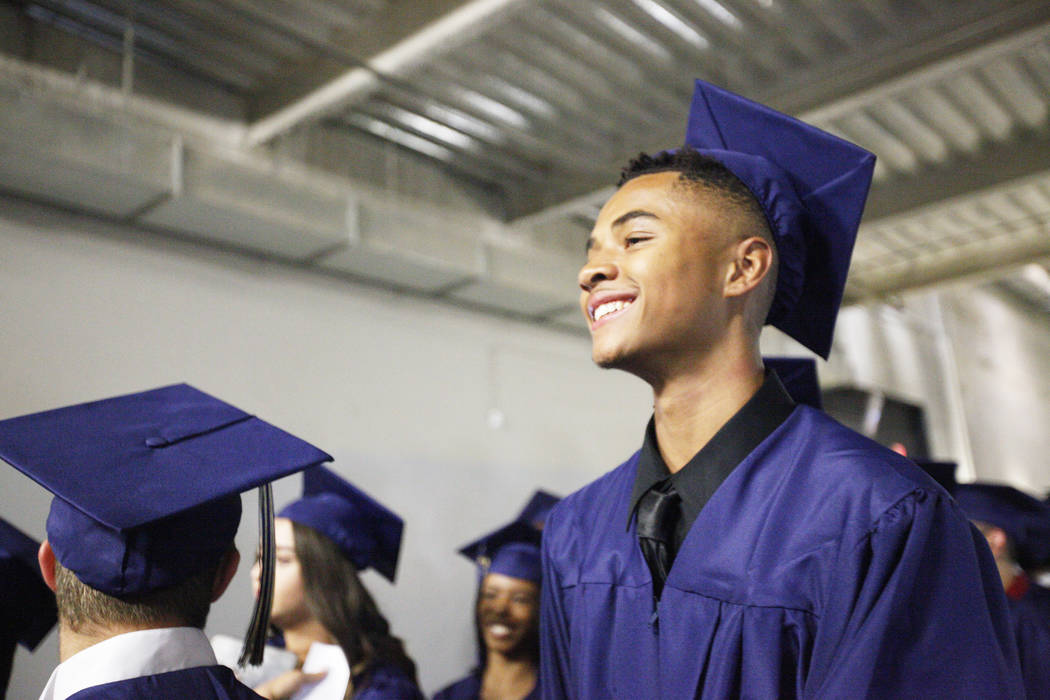

The sustained push and final harrowing hours paid off. Burnett walked the stage on May 24 with the rest of the class of 2018. He was all smiles on graduation day.

“It was more, like, weight off my shoulders more than anything,” he said.

While Burnett’s graduation might prove to be a turning point in his young life, it also raises questions about the Clark County School District’s rising graduation rate — and whether propelling marginal students out the door is doing them any favors.

Barely surviving

The shooting happened on his 18th birthday.

Burnett said he and a group of friends on April 27 were walking back from a McDonald’s in the northwest corner of the Las Vegas Valley when he heard gunshots.

“I thought it was fireworks because it wasn’t like a loud gun … then I heard the bullets whizzing past my head, and I kept running,” he said.

When he returned, he saw classmate Justise Allen on the ground. The 16-year-old girl died in a shooting that police say was targeted and gang-related, and another 19-year-old was injured.

At school, police called Burnett in for questioning.

But he said he didn’t know why the two gunmen climbed out of a car and opened fire on his group of friends. He said he hadn’t been involved in gangs and was just focused on school and basketball.

Police said the investigation was still open as of last week and did not provide any update.

Burnett said the shooting didn’t interfere with his studies. But he acknowledged that it hurt him mentally and said he felt guilty.

“She was down there for me … and she was so young,” he said.

The emotions only added to what already was a difficult situation at school.

In January, Burnett had been sent to StarOn, the district’s in-house behavioral program, which exists as an alternative to suspensions. He and his mother, Brandi Burnett, say he was disciplined for having drug paraphernalia on campus — specifically a lighter, an empty bottle and empty baggies.

D’Andre continued to do his work but fell behind in English.

He acknowledges that his behavior was to blame.

“If I would’ve never went to StarOn, then I would’ve never been in this (mess),” he said, the week before graduation. “I would’ve been in class the whole time, and I would’ve had my grades up the whole time.”

The final push

That was the same week that Burnett’s mother received a call from the school. He had failed English and government.

His counselor, however, gave him one final shot at redemption: recovery of those credits through Apex Learning, the Clark County School District’s online course program. He also later found out he needed to finish another elective course, adding a music appreciation class to his list.

The Apex program helps those who need to make up previously failed classes, offering another gateway to graduation. Yet it also comes with a temptation.

Teachers must unlock access to quizzes and tests, requiring students to take them from school. But for much of the course, there is little to stop students from searching for answers online.

That’s just what Burnett did as he scrambled through the final hours of his senior year.

“That’s what everybody does,” he said.

Jesse Welsh, assistant superintendent of curriculum and professional development, said students shouldn’t be sitting there Googling for answers.

But, he added, the challenge to prevent cheating is the same in any regular class where large numbers of students are taking an exam.

“If the teacher is not being mindful of what’s going on, it’s the same kind of challenges you would have in a regular classroom,” he said.

