‘One pill will kill’: Mother hopes billboards will save others after son’s death

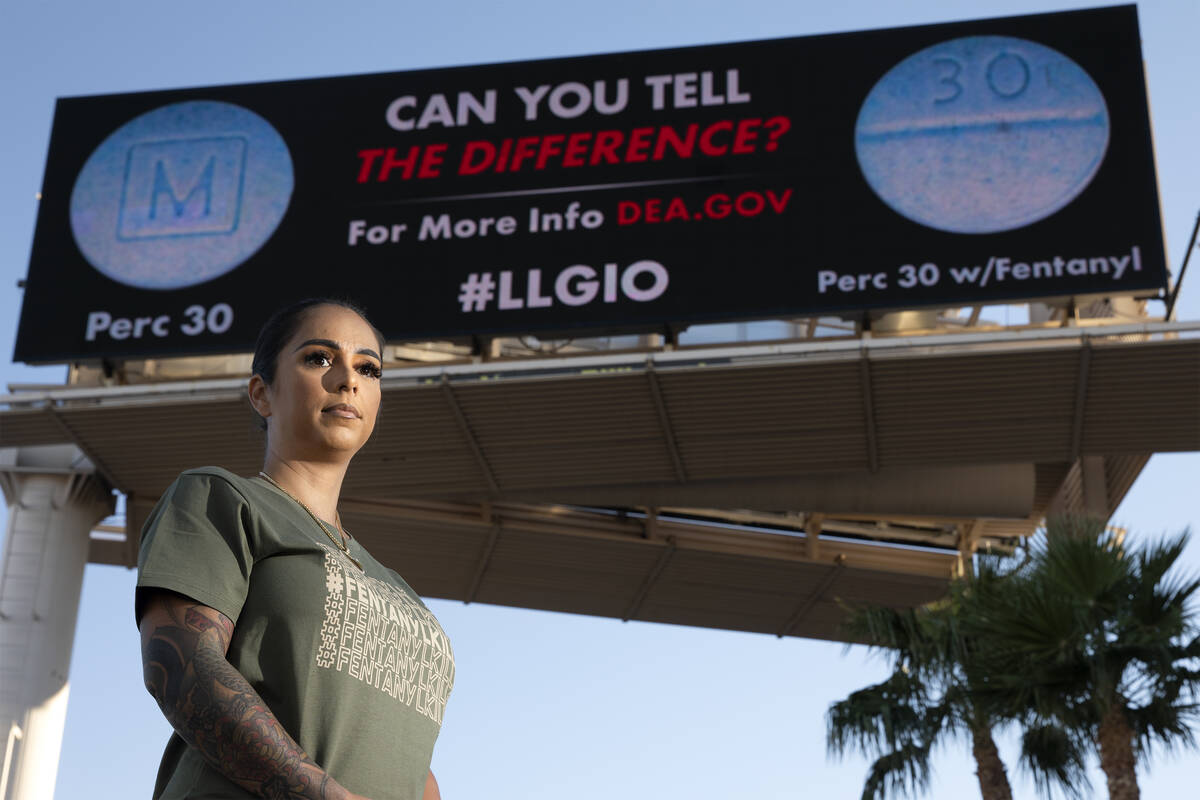

Calling fentanyl the “Fastest, Deadliest High,” billboards along Interstate 15 flash alternating images of the powerful synthetic opioid in powder and counterfeit prescription pill forms.

The next image shows a smiling Giovanni Perkins with the words “ONE PILL WILL KILL” underneath his photo.

To most motorists, the radiant teenager from Henderson is a stranger.

Not to Cristina Perkins.

“When I see the one with his face, you know, I still think ‘That’s my boy,’ ” she said, stifling a sob as she stood underneath one of the billboard days after they went live Oct. 22, on what would have been her eldest son’s 19th birthday.

Giovanni Perkins died in 2020 after taking a counterfeit Percocet pill laced with fentanyl, his mother said. The Clark County coroner’s office ruled his death an accident from fentanyl intoxication.

