River Rats, still healing, gather in Vegas near 40th anniversary of Vietnam War

They huddled at a Las Vegas resort to reflect on what their minds can’t erase nearly 40 years after the end of the Vietnam War.

About 25 River Rats — men who wore black berets in the brown-water Navy and fired machine guns from fast-moving boats and low-flying helicopters over the Mekong River delta — reunited last week for the 12th time since the war ended April 30, 1975.

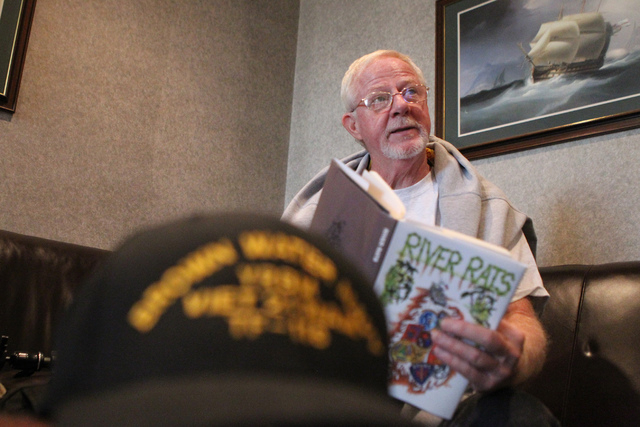

“We’re still in the healing process in many ways. Vietnam has not left us,” said co-organizer, author and river patrol boat veteran Ralph Christopher, of Las Vegas. At 64, he is the youngest of the group. “The reunion is really about helping my guys come back together.”

In 1970 alone, five years before South Vietnam’s capital, Saigon, fell to communist North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces, nearly 100 sailors of the brown-water Navy were killed in action or died of wounds. They were among more than 2,570 Navy war dead from 1960 until 1975, according to the group’s historian, retired Chief Warrant Officer-3 Ralph J. Fries.

One who survived a 1966 River Patrol Force battle, Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class James Elliott Williams, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions in a battle to defeat Viet Cong guerrillas.

Fighting the Vietnam War “was 10 minutes of pure hell; an hour of frustration; and the rest of your day was spent wondering, curious as to whether or not you were going to be alive 24 hours from now,” said veteran Petty Officer 1st Class George Wendell, 65, of Las Vegas.

“Sixteen of us trained together as a team. In a year’s time, four of us returned home, two walking, two in a chair,” Wendell said. “The war itself was very ugly. But the country and the people are very beautiful, very open, very friendly.”

Nevertheless, he said, “I won’t ever go back there, because there are too many memories there, too many bad memories.”

Christopher, who has returned twice to Vietnam, said, “We weren’t fighting for President Johnson, President Nixon, Mom, apple pie. We were fighting for the guy on the left and the guy on the right for the right to return home someday, go back to school and pick up our lives.

“We were the group that didn’t run and burn our draft cards. We answered the call.”

CAMBODIA AND KENT STATE

Christopher, who manned .50-caliber machine guns, endured four deployments from 1967 to 1970. He was one of the River Patrol “Gamewardens” in Task Force-116. They patrolled rivers and canals in 31-foot fiberglass boats to assist the U.S. Army in severing supply lines and intercepting Viet Cong scouts and North Vietnam Army infiltrators along a 200-mile stretch of the Cambodian border.

“There would be hundreds of little boats out there manning .50s, hiding in the bushes, and here comes the NVA down the trail, 1,000-strong carrying guns and arms. They had to get by us. We were the first to greet them.

“Some nights they made it. Some nights they didn’t. They were warriors. I didn’t like their politics but they didn’t cry. They fought and died like men. I think many of them were young like us,” Christopher said Wednesday, where the River Rats gathered in suites at The Orleans.

It was the Cambodia Incursion, or counterinsurgency campaign, that sparked protests that led to the Ohio National Guard shootings of four anti-war demonstrators at Kent State University.

“I’ve always felt that they did not truly understand what the mission was,” he said about the protesters. “They confused us with invading a country illegally, when the truth was the Cambodians were begging us to come in and help them.”

For months the River Rats had watched bodies float down the Mekong River. “There was a genocide going on in Cambodia in mid-’70, and they were killing these civilians and throwing them in the river.”

The brown-water Navy with its heavily armed boats and Seawolf helicopters “saved a lot of lives,” Christopher said. “We pulled 70,000 refugees out of Cambodia and housed them on the side of the river in Vietnam at a Red Cross camp.”

Meanwhile, the role of U.S. forces shifted to training the South Vietnamese to defend themselves. During the 1970 campaign, 300 American lives were lost, but the South Vietnamese military death toll was 10,000.

“We lost no war,” Christopher said. “We turned over our war machines, our boats, and we were told to let them take the lead. … You can’t count 1,000 Marines at the embassy or a couple thousand advisers as a major force when you’re taking on half a million communist troops.

