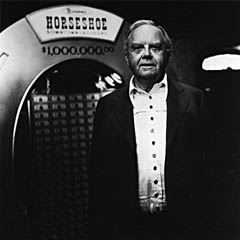

Benny Binion

Men and cities can be judged by their heroes, and it tells you something of Las Vegas that there are only two historic equestrian statues in the city. There’s Rafael Rivera, said to be the first white man to find the Las Vegas Valley, and there’s Benny Binion, said to be the first to give gamblers a fair shot at winning big.

The Binion statue suggests Las Vegans value the Western traditions of individuality, fairness and a good gamble.

In some 40 years operating Las Vegas casinos, Binion injected courage into an industry too timid to take a high bet. He forced gambling houses to change from sawdust joints to classy, carpeted casinos. He and his sons changed poker from a kitchen-table pastime into an important casino game. He was one of the boosters who made Las Vegas the home of the National Finals Rodeo.

Binion did not merely create tourist attractions, but was so famously colorful that he personally became one.

Born in 1904 in Grayson County, Texas, about 60 miles north of Dallas, Binion was seriously ill often as a child. His parents decided to let him accompany his father on journeys as a horse trader, hoping the outdoor life would restore his health. It did, but Benny never got around to attending school.

He became skilled at horse trading and skilled at gambling in the campgrounds where traders gathered awaiting market days. “Everybody had his little way of doing something to the cards,” he told an oral historian from the University of Nevada in the 1970s. “I wasn’t too long on wisin’ up to that. Some of ’em had different ways of markin’ ’em, crimpin’ ’em … There was fellows … that had what they call ‘daub’ they put on dice. And you could roll the dice on a layout, and this daub caused the dice to hesitate, slow down, and turn up on their number. … I never did learn how to do any of these tricks like cheat people, which I’m kind of proud of now. But I was always pretty capable about keeping from gettin’ cheated.”

First the boy ran errands for gamblers. Then the young man steered customers to clandestine gambling joints. Meanwhile, he made money in the bootlegging business. About 1928 he opened an illegal “policy” game, or lottery.

In 1936 Dallas unofficially adopted a policy of tolerance toward minor vices, the better to host the Texas Centennial celebration. Police wouldn’t put gamblers out of business, but would raid and fine them from time to time. Binion had crap tables built specially in crates labeled as containing hotel beds. “If we had half an hour’s notice we were going to be raided, we could clear it out,” Binion told a reporter in the ’70s.

Even in the Depression, Dallas was flush with oil money. During World War II, entire divisions of GIs learned to shoot craps in barracks and motor pools, and many headed for Dallas to buck the bigger banks and honest dice Binion was known to provide.

This river of money also attracted pirates. In those days Binion carried three pistols — two .45 automatics and a small .38 revolver. In 1931, Binion suspected fellow bootlegger Frank Bolding had stolen some liquor and argued with him in a back yard. “This guy was a real bad man, had a reputation for killing people by stabbing them,” related Binion’s son, the late Lonnie “Ted” Binion, after Benny’s death. “He stood up real quick and Dad felt like he was going to stab him, and rolled back off the log, pulled his gun, and shot upward from the ground. Hit him through the neck and killed him.”

This athletic marksmanship was the genesis of Binion’s nickname “The Cowboy,” but also earned him a murder conviction. Bolding did have a knife on him, but hadn’t pulled it. Yet Binion only got a two-year suspended sentence, said Ted, because the deceased’s reputation was so bad.

Five years later, Binion shot and killed a rival numbers operator, Ben Frieden. Wounded, Binion was cleared on grounds of self-defense.

No other killings were ever officially attributed to Binion, though a number of his rivals — and a number of his allies — died in a gang war that broke out in 1938.

Herbert Noble was called “The Cat,” for he was thought to have nine lives. In 1946 he was shot in the back; in 1948 his car was riddled with bullets; in 1949 he found dynamite wired to the starter of his car and later got shot in another high-speed chase. But when somebody blew up his car, killing his wife instead of him, he blamed Binion and spent the rest of his life trying to even the score.

