C.D. Baker

The war in Europe and the Pacific was over by 1951, another had started in Korea, and the battle of Las Vegas was under way. The growth the city had encouraged and nurtured for so many years was threatening to strangle it.

There was a shortage of housing and electricity. A large percentage of the city’s streets were unpaved. The demand for phone service increased daily, and the wait for hookups often ran into months. Nellis Air Force Base had been reactivated, and the Nevada Test Site had just opened. People were pouring into town.

Worst of all, the town was running out of water — fast. Since modern air conditioning was then an expensive indulgence, residents relied on swamp coolers. Problem was, on some days, the water pressure wasn’t strong enough to push water up onto the roof and over the cooler pads. Lawns and gardens died. Deodorant sales soared.

Enter Charles Duncan Baker, combat engineer and mayor of Las Vegas from 1951 to 1959. He would redesign what was essentially a Depression-era city infrastructure and guide Las Vegas through the frantic ’50s and into the modern era.

Baker was an old-style politician, meaning he probably couldn’t get elected in the TV age. When he thought an idea was stupid, he didn’t call it “ill advised,” he called it “stupid.” As a military man, he was used to giving orders, and he was equipped with fine vocal cords, which emitted a sandpapered growl or an arresting bark. The cigar clamped between his teeth rounded out the picture.

Tumultuous city commission meetings were often called to order by the mayor without the use of a gavel.

“Sit down and shut up,” he would roar.

The crusty colonel was born in 1901 in Terre Haute, Ind., the son of a grocer. He graduated from Rose Polytechnical Institute, and went to work for the Indiana Highway Department. Boredom set in, and Baker went to Chicago. It was at an employment agency there that he first heard of Las Vegas. The town needed a high school mathematics teacher and athletics coach.

In 1922, Baker took the job for $1,650 per year.

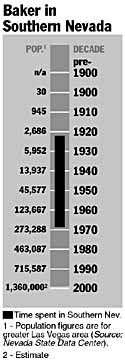

“The population was the same as the altitude posted at the railroad station — 2,034,” Baker recalled in a 1964 interview.

Soon after his arrival, he married a Nevada lady, Florence Goldfield Knox, who was named for the Florence mine in that once-great mining camp.

Still restless, Baker signed on with the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey and spent a year surveying and mapping the Alaska coast. He returned to Las Vegas to start his own engineering company in March 1924. It dovetailed nicely with his other business, real estate speculation. In an advertisement in The Las Vegas Age newspaper in the early 1930s, he asked, “You wouldn’t go to a blacksmith to buy a hat; why not consult a civil engineer when you buy land?”

Baker was appointed city engineer in 1935. He quit in 1938, when he was elected state surveyor-general, a position that no longer exists.

It was during the Depression that Baker’s administrative skills first came to public light.

“God has had his arms around this country,” said Baker, recalling that time, “but in 1933, the hand rested only lightly.”

In May of that year, Baker led 10 young men into Kyle Canyon below Mount Charleston. Baker, representing the U.S. Forest Service, was charged with building a camp to house the “Reforestation Army.” This was one of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, which would eventually be renamed the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC).

Less than two months later, Baker’s boys numbered 212, had completed the camp, started work on trails, recreation areas and water systems, and strung the first telephone line into the canyon.

In 1933 Baker was named engineer-examiner for the Nevada and California Works Progress Administration (WPA), at the lordly salary of $3,300 per year. This made him local liaison with the feds in mapping out and administering public works programs.

Baker was active in the Clark County Democratic Central Committee, which generally dominated local politics, but his first run for the Las Vegas mayor’s chair failed. That was in 1939, against three opponents, Fred O’Donnell, James Down and John Russell. Baker was president of the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce, and his campaign slogan was, “Tourists and Industries or the Same Old Stuff?” His was one of the first campaigns to emphasize the future importance of tourism to Las Vegas, and the need to provide the roads and infrastructure to accommodate them.

Further political plans were delayed by a call in April 1941, to active duty in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Capt. Baker spent the remainder of the year designing and building airstrips in the South Pacific. In November 1941, he was completing an airstrip on Canton Island, a barren coral atoll. His outfit, the 1399th Engineer Construction Battalion, was made up mostly of Hawaiians descended from Japanese. After U.S. forces recovered from the surprise attack of Dec. 7, Baker followed Allied troops in their island-hopping campaign across the South Pacific toward Japan. He built airfields, bases and hospitals on Kwajalein, Guam, Okinawa and in the Marshall Islands. He attained the rank of lieutenant colonel, plus several commendations and decorations.