Known as “Gio,” the 17-year-old was described as a playful and affable boy with an infectious laugh.

He was one of 106 Nevadans younger than 25 who died of drug overdoses in 2020, nearly three times as many as the previous year, according to a report from the state Division of Public Health and Behavioral Health.

Law enforcement officials say that fentanyl — considered to be up to 100 times stronger than morphine — is killing unsuspecting victims who think they are taking prescription painkillers, such as oxycodone, Adderall and Xanax.

“A microgram of (fentanyl) can kill you, and we need people to realize that,” Clark County Sheriff Joe Lombardo told the Las Vegas Review-Journal in December. “They don’t quite often know what they’re buying on the streets.”

Deaths rising

Fentanyl was blamed in 219 deaths in Clark County last year, a surge from 74 reported in 2019, Metropolitan Police Department data shows.

Through October 2021, the synthetic opioid had killed 208 people, about a 15 percent increase from 2020’s already high figures, according to the data.

Gio was one of 10 minors to die from a fentanyl overdose in Clark County in 2020, an increase of nine from the previous year. In 2021, six minors had died from the opioid through October.

“I wholeheartedly expect the problem to get worse,” Lombardo said.

Metro’s Overdose Response Team includes members from the Drug Enforcement Administration and the Clark County coroner’s office. The task force is increasingly pursuing murder charges against drug peddlers.

“It’s like pushing back on the ocean,” Lombardo said. “We have to do it a piece at a time, and we can’t turn a blind eye to it and ensure we’re being proactive.”

Education is key to eradicating the epidemic, Lombardo said, noting that “we rely on parents, too.”

Although it was too late to save her son, Perkins has made it her life’s mission to keep others from feeling her pain.

“I just researched, I researched and I researched until I couldn’t read no more,” she said about fentanyl, which she knew nothing about prior to her son’s death. “I researched until I couldn’t watch enough videos.”

She then raised nearly $18,000 on GoFundMe to rent 10 billboards across the valley for six months. She hopes to raise more money to extend them at least six more months.

“We figured, if we put up billboards, even if you don’t know our family personally, possibly you drive by it and you see it, you know, you can be curious and hopefully Google it and research it yourself,” she said.

‘It was too late’

“That whole morning is a blur,” Perkins said of Aug. 28, 2020.

She was in bed when Gio’s panicked girlfriend ran into her bedroom, saying something was wrong.

The couple had planned to attend a “senior sunrise event,” but he was not waking up.

Perkins does not remember who called 911, but a dispatcher instructed them to lay the teenager on the floor and begin chest compressions.

“I felt like I was doing it for 100 years,” Perkins said.

The paramedics arrived minutes later, but deep down, she said, she knew her son was dead.

“You’re trying to bring your child back,” she said. “But in my head, I knew it was too late.”

Gio’s best friend since grade school, Mason Atkins, got a call that morning and rushed to Perkins’ home.

“My mind just started spinning,” the 18-year-old said in a phone interview.

Gio was enrolled in Desert Oasis High School and was about to transfer to Odyssey Charter School to graduate early that December.

He enjoyed working at a car wash with friends — so much so that Perkins’ parents had talked about helping them start their own business.

Although Gio was reaching adulthood, Perkins envisioned him living with the family for a few more years while he figured out what he wanted to do in life.

At a memorial balloon release for Gio, a young man walked up to Perkins and told her that her son had stood up for him when he was being bullied.

“If I didn’t know Gio,” said Atkins, sobbing, “bringing me into his family and making me feel like I was a family member, I wouldn’t like the music I do, I wouldn’t act like I do, I wouldn’t dress how I do. Gio influenced it all.”

People have told Perkins that “it will get better.”

“It doesn’t, not one bit,” she said.

She foresees the end of every year being the hardest: Gio died in August, his birthday was in October, and family-oriented holidays followed.

She described it as time with nothing to look forward to.

“You just have to cry it out,” she said. “You gotta let it out.”

Contact Ricardo Torres-Cortez at rtorres@reviewjournal.com. Follow him on Twitter @rickytwrites.