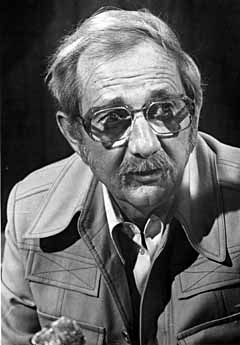

Al Bramlet

In February 1977 Al Bramlet, the most powerful labor leader in Nevada, arrived at McCarran Airport after a business trip to Reno. He telephoned his daughter from the airport, telling her he had just arrived and would be home shortly.

Shortly afterward, Sid Wyman, an executive at the Dunes Hotel, received a telephone call from Bramlet, asking him to send $10,000 to Benny Binion, operator of the Horseshoe. The cash would be used for a personal matter, Bramlet said.

His car was still parked at the airport when police began looking for the boss of Culinary Workers Local 226.

Three weeks later a couple hiking in the desert west of Mount Potosi found his body.

Bramlet was a manifestation of a Nevada fact of life: Labor unions and those who control them can be remarkably important in an economy dominated by a single industry.

Restaurant and hotel workers were first organized in the 1890s but the union did not become powerful until President Franklin Roosevelt sponsored laws that increased the bargaining power of relatively unskilled workers, allowing them to join forces with craftspeople like chefs. The National Labor Relations Act, also called the Wagner Act, guaranteed the right to strike.

Born on an Arkansas farm about 1917, Bramlet went to work as a dishwasher in Joliet, Ill., at the age of 14. After a hitch in the Navy during World War II, he was discharged in Los Angeles, found work as a bartender, and later became a business agent for a bartenders local union. In 1946 Bramlet was sent to Las Vegas to help Culinary Workers Local 226. In 1954 he became the local’s secretary-treasurer.

By 1963, Bramlet had brought more than 8,000 workers into the local. Review-Journal columnist Jude Wanniski estimated the city was “98 percent organized” despite a state right-to-work law, and noted that Bramlet had been able to negotiate a steady increase in wage scale and benefits.

Irwin Molasky, a co-founder of Sunrise Hospital, remembers that by the early 1960s Bramlet had a deal with Sunrise to provide medical care to all Culinary employees.

In Las Vegas, working couples from the culinary trades entered the middle class, owning homes and sending children to college.

But union members were beginning to kick because Bramlet hogged the power. Political consultant Don Williams, who still holds an inactive Culinary union membership, said, “People just weren’t being treated fairly. Only a few people ran it, and there weren’t a thousand captain’s jobs, only so many good cocktail jobs where they could make great tips, and only certain people could get those jobs.”

But efforts to replace Bramlet failed.

Bramlet was proud of getting contracts without many work stoppages.

But in 1967, 12 downtown hotels were closed for six days before reaching a contract. In 1970 Local 226 and Bartenders Local 165 struck the International (now the Las Vegas Hilton), the Desert Inn and Caesars Palace. Management then locked out the unions at 13 other hotels.

“It was a showdown situation,” Bramlet said later. “It had come to the point that management would no longer bargain because they didn’t think we would go out.” The four-day strike bought wage and benefit increases amounting to 31.5 percent over three years for 13,000 to 14,000 workers.

In 1976 the Culinary joined Musicians Local 369 and Stagehands Local 720 in striking 15 resorts for 15 days. The key issue was a management demand for a no-strike, no-lockout clause. It was replaced with a clause that required members to ignore picket lines of other unions in certain situations, such as jurisdictional disputes and organizational drives. Management had feared Bramlet would use his Culinary union to organize resort dealers.

Newspapers editorialized that labor, and particularly the Culinary union, ran state government.

Ralph Denton, who was active in the Democratic Party and ran for the congressional nomination in 1966, said Bramlet was not a political kingmaker because “Bramlet turned off as many people as he impressed. He was embarrassing for me when I ran for governor. He essentially put out orders that people had to vote how he told them. Well, of course people resented that and I even resented him telling them that, because I knew it would hurt me more than it helped.”

But Bramlet was part of the power elite of Las Vegas. “He knew them all; he was part of that group,” said Molasky. “He was a guy who loved a joke, mixed well. I’d see him at charity events.”

In 1973, when City of Hope chose Bramlet to be honored at its annual banquet, the sponsoring committee consisted almost entirely of hotel executives. That same year, Bramlet’s union and the hotels reached a contract agreement without a strike.

Bramlet owned or had interests in private businesses that served the same industry which employed his members. A cleaning company got contracts to clean casinos, and an interior furnishings company sold shelves and furniture to shops in Strip resorts. Such cozy arrangements weren’t illegal if disclosed to the National Labor Relations Board. And they resembled the practices of many Southern Nevada public officials of his time.

