Historic Jackson Avenue once was Las Vegas’ ‘Westside Strip’

It’s been more than 50 years, but John Edmond can list the places as though he’d driven by them yesterday.

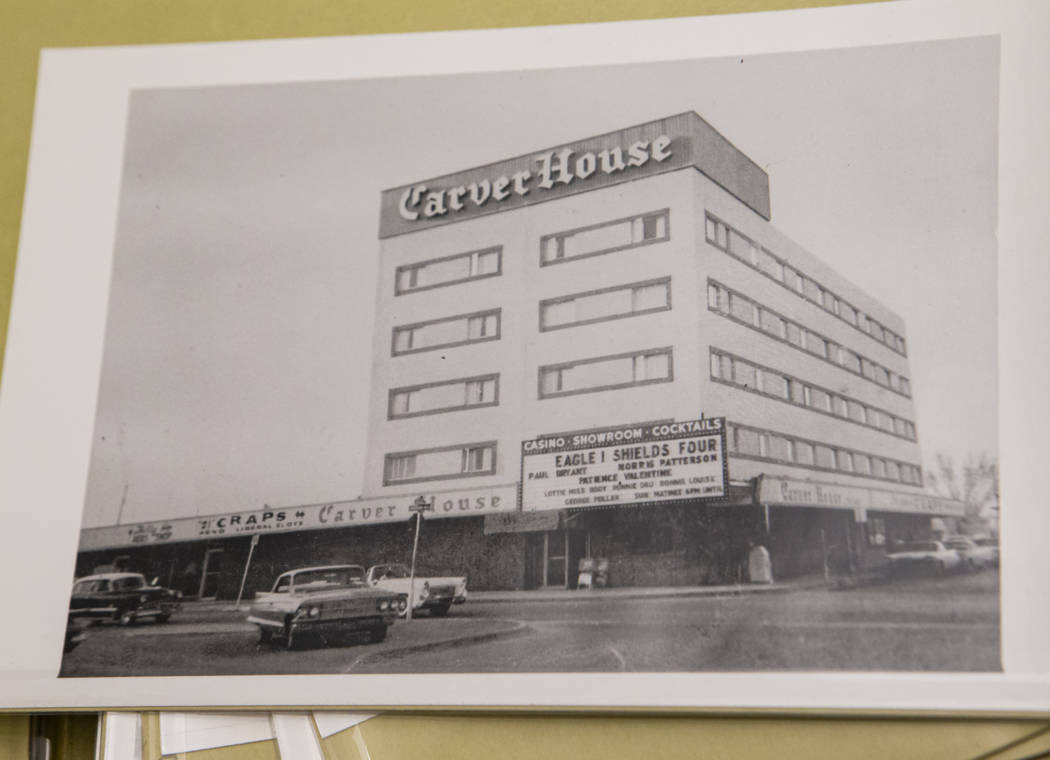

The Carver House at D Street and Jackson, the Jackson Hotel across the street and the Cotton Bowl, the bowling alley where he once worked as a pinsetter, at Jackson and E Street. Mom’s Kitchen and the barber shop next to that. Hick’s Bar-B-Q and Johnson’s Malt Shop, and Sammy Lee’s pool hall, where Edmond and friends would hang out as teenagers.

“You had all those places on Jackson Street,” Edmond says. “You had all that activity right there on Jackson.”

It’s hard to believe nowadays, when Jackson Avenue is a mostly deserted stretch of pavement peppered with houses to the east and vacant lots and old buildings the rest of the way. But from the ’40s through the mid-’60s, Jackson was a main artery through what used to be called west Las Vegas (now known as the Historic Westside) and a thoroughfare populated with enough clubs, bars, restaurants and nightspots to earn it a nickname as the Westside Strip.

Clark County has its Strip. Las Vegas has Fremont Street. And for a few memorable decades, west Las Vegas had Jackson Street.

In the beginning

Jackson Street — technically Jackson Avenue, although most who remember its heyday seem to favor “street” — and the neighborhood in which it sits were born largely from segregation.

During the early ’30s, African American residents “left downtown and moved across the tracks, because the mayor at the time said if they did not move they could not get a business license,” says Claytee White, director of the Oral History Research Center at UNLV Libraries.

“This was the time when African Americans could not enjoy the Strip. You could work in the back of the house, meaning that you could be the porter who cleans the floors, or you could be a maid or you can work in the linen room. And you had to go into the back of the casino. You could not enter the front door.

