The night the lights went out in Las Vegas: Why were the neon signs shut off in ‘73?

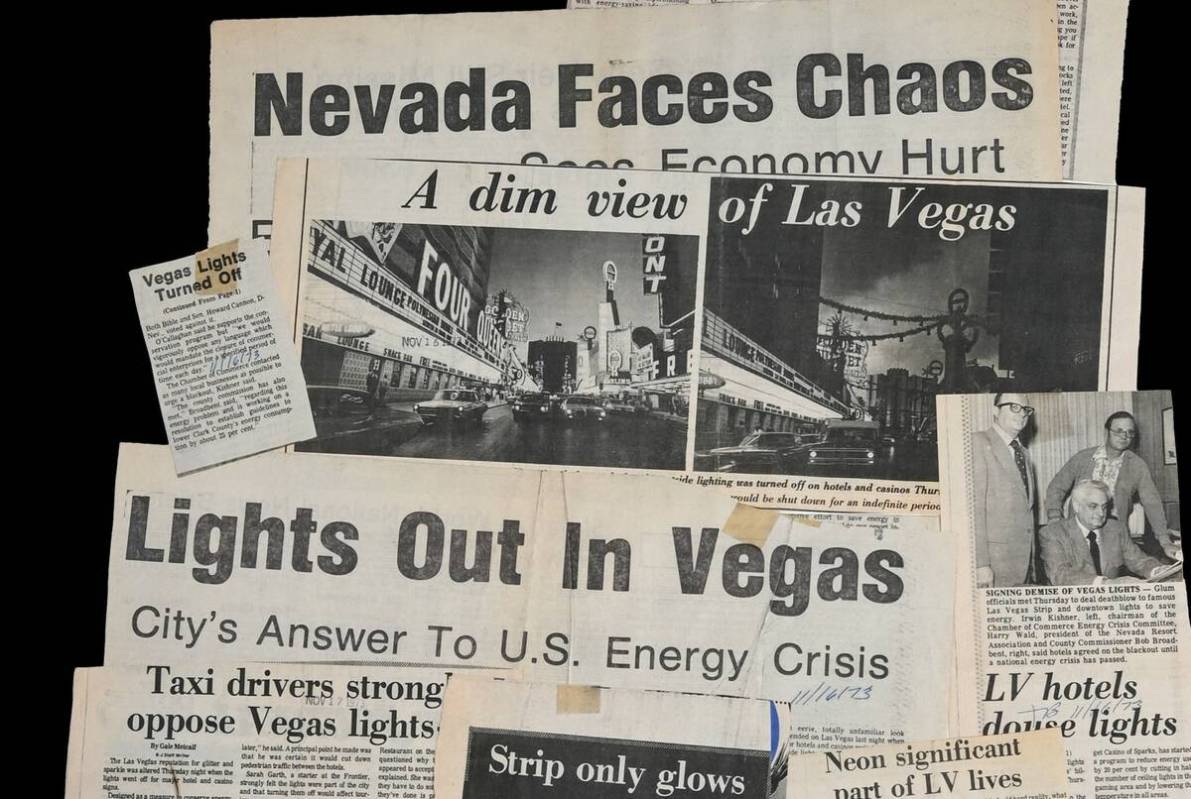

On Nov. 15, 1973, Las Vegas’ world-renowned hotel-casinos switched off nearly all their famous signs and “plunged neon city into an unnatural and spooky darkness,” the Las Vegas Review-Journal reported in a front-page story.

“The splash of literally billions of multi-colored lights heralding each hotel’s tourist attractions were to be extinguished starting Thursday for an indefinite time,” the article said.

But why were the neon signs and most other lights turned off for months on the Strip and downtown in the 1970s?

The move was triggered by the start of the oil crisis of October 1973, when OPEC fuel producers started an embargo to the United States in response to President Richard Nixon’s request to send $2.2 billion in military aid to Israel during the Yom Kippur War, according to federalreservehistory.org.

The drastic cutback in oil deliveries caused the price of a gallon of gasoline at the pump to quadruple, the website stated.

Nixon asked for stringent energy conservation measures across the country, and Nevada Gov. Mike O’Callaghan appealed to the resort industry to cooperate by implementing cuts in power usage, the Review-Journal reported.

Las Vegas officials worried about whether high gasoline prices might discourage the masses of people who visited by car. By December of that year, more than half of the 17.4 million travelers to Las Vegas got there by automobile, according to The New York Times.

Harry Wald, then president of the Nevada Resort Association, held a news conference after conferring in “emergency sessions” with the Public Service Commission and Clark County and city officials, to announce the measures by the Strip and downtown gamers to save up to 35 percent in local energy consumption.

The idea was to conserve fuel, and the fact that the hotel owners took voluntary action was “an outstanding example of civic and community leadership,” Nevada U.S. Sen. Alan Bible said at the time.

‘The message was brought home’

Sounding the alarm, Bob Broadbent, then a member of the County Commission, warned of an “extreme energy crisis,” saying Las Vegas was in “deep trouble” and that its tourism industry was headed for “major disaster” without immediate cuts to energy.

“The message was brought home,” Broadbent said of the governor’s request, “and we have to cut back now or suffer severe losses in our industry.”

Energy conservation in the valley also included a 75 percent cut of billboard lights by three outdoor advertising firms, reductions in indoor heating at hotels, and residents cooperating with pleas to lower thermostats and reduce usage daily during the peak time of 5 to 7 p.m., the Review-Journal reported.

Las Vegas was not the only big energy-using city to order reductions. New York City Mayor John Lindsay stopped short of turning off Broadway, but light usage on 27 movie and theater marquees were cut back and at Times Square, the iconic Coca-Cola sign stopped flashing and the Canadian Club and Sony signs were shut off, according to The New York Times.

Things started to improve that spring. In April 1974, after a long phone call with Federal Energy Administration head William Simon, O’Callaghan said casino lights on the Strip and downtown could burn on Friday and Saturday nights, the Review-Journal reported.

That September, the state Energy Resource Board expanded that to 5½ hours every day, according to the Review-Journal.

O’Callaghan, in an October 1974 statement, said the gaming and tourism business had successfully cut its energy usage by 17 percent, the newspaper reported.

By early January 1975, the neon and other casino illumination were back “to nearly full capacity,” the paper stated.

‘Being part of the effort’

Las Vegas historian Mark Hall-Patton said that, in retrospect, the Las Vegas casino blackout was essentially a “performative” effort for the public, as people were experiencing long lines at gas stations at the time because of fuel shortages.

“If you want to get people’s attention, it’s a great way to get the message across,” Hall-Patton said. “They were doing something to show the industry was being part of the effort to save energy. Did it save much? I don’t know.”

Contact Jeff Burbank at jburbank@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0382. Follow him @JeffBurbank2 on X.