“So we weren’t there in ’75. So the idea that we lost some war, it’s like saying, ‘I lost Gettysburg.’ I wasn’t there,” he said. “I had come home. All my buddies had come home. We were sitting in front of the TV like everybody else when we watched the tanks roll down to the embassy.”

SWIFT BOAT SAILORS, SEAWOLF SHOOTERS

Gary Ely, 66, of Lakeside, Calif., turned 21 during his tour from January 1970 through August 1971.

Trained as a Navy structural aircraft mechanic from Des Moines, Iowa, he became a gunner for a helicopter attack squadron. He manned .50- and .60-caliber machine guns, and door-mounted mini-guns.

“Shooting a hand-held machine gun out the door of a helicopter is pretty exciting no matter what you’re shooting at. It was even more exciting when you’re helping the guys on the ground eradicate the enemy,” he said.

Regardless of opinions on winning the war, Ely said, “All I know is a lot of guys came home after the war, and some of them wouldn’t have if I hadn’t done my job over there.

“For me it was a job I did while I was in the service. I don’t carry any baggage with it right now. I didn’t carry too much baggage back then.”

He views the 40th anniversary as “an opportunity to look back over my shoulder.”

“I take quite a bit of pride in the fact that I did fight in that war even though it was as unpopular as it was.”

Part of their job was covering for swift boats when they came under attack on missions to transport Navy SEALs and hunt down enemy soldiers lurking along the banks.

Swift boats were 50-foot long, 12-foot-wide mini battleships made of aluminum, one-fourth-inch-thick, that could run rivers in the Mekong Delta at 30 mph.

James Steffes, 73, a retired engineman chief from Sun City, Calif. — whose hometown is St. Cloud, Minn. — was a senior petty officer, second in command on four boats during the war. He was stationed in Hawaii when Saigon fell.

“It was like somebody hit me between the eyes,” he said, adding, “It seems like winning wars is no longer an American dream.

“When you talk about the 40th anniversary, at the time where the previous history was World War II, which (we) won; Korea, which (we) pretty much defeated them, and they didn’t surrender,” Steffes said.

“So Vietnam was really the first one that we fought for years and years and years, and then kind of walked away and it was fought in an ally’s country against a guerrilla war,” he said.

“So as upset as we felt about it, if you look back on those 40 years now, they’ve done the same thing in Afghanistan, and they’ve done the same thing in Iraq and other parts around the world where they don’t want to win any more.”

Steffes, a member of the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, took issue with former Navy officer and now Secretary of State John Kerry when he ran for president of the United States.

“We objected to the fact that he said out of the 2½ million people who served in Vietnam all of us were baby killers and burning crops and stuff like that,” he said. “I never saw any of those things. His idea of raping and pillaging the land like Genghis Khan, it just didn’t happen.”

Said Wendell, a swift boat engineman: “I was disappointed then, and I’m still very disappointed today in the way our government handled the situation.

“It would have taken just one major, concentrated military push, and it wouldn’t have been a U.S. surrender and a South Vietnamese surrender. It would have been North Vietnam surrendering. But politicians and egotists back here in the States changed all of that.”

Tom Restemayer, 67, of Camano Island, Wash., enlisted at 17 out of Cavalier, N.D. He earned two Purple Heart medals as a gunner’s mate 3rd class.

A message written on the back of his shirt sums up his thoughts: “Vietnam. We were winning when I left.”

“I just tell people we didn’t lose the war. Our politicians lost that war, because they were afraid of the protesters. They didn’t care about the enemy,” Restemayer said.

GOOD TIMES AND BAD

More than 30 sailors in Restemayer’s unit lost their lives battling for control of the Vam Co Dong River.

“Adrenaline does strange things to you,” he said. “Once you start getting shot at, that adrenaline kicks in and all you’re thinking about is defending your boys.”

In one nighttime battle with the patrol boat anchored, tracer bullet fire erupted from both banks.

“You could read a book by the tracers,” he said. “I finally ran out of bullets.”

He reached on the deck and scrounged up one belt that had five rounds left to take out the last threat from an enemy Sampan.

River patrols often reached out to South Vietnamese fishermen and farmers to win their hearts and minds by giving them fishing gear and sacks of rice and potatoes and ensure their goods got to the free market rather than face the wrath of communism.

Many Vietnamese have since thanked them for saving lives and property.

Christopher was sitting on a grenade box listening to Grand Funk Railroad play “I’m Your Captain” on his 8-track player, when he learned he was going home.

With the sun beating down, the dress code meant it was OK to wear shorts and sandals with a holstered .45-caliber pistol. “We looked like McHale’s Navy,” he said, referring to the 1960s TV comedy about a World War II Navy PT boat crew.

In his 2005 book, “River Rats,” Christopher recalled his mixed emotions, like he had just hit a royal flush but couldn’t tell anybody because he felt bad about buddies he was leaving behind.

“Most of us just wanted to return home and pick up our lives and go to school on the GI Bill. However, I am very proud of the River Rats and it was my honor to try and bring their stories to the world,” he said.

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Find him on Twitter: @KeithRogers2.