At war’s end, in 1946, Baker ran successfully for state Senate, serving in the 1947 and 1949 legislative sessions.

With the economic survival of the county at stake, the Clark County delegation of 1947 focused on passing two vital pieces of legislation. The first created the Las Vegas Valley Water District, empowered to buy the dilapidated city water system from the Union Pacific Railroad, gaining control of the valley’s primary underground water source. The other bill authorized the state to negotiate with the federal government for the purchase of Basic Magnesium Inc. in Henderson. It gave the water district access to the only water pipeline from Lake Mead.

Florence Lee Jones and John Cahlan, in “Water, A History of Las Vegas,” pointed out that passing these bills was no small task, since Clark County had only five of the 41 Assembly seats. Like all 17 counties at the time, it had one senator, Baker. Still, H.E. “Hap” Hazard, Baker’s real estate business partner, was speaker of the Assembly, and Las Vegas attorney, judge and casino executive Clifford A. Jones was lieutenant governor.

To convince their colleagues of the importance of the legislation, the southerners flew the entire Legislature to Las Vegas for a tour.

“For many of the Northern Nevada legislators,” said Jones, “it was their first trip into the southern part of the state.”

The legislation passed, and Vegas Valley voters approved formation of the district by a vote of 4,171 to 538.

In 1947, wearing his Elk’s Club antlers, Exalted Ruler C.D. Baker announced that the club would build “one of the finest all-purpose stadiums of any smaller community in the Southwest.” The Elks produced the city’s annual Helldorado Days, and members had planned since before the war to construct a facility, but material shortages had caused it to be postponed.

The club bought a piece of railroad land near the old Las Vegas Ranch, and an impressive group of Elks set itself to work. The exalted ruler was an engineer, and the construction committee included James Cashman, who sold heavy equipment, and J.M. Murphy, a state road engineer.

There was no need to erect a costly grandstand structure. Baker ingeniously carved an amphitheater out of a bluff on the property. Elks Stadium and Cashman Field, as the complex was named, had baseball and football fields, rodeo grounds and space, plenty of it.

It is hard to overemphasize the importance of Cashman Field to the civic life of Las Vegas. For its time, the stadium was enormous, capable of accommodating 20,000 people. In the 1950s and 1960s, Helldorado was the year’s most important event for locals and a strong tourist draw. Cashman Field also was home of the Las Vegas Wranglers minor league baseball team.

Baker assured the survival of the community of Henderson in 1949, when he pushed through a bill allowing Henderson residents to purchase the company houses where they lived. Most had been war workers at Basic Magnesium, and their homes were rented from the company. Baker’s bill also allowed industrial buildings at the BMI complex to be leased or sold to private industries. It transformed Henderson from a temporary company town to a community in its own right.

In June 1950 Baker announced that he wouldn’t seek a third term in the Senate. He had done all he could for Southern Nevada at the state level, and it was time to head home. (Coincidentally, that same year, he went to Washington, D.C., to attend the command school and general staff college and was promoted from lieutenant colonel to full colonel in the reserves.)

Baker and local attorney George Franklin Jr. both challenged incumbent Ernie Cragin in the 1951 mayoral race. Baker made a campaign issue of the city’s poor water, power and phone service, and chided Cragin for failing to call those shortcomings to the attention of the Nevada Public Service Commission.

Baker prevailed.

UNLV History Professor Eugene Moehring, in his book, “Resort City in the Sunbelt: Las Vegas 1930-1970,” wrote: “The trend in Las Vegas politics after 1945 was clear: Like their counterparts across the sunbelt, local voters wanted a well-managed, business-oriented government with low taxes and a commitment to growth.” Upon election, Baker promised a progressive administration, and it was so. His top priority, he said, would be to establish assessment districts to pay for much-needed improvements in the city’s water, sewer, electrical and phone system.

The streets in the mostly black West Las Vegas were still unpaved when Baker took office, and he astonished many when he kept his campaign promise and spent $10,000 to pave B, C and E streets. By 1955, property values in the area had risen enough to justify paving the remaining streets.

But while Baker was not an open segregationist, as Cragin had been, he did little else specifically for the black community.

In a token gesture shortly after Baker was elected in 1951, he posed for a newspaper picture crowning Doretha McKinney “Miss Bronze Las Vegas.”

That fall, he tackled the issue of juvenile delinquency head-on. The problem consisted mostly of drunken adolescents driving fast and generally raising hell.

Baker met with school officials, tavern owners and student representatives, and he posed two questions: First, do you want the city government to vigorously enforce underage drinking laws? And second, are you willing to back us up?

