Don Laughlin

The principal was decidedly upset with young Don Laughlin.

“He said to get out of the gambling business or get out of high school. I couldn’t see what one had to do with the other,” said Laughlin. “But I could see that I was making more money than the principal, so I left school.”

And that’s how Laughlin happens to have an eighth-grade education and enough money to build a small city, which is named for him.

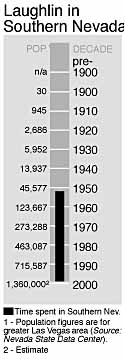

In less than 35 years Laughlin, and other gambling entrepreneurs following his lead, built the town of Laughlin from a bankrupt saloon and motel beside the Colorado River, to one of Nevada’s most important tourist destinations, attracting 4.2 million visitors a year.

Laughlin was born in Owatonna, 50 miles from Minneapolis, and grew up on a farm seven miles from town. His father was a part-time trucker. “I went to a country school where all eight grades were in one room. I must have graduated from there about 1946, the only school I ever graduated from.” He went to high school only a year, meanwhile building up a route of slot machines and punchboards. Then the principal called him in for that chat. “He’s long gone and I don’t hold it against him,” said Laughlin. “He had strong religious convictions and thought he was doing the right thing.”

Most of Minnesota, he notes, did not share those convictions. Punchboards and slot machines weren’t legal but nobody enforced the law. “Every little bar and restaurant had a couple of slot machines. If you took your car to get it repaired the garage had a couple you could play while you waited.”

It was not until 1952, after a federal crackdown on illegal gambling, that Minnesota started tightening up. Laughlin went to Las Vegas for a vacation, and liked what he saw.

Laughlin worked in casinos and, about 1954, bought a beer-and-wine bar at 412 W. Bonanza Road, and, naturally, put in a few slot machines. “Those were segregated days, but Bonanza was an open street, and part of our business was black, and white as well. We never had any trouble. Me and my wife ran it ourselves.”

Only a few months later, Idaho cracked down on gambling, and a refugee operator from that state offered $10,000 for his going operation. “That was a lot of money then,” said Laughlin. It represented a fat profit, so he took it.

He quickly bought another bar in North Las Vegas, the 101 Club on Salt Lake Highway, got a live gaming license, and opened what he said was the only blackjack game in that part of town.

Four years later, in 1959, he bought land across the street from the 101 and built a new joint from the ground up, opening Jan 1, 1960, under the same name. “Business tripled overnight because we had plenty of parking and a nice restaurant.” In 1964 he sold that club for $165,000.

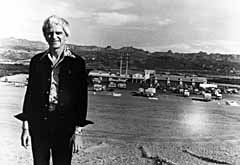

He spent the next year or two learning to fly a small plane, then barnstorming the state looking for a new opportunity. He found it in 1966 — a bankrupt bar on an unpaved road on the Colorado River, in an area then known generally as South Point because it was in the southern corner of the state.

Across the river was Bullhead City, Ariz., a village that had begun as a supply and support base for construction gangs building Davis Dam on the Colorado River. Construction gangs were long gone and Bullhead survived as a laid-back community of bait shops, bars, and affordable travel-trailer parks.

“I wanted a place on a state line because I have always known that a place on a state line gets much higher play than anywhere else,” Laughlin said in 1988. Out of every 10 people who came into his North Las Vegas club, he estimated, nine might be there to drink, eat or hang out, and only one to gamble. “On a state line if 10 people come in, you get nine players and maybe all 10, because being able to gamble is the reason they come here.”

The highway crossing Davis Dam was not heavily used by those coming to Nevada to scratch the gambling itch, but that doorway to Nevada was 25 miles closer to Arizona cities than Hoover Dam was.

He got the motel and six riverfront acres for $35,000 down, on a $235,000 total price. Two years later, when the U.S. Postal Service decided to open a post office on the Nevada side of the river, it named the community Laughlin.

There were eight motel rooms when Laughlin bought it. He and his family lived in four of them, leaving four to rent to the public. By 1972 he expanded his Riverside Resort to 48 rooms; by 1986 to 660. Today he has 1,400 plus 800 recreational vehicle spaces. And eight other hotel operators, seven of them also in the casino business, have moved into his backyard. There are nearly 11,000 rooms in Laughlin today.

Laughlin’s phenomenal growth is partly related to the popularity of the nearby Lake Mead National Recreation Area. The National Park Service resisted efforts by private concessionaires to expand the few motels and snack bars, thus directing most recreational business outside the park.

Some of Laughlin’s advantages were pure luck, but once he drew such fortunate cards, he played them better than others did.

For instance, many Strip hotels were slow to add amenities for recreational vehicles, assuming that couples who drove a car with a built-in kitchen and bedroom were cheapskates who wouldn’t gamble. Laughlin saw them as operators of one-room hotels who handed him all their casino action. “Anybody who owns an RV is somebody with money. We’ve found RV customers spend just as much money as people who stay in our rooms,” he said in 1988. He noted RV spaces then cost about $5,000, while a hotel room would have cost $50,000.