Noble was a pilot, and in 1951 a police officer caught Noble rigging an airplane with two large bombs, one high explosive and one incendiary. He had a map with Benny Binion’s Las Vegas home — the structure that still stands on Bonanza Road — clearly marked.

Noble escaped or survived 11 known attempts to kill him — involving bombs, automatic rifle and machine-gun fire — before a bomb planted in front of his mailbox got him in 1951.

Binion denied responsibility for the eventfulness of Noble’s final years, and particularly for the death of Noble’s wife. By then a reform administration had encouraged Binion to leave Dallas, and he settled in Las Vegas. “When I realized how good it could be up here, I said, ‘Let ’em have Texas.’ ”

Binion opened a club on Fremont Street in partnership with J.K. Houssels, but soon split with him, though they remained lifelong friends. The split was over Binion’s desire to increase the limit on the size of bets the house would accept. When he opened his own place in 1951, naming it Binion’s Horseshoe, he set the craps limit at $500 — 10 times the maximum at other casinos.

Most gamblers use some sort of system. Commonly, if a gambler wins a $10 bet, he will then bet the original $10, plus the $10 won. All gamblers dream of riding a streak of luck and a system into real money … but casino owners have nightmares about the same event.

The house limit made it harder to do. A person betting $10 and doubling it each time he won would be blocked on the fourth bet by the $50 limit. Under Binion’s $500 limit, he could keep doubling until the seventh bet. If the doubler won all seven bets he could win $1,130 at Binion’s compared to $270 anywhere else.

The new limits made Binion’s famous immediately, and other casinos were forced to raise their own limits accordingly.

Some in the industry didn’t go along willingly. “He was going to raise the keno limit to $500. Dave Berman said if he raised it, he’d kill him,” related Ted Binion, a few years before the younger Binion’s death in 1998. It was one of the few times on record that Benny backed down. He had no doubt Berman would try to make good his threat, and Binion did not want another gang war. The difference was worked out in some fashion unknown to him, said Ted, and the limit was raised a few months later without incident.

Over 40 years the Binions pushed the limits ever upward to $10,000. Gamblers who felt like going higher could do so, as long as they did it on the first bet. Back in 1980, a player named William Lee Bergstrom asked if he could really bet $1 million. He didn’t have the money at the time, but the Binions told him he could.

A few months later he showed up with $777,000, apologizing that he couldn’t raise a whole million. They never bothered to convert the money to chips, but laid the whole suitcase of cash on the “don’t pass” line, and the woman holding the dice sevened out in three rolls. Binions’ counted out another $770,000 to Bergstrom, and Ted Binion escorted him to his car.

Bergstrom came back over the next few years. He bet $590,000 and won. Bet $190,000 and won. Bet $90,000 and won.

Then, in November 1984, he brought in a whole million. He deposited it in the casino cage, and Ted told him he could bet it on any game. Ted recalled, “He run a few feet ahead, up to a crap table, put his finger on the table and said ‘$1 million on the don’t pass.’

“It was the comeout roll so the shooter wanted a seven, and they come ace-six. It was all over in one roll.

“I felt like electricity run through me. And Bergstrom pulled his finger off that table like it was on fire!”

Three months later Bergstrom committed suicide. “But you know, he was still $400,000 winner,” pointed out Ted. He knew Bergstrom by then, and believed he died not for money, but for love.

Jack Binion, who became president of the casino, remembered that his father was first to put a carpet in a downtown casino, first to have limousines to pick up customers at the airport and first to offer free drinks to slot machine players.