“We can’t do it alone,” gruffed Baker. “If the people of this community want the situation straightened out, we certainly can get the job done, but it’s everybody’s responsibility.”

Then, as now, many parents refused to believe their own kids were part of the problem, and Baker complained that parents applied pressure when cops tried to crack down.

Following up locally on legislation he had pushed as a state senator, Baker headed the drive for an $8.7 million bond issue, which passed by 82 percent in the fall of 1953. The money was used to buy the railroad’s water system and improve it and to construct pumping stations and pipelines to carry Lake Mead water into the valley.

That same year, 1953, according to Moehring, Baker “inspired the public with a bold agenda.” In addition to supporting the proposed convention center, he called for more than $1 million in new bond issues to pay for a city fire alarm box system, for a railroad underpass at Owens Avenue and for expansion of the city’s overtaxed sewage treatment plant.

Voters did not feel overtaxed, though, and approved the bond issues, and returned Baker to the mayor’s chair.

“Within four years of taking office,” Florence Lee Jones wrote, “Baker and the board that served with him had doubled the miles of paving and sewer lines in the city, tripled the number of street lights and miles of sidewalk and more than doubled park acreage in the city.”

But since progress often resembles chaos, Baker’s projects were a mixed blessing. Locals often found streets dug up and suffered the occasional water, power or phone outage.

Baker responded to complainers in late 1954, calling them “snipers,” and stating simply “these things have to be done.”

Despite his no-nonsense demeanor, Baker was increasingly tourism-conscious and willing to step out of character in the interests of boosterism. In 1953, his honor was a guest, along with Tennessee Ernie Ford, on the Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy Show on NBC Radio. Ford and McCarthy, the latter a dummy manipulated by ventriloquist Bergen, enacted a melodrama in which they were Pony Express riders, carrying an important and mysterious package to Las Vegas. As they delivered the package to Baker, he revealed that it contained “cherries for our slot machines.”

Less amusing was the time Baker almost fell into the ocean from a great height. He was aboard a TWA Constellation in 1956, en route back to Las Vegas from a political conference in San Francisco. As the plane circled the Bay, an emergency door flew open and slammed into the seat occupied by Baker. The mayor and his aide, Robert Notti, struggled to get the door closed, and eventually succeeded, when the captain left the cockpit to lend a hand. Notti and Baker then exchanged seats.

Baker’s final break with his former ally, Sen. Pat McCarran, came in 1952. The senator had been repeatedly blasted by Las Vegas Sun publisher Herman “Hank” Greenspun for supporting his Commie-baiting colleague, Joseph McCarthy. In retaliation, McCarran contacted owners of certain Strip casinos and urged them to pull advertising from the newspaper. The boycott quickly spread to downtown. When he learned of McCarran’s move, Greenspun filed a $225,000 lawsuit against McCarran and some 40 hotel executives, claiming a criminal conspiracy. According to Greenspun’s autobiography, Baker called together the downtown casino bosses, and he didn’t mince words.

“No man from Washington, or ex-con man out on the Strip is going to run this city, or ruin a legitimate business. It should be straightened out immediately; but if they want war, they shall have it.”

The boycott ended, and Greenspun won an $80,500 settlement.

McCarran faced re-election in 1956, and in 1954, Baker announced that he would run for the Senate seat McCarran held. But McCarran died that same year, and so did Baker’s plan. Level-headed Alan Bible was appointed to fill McCarran’s unexpired term, and Baker backed him for re-election.

Baker retired from the mayor’s office in 1959 and devoted himself to his business interests, the state party organization and to freelance boosterism.

In late March 1963, he appeared in the Legislature as president of the Nevada State Association of Realtors to speak in favor of a bill, “allowing apartment house tenants to own their individual rooms.” Baker explained that the new class of housing was fairly common in the East, where tenant-owned apartments were called “condominiums.” The bill passed.

In March 1966, Baker publicly announced his retirement from politics, business and everything else.

“I’ll be turning 65 soon,” Baker growled. “I guess I’ll have to apply for my Social Security.” He would live until 1972.

But his old bluntness surfaced when, after retirement, he was asked by a reporter to predict the future of Southern Nevada.

He replied that he was confident that better elements of Southern Nevada society would ultimately head off “interlopers and the infiltration of hoodlums.”

He was less optimistic about the future of Nevada politics.

“I deplore the lack of interest of people in preventing low-caliber persons from getting into public places.”

Thus spoke The Colonel.

Dismissed.

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full