Summerlin glider pilot who survived D-Day shares story of crash the night before

With Veterans Day just around the corner, Americans take time to thank those who have put their lives on the line.

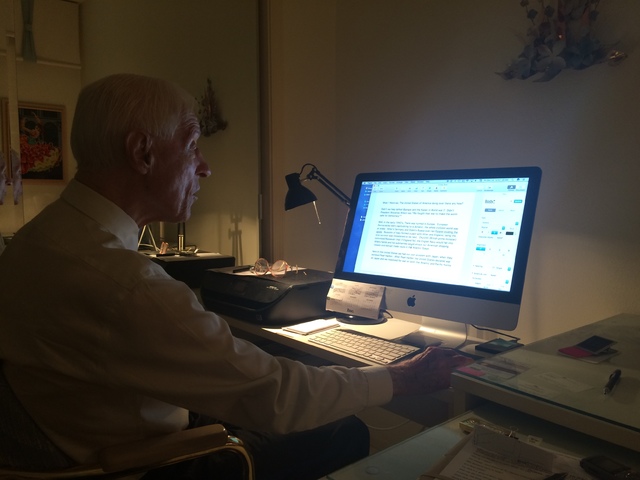

Frank Kology, 95, is one of those people.

He was 21 and a newlywed when he joined the effort in World War II.

“I was young. It was an adventure,” he said.

Kology was assigned to be a glider pilot with the U. S. Army Air Corps and sent to England. Glider pilots delivered troops and supplies before helicopters were a regular part of military action.

On June 5, 1944, one day before more than 160,000 allied troops stormed the beaches of Normandy, Kology and roughly 200 other pilots in his operation got in their gliders. They were to be taken across the English Channel, each one towed there by military transport aircraft, the Douglas C-47 Skytrain. On board with him were two infantrymen and a fully-equipped Jeep anchored to the floor of his 40-foot-long craft. The Jeep was likely needed to pull an anti-tank gun.

Then, things went wrong.

Kology had no radio communication with the C-47 pilot. Not hearing any responses to his questions, he asked the pilot to blink his lights — one for “yes” and two for “no.” The C-47 pilot blinked “yes.”

Then, the weather — it was supposed to be a moonlit night, but they encountered clouds.

Five miles inland and over enemy territory, Kology’s glider was set free. He was on his own.

His glider, a snub-nosed craft whose nose hinged up to allow cargo to be loaded, was heavy, bulky and not in the least aerodynamic. He was at the whim of gravity.

Enemy tracer bullets began zinging past him. If any of them pierced the C-47, it would blow up. If any hit the jeep’s gas tank, he would blow up.

“That’s when I grew up,” he said. “I’m going, ‘That’s the enemy down there. This is for real.’ ”

He dropped down into the inky night, five miles inland and 500 feet above land that he couldn’t see. There was only the horizon line to indicate how low he was.

There were no lights. The landing sites were farmers’ fields and meadows with trees and hedges. He’d studied aerial photos while stationed in England and determined the trees were 30 feet tall.

Wrong. They were actually 60 feet tall. As he came in for his landing, Kology’s angle was too low. He hit the trees, tearing off the right wing. The glider plunged to the ground, hitting soft dirt. Miraculously, no one was hurt.

“Scrapes and bruises, that’s all,” he said. “I was young, hail and hearty.”

Time was of the essence. He was in enemy-held territory. Moments after getting out of the wreckage, he grouped with others who’d landed, assessed their situation and went to check their maps.

Suddenly, there was the sound of boots. They were coming closer. He clutched his sidearm, a .45-caliber pistol. There was a pre-arranged code.

“Thunder,” the Americans yelled out.

“Lightning,” came the response.

It was a group of soldiers who’d been separated from their unit. His group headed to the command post where the glider-carried supplies were to help those who would storm the beaches the next day. Kology was now an infantryman, along with about 20,000 other men who were there. They dug fox holes, protection from lobbed shells.

On D-Day, June 6, he and his rifle provided support coverage, close enough to see the faces of the men storming the beach.

After the war ended, Kology returned home and earned three degrees. He become a school principal and, later, a stockbroker.

Kology and his wife, Dolores, had no children, but they enjoyed 72 years together before her death in 2015. View readers may recall them as the couple whose daily walks added up to where they could have walked to the North Pole.

Lillian Jennings is a neighbor of Kology’s and said that when she learned of his scary landing, she thought, “Gosh, what this guy has been through … his adventures as a glider pilot and the nature of his descent when his glider was almost inoperable, he had very little control.”

Kology now gives talks about his adventures in Wolrd War II. He was one of the lucky ones.

Gliders spearheaded nearly every major allied assault during the war. By the end of it, more than one-third of all allied glider troops had been killed or wounded, according to the book, “D-Day: 24 Hours that Saved the World.”

To reach Summerlin Area View reporter Jan Hogan, email jhogan@viewnews.com or call 702-387-2949.