An editorial in the Valley Times said Bramlet had become a millionaire this way. But after his death, his estate was officially estimated at $300,000, with heavy claims by creditors against that amount.

When he died Bramlet was being sued by a group of bell captains who claimed he had negotiated away their traditional rights of arranging certain services for hotel guests, such as show reservations, and set up a company which provided the same services.

Bramlet could play rough. Hershel Leverton, owner of the Alpine Village Restaurant, claimed Bramlet showed up at his bar about 15 minutes before opening time one day in 1958. “Bramlet came in out of the blue and said we had 15 minutes to join or he’d put me out of business.”

” `Take your best shot,’ I told him, ‘and 15 minutes later 20 pickets started marching.”

The pickets would be there for the rest of Bramlet’s life, nearly 20 years.

In December 1975 two bombs were planted on the restaurant roof and went off about 30 seconds apart, about 9 p.m. on a busy Saturday night, endangering more than 400 patrons, employees and passersby. In the mid-1980s, the President’s Commission on Organized Crime found that infiltration of Chicago-area locals had begun in the era of, and by the organization of, Al Capone. His heirs continued to wield power in those locals, and the commission received testimony that Tony Accardo personally picked Ed Hanley as the international union’s president.

Bramlet was cherished by the parent union for his successes; contracts he negotiated were used as models throughout the country. But he was also resented for his independence. One of Hanley’s major goals was centralizing local health and welfare funds, under the control of the international. Such mergers were legal but had often led to abuses in various unions. Bramlet was determined to keep the funds in Las Vegas.

The bombings and Bramlet’s death occurred during years when the Chicago mob was trying to claim a larger share of Las Vegas. After his death, one of the men convicted of murdering him testified that in 1976, a thug known to work for mob enforcer Tony Spilotro, told Bramlet he would be killed if necessary. To make the point, “They knocked his ass off the barstool and stomped him,” said Gramby Hanley.

Gramby Hanley and his father, Thomas Hanley, were unrelated to Ed Hanley.

The Las Vegas Hanleys were also contract bomb planters and arsonists, and according to Gramby, Bramlet became their best customer. On the morning of Jan. 12, 1976, a bomb blew up David’s Place, a nonunion gourmet restaurant on West Charleston Boulevard near Rancho Drive. A year later, sophisticated booby-trap bombs were discovered on the same night in autos outside the Village Pub on Koval Lane and at the Starboard Tack restaurant on Atlantic Avenue. Each failed to ignite. These restaurants were also involved in labor disputes with the union.

But according to later testimony, Bramlet balked at paying for bombs that didn’t go off.

The Hanleys stewed over the perceived injustice for a couple of months. They did not stew in silence. On Feb. 22, 1977, Bramlet told his wife police had warned him Tom Hanley was out to get him. The next night, she testified, he got a phone call from one of the Hanleys and agreed to meet him two days later at the union hall and pay him.

But on Feb. 24 the Hanleys and Eugene Vaughan waited for Bramlet in the parking lot of McCarran Airport. Bramlet had a permit to carry a .357-caliber revolver, but federal laws and the airport metal detectors meant he would be unarmed upon arrival after a business trip to Reno. As Bramlet walked toward his car, Vaughan later testified, Gramby pointed a pistol at him and ordered, “Get in the van or I’ll kill you right here.” Bramlet was handcuffed and gagged with duct tape.

They rode into the desert. On the way, Tom assured Bramlet he wouldn’t be murdered. “You’ve got to come up with some money or we’re all going to prison.” So the group drove to a pay telephone and Bramlet called Wyman, asking for the loan of $10,000.

Then they drove back into the desert. Tom Hanley said, “Hey, Al.”

Bramlet turned and Tom Hanley shot him, Vaughan said. He was shot six times in all, including once in each ear.

Gramby Hanley said years later that he had not expected Bramlet would be killed after cooperating. “Mr. Bramlet had as much right to live as anyone else. But I wasn’t about to get shot over him, with my dad and Vaughan both drunk and armed.”

The men stripped the body of clothes and buried it under a pile of rocks. Vaughan told the story to a woman, and eventually police learned it. Gramby and Tom Hanley pleaded guilty and got life sentences without parole, while Vaughan got less in return for his cooperation.

Gramby Hanley disappeared into the Federal Witness Protection Program, emerging briefly in 1982 to testify before a U.S. Senate panel investigating illegal union activities. He said that Bramlet had been selling his Nevada assets and preparing to flee the country, fearing he might be caught in the bombings and other matters, when the Hanleys killed him.

In 1995 the international union signed a consent decree allowing a court-appointed monitor, the former chief of the Justice Department’s organized crime and racketeering unit, to oversee union activities. Four key International officers resigned about the same time. In 1998 Ed Hanley stepped down.