See how Las Vegas has grown over the past 100 years

grown

over 100 years

When architect Bob Fielden moved to Las Vegas in the mid-1960s, downtown was a vibrant place with restaurants, shopping and more, he recalled.

The population had already climbed fast in the once-remote desert outpost, with around 200,000 people living in Clark County at the time. But according to Fielden, people didn’t talk about where the next growth spurts would occur, as they do today.

Fueled over the decades by its ever-expanding casino and tourism industry, relatively low housing costs, near year-round sunshine and lack of state income taxes, Southern Nevada has long been a popular place for people to move to.

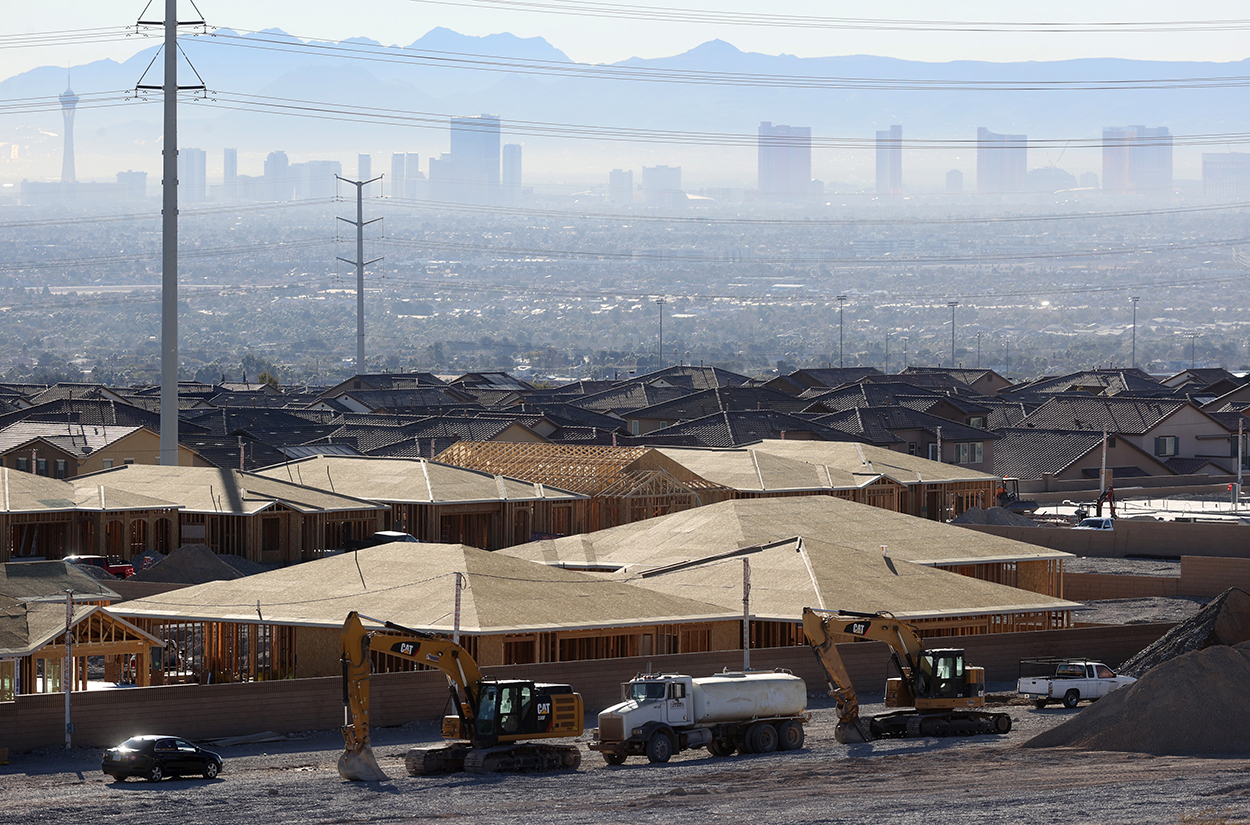

More than 2.3 million people now live in the Las Vegas Valley — a sprawling, still-growing metropolis where homebuilders, commercial developers and others have pushed the boundaries of where people live and work farther and farther out.

“There’s never been a strong sense of community here,” said Fielden, founder of Henderson-based RAFI Architecture and Design. “There’s always been a strong sense of development, a strong sense of growth, and a strong sense of expansion.”

Roughly 3.38 million people are expected to live in Clark County by 2060, up by 1 million from 2020 estimates, according to a forecast last year by UNLV’s Center for Business and Economic Research. Locals often question whether the valley — a heavily suburban market blanketed with single-family housing tracts — has access to enough water to accommodate more people, even with strides made in water conservation.