“Everybody was comping big players, but Benny comped little players,” noted Leo Lewis, who was comptroller at Binion’s and later ran Strip resorts. “He said, ‘If you wanta get rich, make little people feel like big people.’ ”

In the 1950s Benny served a hitch in prison for tax evasion, stemming not from the casino profits but from his Texas operations. He had to sell majority interest in the casino to finance his legal fights. The family regained control in 1964, with Jack becoming president, Ted casino manager, and their mother Teddy Jane, managing the casino cage almost until her death in 1994. Three Binion daughters, Barbara, Brenda and Becky owned percentages but were not active in operations until 1998, when Jack, after a bitter legal fight among the siblings, surrendered the presidency to Becky and sold her his interest. Jack Binion became active in gambling in other states.

Benny himself never held a gambling license after going to prison, but until his death in 1989 was on the payroll as a “consultant.” In the 1970s he bragged that the Binion brothers, then in their 30s and veteran casino executives, “mind me like a couple of 6-year-olds.”

Insiders, however, understood that the boys had good ideas of their own, which Benny was smart enough to rubberstamp. The most famous was the World Series of Poker. Tom Morehead of the Riverside Casino in Reno actually started it, but got out of the gambling business and allowed Jack and Ted to take over the tournament in 1970, when it was still in its infancy.

At that time, the Binions didn’t even offer poker in their famous but small casino; floor space was too precious to waste on a game in which players vied for each others money, and the casino could collect fees for keeping the game but had no chance to win big. (Much later, when they acquired an adjacent high-rise hotel, the Binions added a poker room.)

Many other casinos also did not offer it because the game was not entirely respectable. The game is hard to police, and was associated with cheating long after other Nevada casino games were universally honest. A few casinos offered it as a customer service, but intentionally kept it inconspicuous.

The Binions, by contrast, promoted poker. Their original world series games were winner-take-all challenges (today the prize money is split among several finalists) and were not invitationals but open to anybody with $10,000 to buy-in. The open aspect was the secret of success; it lured rich suckers and unknown poker prodigies, but it also lured legendary pros such as Amarillo Slim Preston and Johnny Moss, who hoped to pluck the newcomers. They usually did, but sometimes the new guys won and themselves became legends, and that hope kept them coming back year after year.

The Binions devised special rules to force the game to a resolution before everyone got bored with it, making it an event which could be, and was, nationally televised. Within a few years tournament poker was played everywhere poker was legal. And the positive national attention brushed off the lingering grains of disrepute, so that nearly every casino added the game to the attractions.

One of Binion’s final gifts to Las Vegas was the hand he played in attracting the National Finals Rodeo to Las Vegas every December.

While the second generation of Binions evolved into modern businessmen and business- women, Benny remained a Texas tough guy with eclectic tastes. Benny wore gold coins for buttons on his cowboy shirts, but was never seen in neckties. He didn’t shave every day. Despite felony convictions which normally prohibit ownership of firearms, he carried at least one pistol all his life and kept a sawed-off shotgun handy.

In the 1970s, if the police needed lots of money on short notice to execute a drug sting operation, they could get it from Binion’s casino cage. Yet he didn’t ask the police for such ordinary services as arresting a slot cheater or pickpocket caught on the premises. Those were handled by burly, surly security guards, and the perpetrators rarely sinned again until their casts were removed.

Binion ran what was thought to be the most profitable casino in Las Vegas (privately held, it never had to report earnings publicly) but he didn’t keep an office; he did business from a booth in the downstairs restaurant. Nobody needed an appointment to talk to him; they asked him personally for his ear, and usually got it. When he invited one to sit down and have a bowl of the Horseshoe’s famous chili, the guest was often a senator or federal judge. And just as often, it was some old Texan from a one-windmill spread, trading stories of rodeos and crap games.

“He was a guy you could shake hands with, and feel you had met a real American character,” said Howard Schwartz, who has documented the development of Las Vegas as an editor at Gambler’s Book Club. “That was what made the place. It wasn’t the classiest joint in town, but it was an authentic and unique experience. When you met Benny Binion, you felt you’d been part of history.”

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full