Las Vegas’ first Black police officer honored for historic career

Herman Moody would regularly tell his young children that “your reputation enters the room long before you do.”

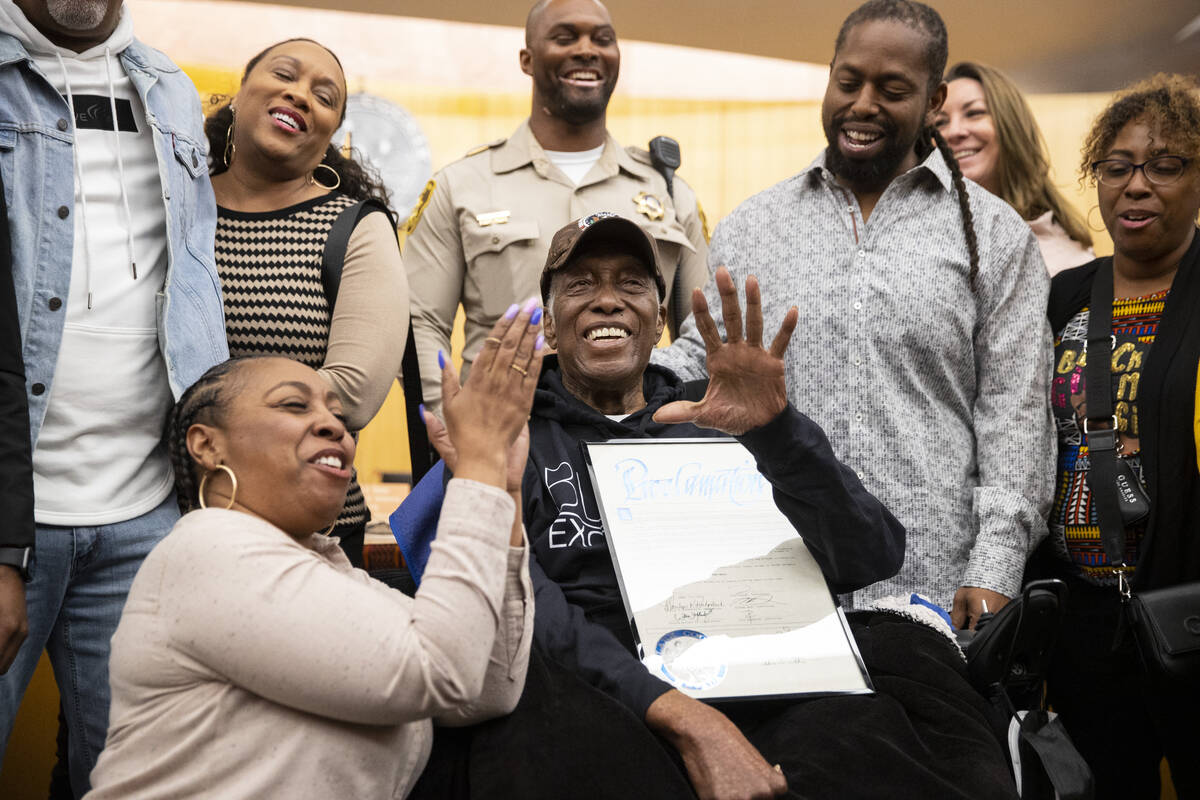

That was the case Tuesday morning when 97-year-old Moody appeared in front of Clark County commissioners, who issued a proclamation, honoring his 31-year career as the first Black police officer in Las Vegas history.

At his age, the Navy vet who served in World War II gets emotional talking about his time in law enforcement, his daughter Tracey Hayes said.

So, she spoke for him.

“We’re very humble today,” she told the packed room, which comprised loved ones, officials and a cadre of cops. “He’s very humble today, and if he could speak for himself, he would, but he would have you here all day,” she added among laughter.

But while Moody stayed mostly quiet, his wide, beaming smile as he waved at the crowd did the talking.

Metropolitan Police Department officers — accompanied by a Regional Transportation Commission of Southern Nevada van with a wheelchair lift — picked up Moody from his house and took him to the Clark County Government Center.

“I’ve said before and I’ll say it again,” Commissioner William McCurdy II said. “It is so important that we honor and give flowers to those who have laid the foundation and paved the way for so many of us. And I’m glad that Mr. Moody is going to get his flowers here today.”

