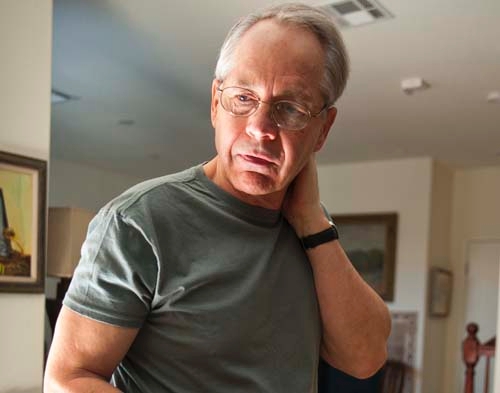

Vietnam vet recalls the night his company was attacked

James L. Kring knew how to pluck a string bass, crash-and-twirl cymbals and bend notes on a trombone.

As a corporal in the 1st Marine Division band, he also knew how to shoot an assault rifle, fire a grenade launcher and defend himself in hand-to-hand combat.

At 22 years old, he was a jazz man at heart and, like all Marines, a rifleman by trade.

He took those skills with him after he finished boot camp with two other guys from his garage band days in a Seattle suburb. On the verge of being drafted, they had joined on the buddy system. But after boot camp they went different ways. Kring became a Hollywood Marine with 3rd Wing Band in Los Angeles.

Then he went to Vietnam.

When he stepped off the plane onto the blistering tarmac at Da Nang in the summer of 1968, the air burned his lungs but inside he felt ice cold and very alone.

“I had just stepped into the war,” he recalled in an interview this month at his Las Vegas home as he flipped through old photos and yellow newspaper clippings.

“That night I didn’t sleep. The sky was black, like the jungle had sucked up all the light. Everything around me smelled like old canvas.”

One of his first gigs was to play a concert at a hospital for the wounded. Afterward, a kid on crutches hobbled up to him with a bandage over his face.

“Corporal Kring,” the kid said. “It’s me, Lubbalie. I came over with you on the plane.”

Kring’s shoulders dropped and the air left his body like somebody had punched him in the gut.

War happens fast, he thought, and as he later learned in the pre-dawn hours of Feb. 23, 1969, it happens with fury too.

At Service Company’s camp near Dai La, about five miles west of Da Nang, rockets rained down routinely. One time at this outpost for 1st Marine headquarters, the screeching sound of incoming forced him to run naked from the outdoor shower and dive into a muddy trench. It made his buddies laugh even though explosions erupted around them.

All fun aside, he thought as a squad leader he ought to hone his skills on the M-79 grenade launcher. One night he fired a round at a target downhill along the barbed wire of the camp’s perimeter. When it exploded, everything went black.

After a brief pause in silence, someone hollered from the valley at the foot of Hill 327. “Kring, you stupid son of a bitch, you blew out our lights.”

Hill 327, which refers to the height of the ridge in meters, or about 1,000 feet elevation, was a target for the Viet Cong and their North Vietnam Army sympathizers because that’s where Marines operated a radar site that supported a surface-to-air missile battery.

In the wee hours of the morning on Feb. 23, 1969, all hell broke loose on Hill 327. Kring soon found himself in the middle of it with the other bandsmen who left their horns behind, grabbed their rifles and headed through a fusillade of screaming bullets for a guard tower that had been overrun by enemy soldiers.

A company of North Vietnamese commandos with suicidal Viet Cong “sappers,” known to crawl into places where Marines were entrenched and explode grenades, had penetrated the perimeter. About three dozen had broken through the wire at a low spot in the ravine between Marine bunkers near guard posts dubbed Alpha 10 and 11. The protected area would soon be infested with enemy combatants.

A gunny sergeant dispatched a truck to haul Kring and his squad to retrieve wounded and retake the towers.

Kring and Sgt. Fredrico Napparan jumped off the truck, looked up and saw a flag, half red and half blue with a yellow star in the center. The invaders had attached a Viet Cong flag to the Alpha 11 tower.

This infuriated Kring. But as he ran pointing his M-16 toward the tower, a satchel charge exploded.

“There was the white flash. Everything turned white and there was a blast of hot air,” he said, recalling how his feet kept running as the explosion lifted him off the ground. The truck was blown on its side.

He landed on his back, unconscious in a patch of 3-foot-tall elephant grass. His hand was bleeding from shrapnel. His face was bloodied and burning from the razor-sharp elephant grass. His legs were like a pretzel with his rifle jammed between them. Its muzzle was stuck in the dirt and its magazine was blown off.

When he came to, he heard movement in the elephant grass.

“There’s feet moving all around me. I hear Asian voices all around me. I hear friendlies yelling and screaming and lots of fire back and forth. They don’t know where I am.”

If he tries to stand up, he would face almost certain death either from the North Vietnamese commandos or Marines who thought he is one of the enemy soldiers.

His only choice is to remain on his back and hold his ground. So, he slid his .45-caliber pistol from its holster with his right hand and released the safety so it was ready to fire. In his left hand, he grabbed the only grenade he had and pulled the pin partially out.

He wasn’t going to die without taking down some of the enemy.

“I’m thinking if I have to, if somebody comes close to me, I toss the grenade, I shoot with the .45 and I start running.”

When he heard feet close by he held his breath. When he had to breathe, he did so slowly through his open mouth so no one could hear air sucking through his nostrils.

“This is my standard response for the next several hours,” he said.

Occasionally, the silence was broken by the pop of AK-47s and automatic weapons. Sometimes he heard Napparan returning fire off in the distance with a grenade launcher.

“The thunder of battle was deafening,” Kring said. “There were hundreds of explosions that night.”

But the scariest moments were when Marine helicopter gunships hovered overhead and fired rockets toward his position at near point-blank range.

“The only real, gut-wrenching shit-your-pants fear is when that (helicopter) came around and started shooting rockets,” he said. “All of a sudden there’s an overwhelming swoosh and then a sudden whine and then an overwhelming explosion. Until you have a rocket coming toward you under 300 feet, you haven’t lived. How do you turn off the sound?”

As the sun rose, the sounds of battle faded.

“I don’t know if our hill was taken over the NVA,” he said, describing how his ears rang so badly that he couldn’t discern whose voices were nearby.

Eventually he determined that the voices were those of American Marines. Then he sat up, dislodged the rifle that was jammed in the ground and put his grenade back in his flak jacket but kept his .45 ready.

“The very first thing I saw was the overturned personnel carrier. Just beyond that I saw a body about 20 yards from Alpha 10. That was the body of Paul Mitchell, the driver.”

A Marine recovery team saw Kring’s bloody face and helped him walk from the elephant grass.

“The first thing I said was ‘That’s Mitchell. That’s Mitchell. You have to let me go to Mitchell.’ ”

But a Marine told Kring he couldn’t go near the body because it might be booby-trapped. Then he looked uphill and saw a dead Viet Cong.

In all that day, 18 enemy soldiers were killed in action and one was taken prisoner. Twenty-nine Marines were wounded and nine were killed in action, including three bandsmen: Cpl. Paul J. Mitchell, of Mahanoy City, Pa; Cpl. John P. Ziegler, of Altoona, Pa.; and Lance Cpl. Victor A. Rabel, of Wheaton, N.M.

Today, on Memorial Day, Kring said he will be thinking about the three, the first Marine band members killed in combat since World War II “and the 58,000 others we lost in the war.”

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at

krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.