Authority sets sights on Lincoln watersheds

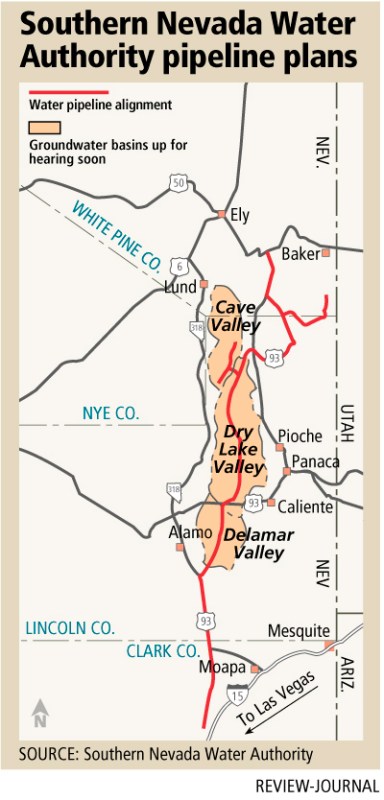

With water now in hand at the north end of its proposed pipeline from White Pine County to Las Vegas, the Southern Nevada Water Authority is turning its attention to the basins in between.

The authority has sent a letter to State Engineer Tracy Taylor asking him to convene a hearing on its next round of groundwater applications in rural Nevada.

“This is very important to us,” said Kay Brothers, deputy general manager for the water authority. “With the drought on the Colorado River, every acre-foot (of water) is important to us.”

The authority’s specific request calls for a four-day hearing, starting Jan. 14, to consider its plans to pump more than 11.3 billion gallons of groundwater a year from three watersheds in central Lincoln County.

Cave Valley, Dry Lake Valley and Delamar Valley lie in a north-south line bracketed by U.S. Highway 93 and state Route 318. The northern one-third of Cave Valley is in White Pine County.

“We have two applications (for water rights) in each basin. We’re asking for action on those six applications,” Brothers said.

The authority wants to pump about 3.8 billion gallons annually from each valley and pipe it to Las Vegas, where stretched through reuse the combined amount could supply almost 120,000 homes.

The authority requested the hearing in a June 29 letter to Taylor, who administers water rights statewide as head of the Nevada Division of Water Resources.

Taylor was on vacation and has yet to see the letter, said Susan Joseph-Taylor, chief of the division’s hearings section.

It will be up to Taylor to decide if and when a hearing should be held, but Joseph-Taylor said a pre-hearing conference could probably be held within the next couple of months to bring all of the interested parties together.

Taylor and Joseph-Taylor are not related.

In April, the state engineer granted the authority the right to pump at least 13 billion gallons of groundwater a year from Spring Valley, a 1 million-acre watershed in White Pine County about 250 miles north of Las Vegas.

The Spring Valley decision came after a contentious, two-week hearing last year that drew pipeline opponents from White Pine County, neighboring Utah and elsewhere.

Slightly less rancor is expected when a hearing is held on the three Lincoln County basins.

In 2003, the authority entered into a sweeping agreement with Lincoln County that spells out which groundwater basins each entity would be allowed to develop in the rural county about 60 miles north of Las Vegas. The agreement also clears the way for the county to share in the use — and the price — of the pipeline network the authority plans to build at a cost of at least $2 billion.

In return, Lincoln County agreed to drop the protests it filed with the state more than 15 years ago, when the Las Vegas Valley Water District launched a sweeping grab for unappropriated groundwater across the southern half of the state.

That massive filing in 1989 and 1990 involved more than 100 applications in four counties, including the water rights the authority just requested a hearing on in Cave, Delamar and Dry Lake valleys.

Pipeline opponents are already promising to pack that hearing.

Bob Fulkerson, state director for the Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada, said the absence of any official protest from Lincoln County shouldn’t make that much of a difference.

“This will still be a contentious hearing,” Fulkerson said. “They (Lincoln County officials) can make all the agreements they want, but that doesn’t negate the damage that this project is going to do to the land out there.”

Water authority officials insist so-called “in-state resources” can be developed without harming the environment or jeopardizing the livelihoods of rural Nevada residents.

The authority hopes to begin delivering rural groundwater to Las Vegas by 2015 to supply growth and insulate the community from drought on the Colorado River.

About 90 percent of the Las Vegas Valley’s drinking water now comes from the Colorado by way of Lake Mead.