Afterward, the procession headed to nearby Metro headquarters where a plethora of uniformed officers, many of them Black, greeted him in the courtyard. Moody shared a quiet moment in front of a classic cruiser similar to one seen in a photo displayed during the ceremony. In that shot, the younger Moody leans against it in a smiling pose.

Some of Moody’s police tools were on display in the lobby, including his belt, a log book, and more photos, a Metro spokeswoman said.

He met privately with Metro’s executive staff and more officers who dropped by to say hi, Hayes said.

“I’m happy that he’s with us and was able to take part in it, and enjoy it,” Hayes said later over a phone interview.

Historic career

Herman Moody’s family relocated from Arizona to what is now known as the Historic Westside in the late 1930s and built a home. He attended Las Vegas High School, where he participated in sports.

He later built his own house in the neighborhood, where he and his wife, Magnolia, raised a family. They share five children, six grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. Magnolia Moody died 16 years ago after 56 years of marriage, Hayes said. She was a retired juvenile probation officer.

When he returned from the war, Moody wanted to become a diesel engineer, but the school where he planned to attend had no openings.

In a 1976 interview with the Las Vegas Review-Journal shortly before he retired, Moody said he initially had reservations about going into law enforcement, which he thought would remind him of the military.

“It was just by accident I became a policeman,” he said, crediting sports for his physical ability.

He joined the force in 1946, when officers had to provide their own gun and uniform. The police academy did not exist.

So he borrowed the tools of the trade, and taught himself about Nevada law and the court system.

Moody described a rough first few days. But it was not long before he was fully committed.

“You dedicate your life to the cause of humanity — to serve the people,” he told the newspaper. “You can’t forget the thought (that) you’re the servant of the people.”

When the engineering school was ready to take him in, “I decided to stay,” he said.

As the department hired new Black officers, Moody hosted training sessions at his home multiple times a week using the same books that he had read to teach them about the craft.

Three years after he was hired, he became the first Black motorcycle officer in the department’s history. He later shifted to detective work in the units that probed narcotics and theft, before he retired while he was in Metro’s fugitive detail.

When the police department and the sheriff’s office consolidated into the Metropolitan Police Department in 1973, Moody was the second most senior officer in the agency, earning badge No. 2, Hayes said. More than 20,000 officers have come and gone from Metro since, she added.

Throughout his career, his guiding light was the ethics of policing.

“I have found, if the principles of the department are reflected in the community, then a man can be a policeman in any community he wishes to be,” he said in 1976.

Asked in the same interview about being a Black cop and not promoting past his unranked detective position, Moody said that he had passed the tests needed to be promoted. And that although he was never told explicitly, he got the impression that Metro was “not ready” for a “Black officer of rank.”

Still, he said he felt no resentment and credited fate for his prosperous career.

“Maybe if I’d made sergeant or lieutenant, I might have lost the concept,” he said. “I’d never want to lose that moral concept.”

His daughter said he has a framed copy of the article hanging at home.

‘Inspiration’

Metro officer Arnold Parker remembers growing up a couple of blocks away from his great uncle and the “Moody house.”

“He’s someone that I would say our entire community and our family look up to,” said Parker, noting that people during that era likely doubted a Black American could flourish in law enforcement.

“He pretty much defies those odds, and makes that statement incorrect,” Parker said.

Moody was part of the reason Parker chose his career.

“It’s important to know, ‘Hey, any kid that grew up in Vegas, no matter if you’re Black or any color, you could accomplish any dream that you want,’” Parker, 40, added.

Two of his daughters, Hayes and her sister Seona Jefferson, also worked for Metro as civilian employees.

Although Tracey Hayes’ husband, retired Metro Sgt. John Hayes, did not work with his father-in-law, the veteran was known as a legend.

“I always knew who he was,” he said.

Moody has a “wealth of information” that gives hope to others to follow in his footsteps, the retired sergeant said.

Tracey Hayes said that the honor for her father was “long overdue.”

To see other young, Black officers “lifted his spirits and he could see the fruits of his labor,” she said about her father.

“It really touched his heart,” she added. “All in all he had a really good day.”

Contact Ricardo Torres-Cortez at rtorres@reviewjournal.com. Follow @rickytwrites on Twitter.