The online courses also typically have both computer- and teacher-scored tests, Welsh said — so not all answers can be found online.

The district usually uses about 10,000 “seats” in Apex courses of its 12,000 maximum, at a cost of $40 apiece, according to Welsh.

But the online tests and the use of graduation rates as a key accountability metric for schools could contribute to what data shows is a serious lack of preparation shown by many Clark County students.

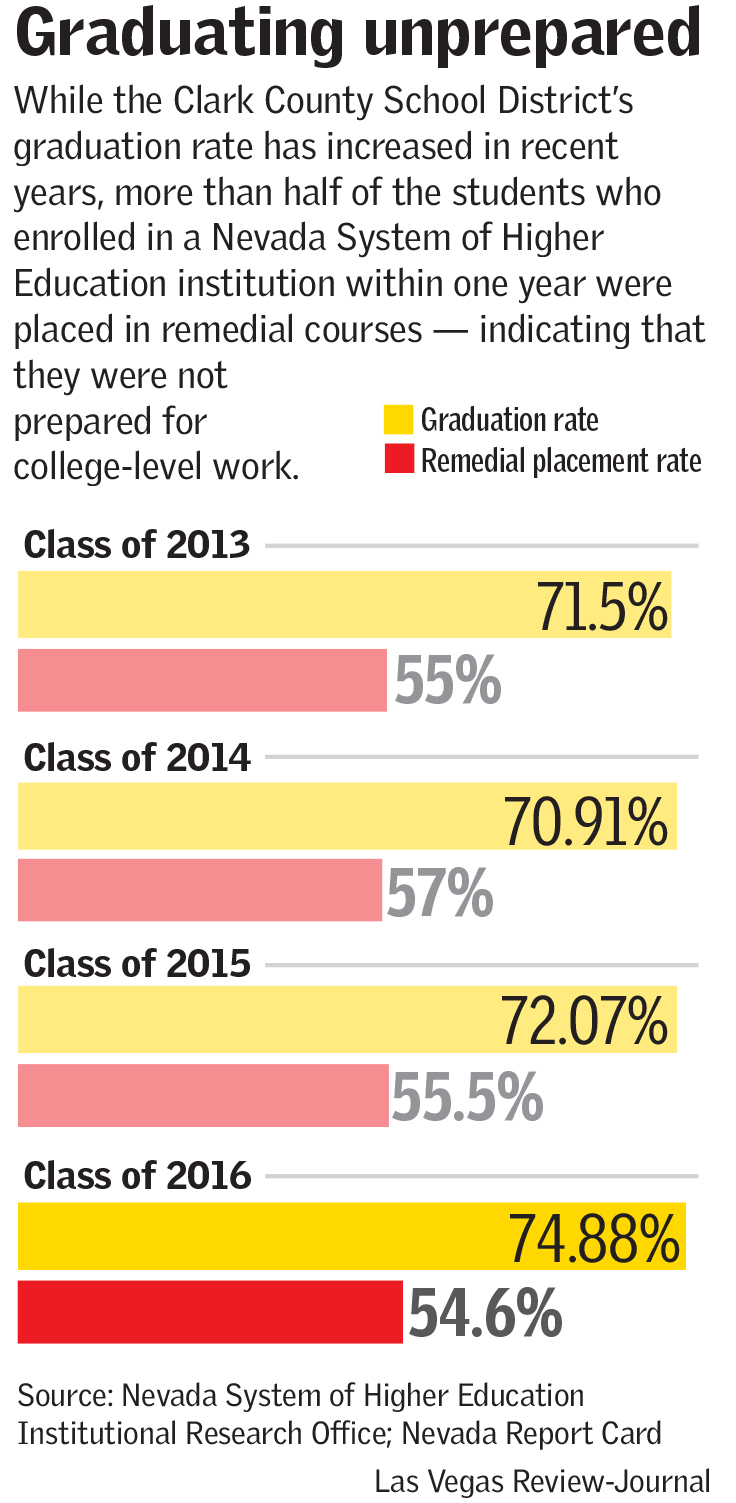

While the district’s graduation rate has increased in recent years, more than half of those students who enroll in a Nevada System of Higher Education institution within one year of graduating are placed in remedial courses. Those courses are intended to address academic deficiencies before students move on to college-level courses that count toward a degree.

Still aiming for college

Despite the eleventh-hour shortcuts he took, Burnett said he’s ready for college-level work.

He is hoping to attend community college and play basketball, and he’s interested in business and marketing. One coach from out of state was coming to look at him play this weekend, he said. If the basketball opportunity doesn’t pan out, he plans to attend the College of Southern Nevada.

His mother went from angry to overjoyed when she found out that he could walk just one day before the graduation ceremony. The family scrambled to make arrangements to attend.

“You should try to get pants the night before graduation,” she said. “Everything was sold out. I didn’t get the cap and gown until that morning.”

She said she cried so much during the ceremony that she couldn’t manage to record it.

The family is still celebrating the diploma, but Brandi Burnett is already looking to the future and thinking of ways to maximize her son’s chances of success in the next step of his academic life.

“D’Andre can do it if D’Andre focuses,” she said. “He’s an excellent writer. I just, I think we’re not going to do any morning classes — we’re going to do it in the afternoon, when he comes alive.”

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.