To illustrate the region’s growth, the Review-Journal has built an interactive map showing when houses, hotels, office buildings, strip malls and other properties were built over the decades. The newspaper analyzed data from the Clark County Assessor’s Office tracking the construction year of buildings on every land parcel in the valley.

If multiple buildings are on one plot of land, only the newest building’s construction date is represented on the map. If a large portion of a building has been remodeled, its age will reflect an average of its original construction date and when it was improved.

Users can hover over the map and see the year the property was built, and zooming in will show the address.

Like other large metro areas, the valley’s oldest real estate is largely concentrated in centrally located areas, while newer buildings are in its outer rings.

“One of the oddities of Las Vegas has been that with almost every census of the 20th century, the population doubled or almost doubled,” UNLV history professor Michael Green said.

Las Vegas’ beginnings

The city got started with a land auction in 1905. By the next year, some 300 people had moved to Las Vegas, with growth fueled by the local rail yard linking Los Angeles to Salt Lake City, Green said.

In the summer of 1929, the Las Vegas Evening Review had a welcome message for visiting Elks club members, noting the city was “a little torn up — but that’s the price of progress.”

The building activity was “but a gesture in the direction of what is to come,” the paper added, with five times as much construction in the pipeline than what was already underway.

For its first several decades, the Las Vegas area primarily grew eastward toward Frenchman Mountain. With America’s entry into World War II, what’s now Henderson took shape as a small factory town to support the war effort, churning out magnesium for munitions and aircraft parts.

The city of North Las Vegas was incorporated in 1946 with less than 2,900 residents, and Henderson was incorporated in 1953 with some 7,400 around that time.

Meanwhile, El Rancho Vegas opened in spring 1941 outside Las Vegas city limits, marking the first hotel-casino in a corridor that would eventually become the region’s main economic engine: the Strip.

Southern Nevada’s population grew fast for decades as more hotel-casinos were built and visitor volume climbed. The valley’s sprawling layout has been heavily influenced by the fact that much of it was developed after the start of the automobile age, UNLV urban affairs associate professor Karen Danielsen said.

Its real estate market then went into hyperdrive during the mid-2000s, as easy money sloshed around for builders and buyers alike, and the valley’s boundaries pushed farther into the desert.

Construction surged, property values skyrocketed, and investors drew up plans for numerous condo towers, a high-rise craze people dubbed the “Manhattanization” of Las Vegas.

Developers also bought huge swaths of government-owned land at auction, for huge prices, on the outskirts of the valley for sprawling new communities.

According to reports, investors bought more than 1,900 acres in Henderson for $557 million in 2004, around 1,700 acres in the northwest valley for $510 million in 2005, and roughly 2,700 acres in North Las Vegas for $639 million in 2005.

Of course, the bubble soon burst, and Las Vegas’ once-bloated housing market was ground zero for America’s real estate woes a decade or so ago.

Property values plunged, construction largely ground to a halt, abandoned projects littered the valley, and people throughout Southern Nevada lost their homes to foreclosure.

The housing market eventually rebounded and, over the past year or so, accelerated with rapid sales, record prices, and plenty of development.

Last year, builders logged just over 12,900 net home sales — newly signed purchase contracts minus cancellations — in Southern Nevada, the most since 2006, Las Vegas-based Home Builders Research reported.

‘Very sleepy town’

Longtime locals often like to say where Las Vegas “ended” when they moved here. Fielden, for one, noted that much of Las Vegas virtually stopped at Jones Boulevard when he arrived, and that Rainbow Boulevard — a mile west — was just a “rural road.”

Both are now major thoroughfares with miles of development stretching west beyond them. “That’s the kind of growth we’ve seen since we’ve been here,” Fielden said.