“Even some of the early entertainers. Sammy Davis Jr. in the beginning could not enter the front door, either. They had to go in from the kitchen area into the casinos. And, then, of course, after the performance was over, you had to go back to the Westside.”

Against that exclusionary backdrop, Jackson Avenue “presented entertainment,” White says. “It allowed the African Americans in the city to mingle, and they could mingle with each other and with the stars who were in town.”

A historical marker on Jackson Avenue — the street’s only visible evidence of its lively past — notes that, in 1942, a commercial district was established from D to F streets along Jackson and Van Buren. Permit requests in 1942 encompassed such neighborhood necessities as a grocery store, a barber and a beauty shop, restaurants and a gas station.

From that nucleus, other businesses and services of the sort any neighborhood needs began to take root along Jackson and the streets around it. Among them were small casinos, clubs and music venues.

“You have to understand that this was the only place black people could go,” says filmmaker Stan Armstrong, who grew up in west Las Vegas. “Blacks weren’t allowed to go to the Strip, so the only place they had to go was Jackson.”

Childhood memories

Jackie Brantley grew up on Van Buren, about a block from Jackson. She recalls west Las Vegas then as a village within a village where everybody knew everybody. She remembers seeing patrons visit Jackson Street nightspots dressed in mink stoles and hearing about Pearl Bailey and Sammy Davis Jr. stopping by to unwind — and even perform in impromptu jam sessions — after doing their shows on the Strip.

Brantley remembers hearing the music from the clubs from her front yard and, at age 12, seeing James Brown perform at Jackson Avenue’s Elks club.

“I was standing right in front of the stage and his sweat hit me in the face when he was doing one of those twirls,” she says. “I wasn’t in heaven. I was beyond heaven.”

Jackson Avenue’s patrons weren’t just African American. “We would see tons of white people in cars, strolling up and down the street,” Brantley adds. “Let me tell you, it was integrated.”

It made for a vibrant, exciting time, Brantley says. “If you thought for one minute the Westside was boring, you were so badly mistaken. That’s what surprised people. They’d come here on the Westside and expect to see rundown businesses and rundown houses. There were so many Cadillacs on the street and people walking back and forth dressed to the nines.”

Jackson and the streets around it also made up west Las Vegas’ economic hub. “It would be like driving down to The District today,” White says. “You’d have clothing stores, restaurants, beauty shops, everything right there.”

There was a music store where Sonny Liston and Muhammad Ali would hang out, says Armstrong, who has heard stories about how “Sammy Davis Jr. would go from one bar to the next and lose his money playing craps and always get a free meal at Mama’s Kitchen.”

Cruising Jackson

“A lot of African Americans felt comfortable on Jackson Street,” Armstrong says, because it reminded them of the places they knew back in Fordyce, Arkansas, or Tallulah, Louisiana.

Edmond, who lived near G Street and West Washington Avenue, says that “as curious teenagers with nothing to do, of course we’d go (to Jackson Street) for the night and just hang out.”

Jackson Avenue and west Las Vegas offered so much — an ice cream place, a pool hall, plenty of interesting people to watch — that it never was boring, he says. “As a kid, I didn’t miss anything. Everything you wanted to do, it was right there in the neighborhood.”

Still, Jackson Street wasn’t perfect.

“Unfortunately, what you’re missing are a lot of city services,” White says. “You don’t get paved streets till the ’50s. I think sewage (service) was the same time, in the ’50s. Streetlights, all of the things that the city takes care of, (it) did not take care of in the African American community.”

Integration’s effect

Ironically, the advent of integration contributed to the dimming of Jackson Street’s lights. As segregation on the Strip began to disappear during the early ’60s, African American residents’ options — for where to work and live and have fun — expanded, White says.

“You had middle-class and upper-class blacks who couldn’t live anywhere else prior to that could now move out and live in other places. There were lawyers and doctors and school teachers and businessmen by this time. So you have a whole gamut of people, just like in any neighborhood, who could move out and live where they wanted to live. Some of them took advantage of that and others didn’t.”

After 1960, no longer restricted to seeking goods and entertainment solely in west Las Vegas, “you see that trickling of the community beginning to go to the Strip,” White says.

But the story of Jackson Avenue’s past is about more than nightspots and restaurants. Rather, White says, “when segregation did not allow equality and inclusion, that was the place that it happened.

“We need to know about it because it’s important to see what a community can do all by itself. No help from banks, no help from the city, no help from anybody, and (residents) not even having the kinds of jobs that (they) were entitled to. Even in the face of all this, the community still rallies and becomes a place where the cultural aspects of the community are made possible.”

Contact John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280. Follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.