Solar plants fire back on burning bird issue

For the second time in a year, a new solar power plant is facing unwanted attention for scorching birds in midair with concentrated sunlight.

During a January test at the Crescent Dunes Solar Energy Project near Tonopah, about 225 miles northwest of Las Vegas, biologists counted roughly 115 birds that were burned when they flew through the beam of concentrated sunlight from the project’s mirrors. Beam temperatures can exceed 900 degrees.

There is a gruesome nickname for birds injured or killed this way: Biologists call them “streamers” for the telltale puff of smoke and flame they give off as their feathers ignite and they fall to the ground.

But the developers of Crescent Dunes insist they have found a way to generate power without hurting birds by the dozens. And they think the issue of bird deaths at solar plants is largely overblown.

Kevin Smith is the CEO for SolarReserve, the project’s Santa Monica, Calif.-based owner and operator. He said Crescent Dunes has seen “zero bird fatalities” in the past 35 days of commissioning work, thanks to operational changes the company made in the wake of the Jan. 14 test.

“We don’t expect the number will be zero on a long-term basis, but we do expect the number to be relatively low,” Smith said. “One of the fundamental goals for SolarReserve is minimizing the environmental impacts of its projects at every stage — from site selection and construction to full operational use.”

Company spokeswoman Mary Grikas said the bird deaths occurred during early testing when the plant was in “standby” mode, mirrors focused on a single point in the sky above the central heating tower and creating a bright spot in the air.

During normal operations, the plant might spend a few minutes in standby mode, but on Jan. 14, it remained that way for several hours, she said.

Project engineers since have developed a way to direct the mirrors in standby mode to spread the beam over hundreds of yards rather than training it on a single spot, resulting in a field of light safe for birds to travel through.

“Once the mirrors are focused on the tower, the brightness and solid structure is enough to deter birds,” Grikas said.

The modified procedures will have no impact on power production at Crescent Dunes, she said.

“We expect to be generating electricity in the next 30 days, with full commercial operation scheduled for the end of May,” she said.

The 110-megawatt plant will sell its power, enough for about 75,000 homes, to NV Energy under a long-term contract.

A PLEA FOR ‘PERSPECTIVE’

Smith finds media reports about “streamers” at solar plants and bird strikes at wind farms a little bewildering.

Such deaths are unfortunate and should be prevented to the extent possible, he said, but the number of birds killed each year by renewable energy projects doesn’t amount to much compared with the carnage caused by fossil fuel power plants and other human-made hazards.

“You’ve got to look at this stuff in perspective,” Smith said.

By some estimates, hundreds of millions of birds die annually in collisions with buildings, power lines and vehicles.

But when 133 birds were scorched in six months last year at another, even larger concentrating solar array — this one developed by NRG Energy, BrightSource Energy and Google on the California side of the Ivanpah Valley, about 40 miles south of Las Vegas — the deaths made international news.

A U.S. Fish & Wildlife report on the situation didn’t help matters by labeling such sites potential “mega-traps” for birds, bats and bugs.

“The strong light emitted by these facilities attracts insects, which in turn attract insect-eating birds, which are incapacitated by solar-flux injury, thus attracting predators and creating an entire food chain vulnerable to injury or death,” the report said.

The analysis also warned of birds dying in collisions with the mirrors, which they mistake for bodies of water, particularly when the panels are turned upward, reflecting blue sky.

At 377 megawatts, the Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System is the world’s largest concentrating solar power plant. It features 3,500 acres of mirrors that track the sun through the sky and focus its energy onto three boiler towers, each rising almost 500 feet from the desert floor.

The $2.3 billion project backed by $1.6 billion in federal loan guarantees went online in February 2014. Project officials could not be reached for comment.

SOLAR INDUSTRY STILL RISING

The “streamer” problem is not shared by all solar plants. Static photovoltaic arrays, like those springing up in Eldorado Valley south of Boulder City and on the Nevada side of the Ivanpah Valley, absorb the sun’s energy and convert it directly to electricity. The biggest risks they pose to birds are from collision with the panels or the rare electrocution.

Concentrating solar-thermal arrays such as Crescent Dunes and Ivanpah Solar use focused energy from the sun to create steam that drives turbines.

One benefit of such systems is a smoother, less variable power stream. Photovoltaic panels can see sharp drops in output the moment a cloud passes in front of the sun, but it takes longer for solar-heated liquid in a boiler to cool and stop generating steam.

What sets Crescent Dunes apart is its ability to store the sun’s energy in a molten salt mixture that can be used to generate power long after dark.

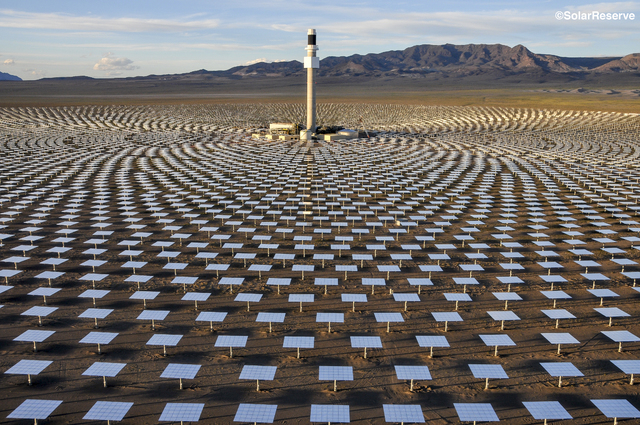

The almost $1 billion project, backed by a $737 million federal loan guarantee, covers about 1,600 acres of federal land — a massive disc of more than 17,000 mirrors arrayed around a central tower nearly as tall as the Washington Monument.

The project employed nearly 1,100 workers at the peak of construction last year. Roughly 200 people now work at the site as it undergoes final testing. A permanent staff of about 40, half of them hired from the Tonopah area, will operate the plant, Smith said.

He called it the first utility-scale solar facility of its kind anywhere in the world, but it apparently won’t be alone for long. SolarReserve hopes to start construction later this year on a slightly smaller, 100-megawatt version of the facility in South Africa.

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Follow @RefriedBrean on Twitter.