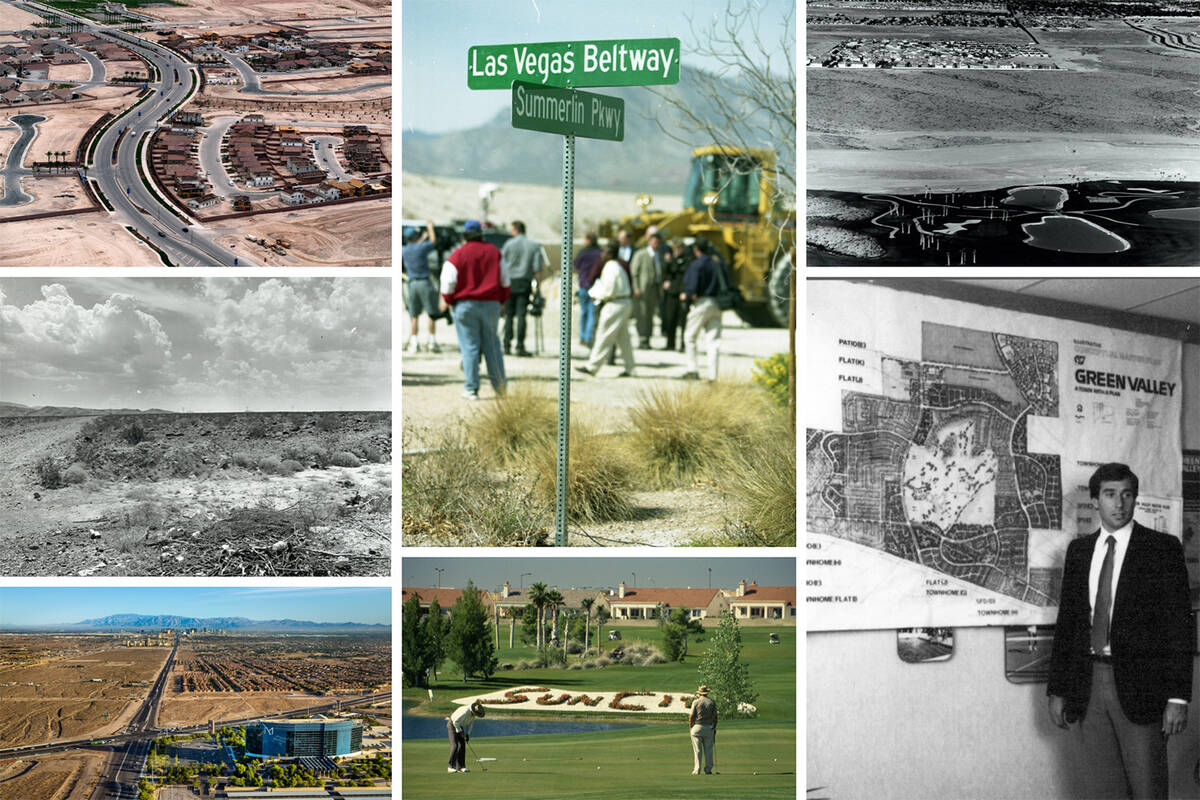

Mark Fine is one of many developers who steered the valley’s growth, helping launch a prominent master-planned community in the eastern half, Henderson’s Green Valley, and then another in the western half, Summerlin.

When he moved to Southern Nevada in 1973, he recalled, it was a “very sleepy town.”

Fine, former president of Green Valley developer American Nevada Corp., guided the community’s growth in the 1970s and ‘80s. The company, founded by his former in-laws, the late Hank and Barbara Greenspun, did not encounter pushback that it was extending the region’s boundaries too far, he recalled.

Instead, landing homebuilders and getting people interested in living there “was our biggest challenge,” Fine said.

The community proved popular soon enough. People started moving to Green Valley by the early 1980s, and by the time Fine left to help launch Summerlin about a decade later, about 800 to 900 homes were being built per year in Green Valley, he recalled.

According to American Nevada Co., as the developer is now known, Green Valley is home to more than 75,000 residents.

Overall, 317,610 people lived in Henderson by spring 2020, up from 24,363 in 1980, federal data shows – an increase of more than 1,200 percent.

Fine was also president of Summerlin in its early years. Spanning 22,500 acres along the valley’s western rim, it started filling in fast, becoming the top-selling master-planned community in the nation for much of the 1990s.

Some three decades after it started taking shape, Summerlin now boasts 100,000-plus residents, a network of parks, trails and community centers, and a commercial core with shopping, restaurants, an ice rink, and minor-league baseball.

Room to grow

Southern Nevadans often gravitate to the newest homes and communities, though Fine noted there’s a limitation to how far the boundaries will go.

Nonetheless, residential developers are still buying land for new projects, and house hunters are buying in new subdivisions throughout the valley.

North Las Vegas accounted for 25 percent of homebuilders’ sales last year, followed by the southwest valley (24 percent), the northwest valley (21 percent), and Henderson (20 percent), according to Home Builders Research.

Lately, one area that’s seen heavy development is along Far Hills Avenue west of the 215 Beltway in Summerlin.

Heading up Far Hills away from the freeway, the area is lined with home construction, and the street dead-ends at Sky Vista Drive, near a new subdivision that sells $1 million-plus houses.

Past barricades and a “NO TRESPASSING” sign off the side of the intersection, construction crews work heavy equipment in the distance, and, pushing toward the mountains, big stretches of desert scrub have been scraped off.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of the Las Vegas Valley construction growth graphic incorrectly categorized the decade in which some buildings were constructed.

Contact Eli Segall at esegall@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0342. Follow @eli_segall on Twitter. Contact Michael Scott Davidson at sdavidson@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3861. Follow @davidsonlvrj on Twitter.