Cheaper infrastructure became a cornerstone of Laughlin’s success, said the town’s namesake. “The prices are cheaper because we’re not in the high rent district. You can still rent a room for $15 or $20 a night, weekdays,” said Laughlin recently. “Of course weekends are much more because everything gets full.”

About 20 percent of the summer crowd, he said, is directly involved in some water sport. “We have our own dock and let people tie up boats, jet skis, and even the occasional float plane there. …

“In the winter the crowd changes. People in (their) 60s, 70s, 80s. We stay packed with them from November to May. They’re all gone after 9 or 10 at night but they’re back first thing in the morning.

“A lot of these stay all winter,” Laughlin added. “Some of them take jobs, maybe three days a week, and we hire them if we can.”

Laughlin’s Riverside has ironed in some wrinkles for each group. For the younger crowd it added a child care facility, which, in defiance of conventional casino wisdom, makes money. And for the older crowd they added afternoon tea dances, which have validated the conventional wisdom by never making a cent. “Dancers don’t give you much action in the casino,” said Laughlin. But he keeps the program partly because he personally enjoys ballroom dancing, and usually participates.

The town of Laughlin boomed like a kettle drum through the 1980s and early ’90s, then went into a four-year decline from 1995 through 1998. Early figures for 1999 show the trend may have been reversed.

Laughlin blamed the decline on Indian gaming. “There are probably about 18 casinos in Arizona and probably 45 or 50 in California …

“But that hasn’t been all bad for us. If we’d kept growing as fast as we were, there would probably be eight or 10 more hotels here.”

The breather has given Clark County and Bullhead City governments a chance to catch up with problems caused by Laughlin’s former runaway growth. County Commissioner Bruce Woodbury said one of the main needs is to get the Bureau of Land Management, which controls most land in the area, to release more for private development. “If we can get it, I would hope some would be used for residential development, including affordable housing, as well as some general commercial development. They don’t yet have a lot of the amenities that make it a community.” Housing in Laughlin is too expensive for most casino workers, who find what they can in Bullhead City.

Don Laughlin has done his part in solving many of those problems. In one famous incident, he built at his personal cost a $4.5 million bridge, bypassing the twisting road across Davis Dam which Laughlin was told had claimed 42 lives in 20 years. “Down here on a state line you’ve got two fish and game departments, two highway departments, and two of everything else,” said Laughlin. “It took four and a half years to get the bridge approved by, I think, 38 different agencies. Only took us four months to build it.”

He admitted, “Of course, this was a position play on our part.” He located the bridge a stone’s throw north of his parking lot, putting his hotel closest to all the traffic that crosses.

Laughlin frankly reveals that such enlightened self-interest was at the bottom of his philanthropy in buying the Bullhead City Airport, then bankrolling a complicated land swap enabling Mohave County, Ariz., to buy public land to make it large enough for commercial jetliners. Laughlin ended up getting some of the land around the airport, with great development potential, and Mohave County ended up getting a modern airport. But his real bottom line, said Laughlin, was to head off a movement to build a new airport somewhere else. He kept it directly across the river and five minutes from his hotel.

But for all his high-level deals, the town of Laughlin is no longer a one-man show. “There’s an active town board with a broad base of citizens,” said Woodbury. “There are people who work in the power plant, people who work in small business. I haven’t seen any reluctance on his part to let the town run itself. He’s a maverick who has his own ideas and likes to carry them out without interference. But if somebody else has a good idea, there’s no jealousy there; he just sees it as bringing more people to the community and giving him a chance to get some of them in his own door.”

Laughlin founded the town’s first bank, but recently sold it. At the age of 68, he explained, he is trying to wind down. However, he still works most of two standard shifts a day in his own casino, starting about 10 a.m., taking a siesta in the early afternoon, then resuming till 3 in the desert morning. “I don’t have to do that, but I enjoy working,” he said. “I don’t play golf or bowl or fish. Don’t even go to many movies, although I can do it for free since we have our own theaters here.”

Laughlin’s oldest son, Dan, 46, is general manager of the Riverside. Another son, Ron, 41, has a restaurant and janitorial supply company headquartered in Bullhead City, but serving clients as far away as Las Vegas. His daughter Erin, 38, recently rejoined the Riverside as a parking valet.

Laughlin is separated from his wife, the former Betty Jones, but the two remain friendly.

In 1987 the magazine Venture, which specialized in articles on entrepreneurs, ran a long cover piece detailing how Laughlin built his empire, and suggesting that the one-man operation would no longer be able to compete against the larger bankrolls of the big corporate competitors from Las Vegas.

Twelve years later, he’s still there, running the hotel that looks busiest of the nine lining the riverbank.

Part III: A City In Full