Father and son died on the same day, 14 years apart while working on Hoover Dam

Tuesday marks a somber date in Sharon Tierney’s family history, and she plans to observe it the way she usually does.

Each year around Dec. 20, the Nevada City, California, woman delivers fresh flowers to the grave of her beloved great-grandmother. Then she spends the rest of the day remembering two men she never knew who “died to make the desert bloom.”

Even after 81 years, stubborn myths still cling to the colossal construction effort that built Hoover Dam. Despite what you may have heard, no workers are entombed in the concrete structure. The hardhat was not invented there.

But the most incredible story about the project is absolutely true.

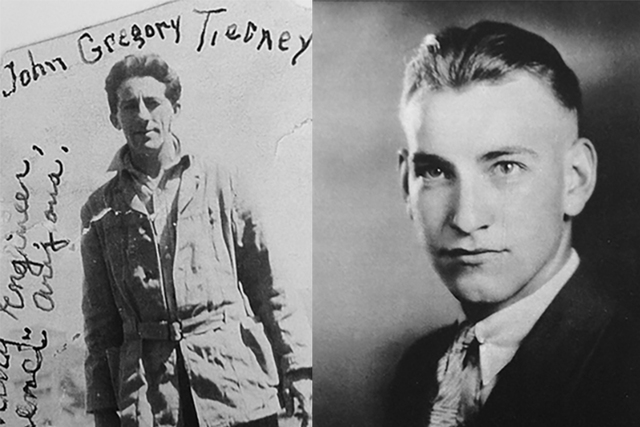

On Dec. 20, 1921, a crew surveying locations for the dam got caught in a flash flood, and a man named John Gregory Tierney was lost forever in the raging Colorado River, one of the first casualties of the project. Then on Dec. 20, 1935, 14 years later to the day, the job site suffered its last fatal accident, when a worker fell to his death from one of the two intake towers on the Arizona side of Black Canyon. That man was Patrick William Tierney, J.G. Tierney’s only son.

Their names appear in raised metal on a plaque near the dam, never to be forgotten.

Sharon thinks the name Marie Elizabeth Tierney Sherer also belongs on a plaque somewhere.

“To me, she’s the story. Here she lost her husband and her son on the same date,” Sharon said of her great-grandmother. “She had a hard time about it the rest of her life. She was always very quiet on Dec. 20.”

‘THE WORK WILL GO ON’

John Gregory Tierney, or J.G. for short, was born May 20, 1885, in Piedmont, Missouri, the sixth child in what Sharon Tierney called a “very strong Irish Catholic family.”

Like his namesake Irish grandfather, he made his career as a hard-rock miner — work that would carry him to Idaho, then Arizona and finally to a survey camp on the bank of the Colorado River in Boulder Canyon.

According to family lore, J.G. and Marie met on a train during her return trip to boarding school after the holiday break. She never made it back to school.

The two were married on May 7, 1909, when she was just 15. Their son, Patrick, was born the following summer in St. Louis.

The couple later had a daughter named Alice, but she contracted measles and died at 3 while the family was living in the southeastern Arizona mining town of Morenci, Sharon said.

Not long after that, the Tierneys moved to northwestern Arizona, where J.G. found work with the survey crew searching for a suitable spot to dam the Colorado.

It took almost two weeks for the news of his death to reach Las Vegas from the remote work site.

“The Colorado was just an unfettered river all the way from the Grand Canyon to Yuma,” said historian Dennis McBride, director of the Nevada State Museum in Las Vegas. “It would have been a wild river with terrific flooding.”

Newspapers offered differing accounts of what happened, but the endings were the same: J.G. disappeared into the water and his body was never found.

It haunted Marie that her husband never got a proper burial, Sharon Tierney said. “Every time a skeleton was found along the river, she would make an inquiry to see if it was him.”

Walker Young, the engineer in charge of the dam project, had this to say about the accident in the Jan. 6, 1922, edition of the the Clark County Review newspaper: “When Tierney lost his life it completely demoralized our forces. The rising Colorado River has made the work extremely hazardous and about 15 of our men quit immediately. However, they will be replaced and the work will go on.”

IN HIS FATHER’S FOOTSTEPS

Patrick William Tierney was 12 when he lost his father to the Colorado and his grief-stricken mother moved with him back to Missouri.

This time they settled in the Springfield area, where Patrick went to high school and met a girl named Hazel in an archery club.

The couple married in August 1931 and welcomed their only child the following year: Patrick Gregory Tierney, Sharon’s father, born July 20, 1932.

Not long after that, the three of them headed west in search of work in the deepening Depression. The dam was the biggest construction project going, and Patrick may have thought he could parlay sympathy over his father’s death into a job there.

His mother didn’t like the idea. “She didn’t want him there. She was concerned,” Sharon said.

She recalls reading some of the letters Patrick sent to his mother describing conditions in Black Canyon — the hard work, the hot weather and the steep terrain. Sharon described him as an aspiring writer learning to be an electrician.

According to newspaper accounts, the 25-year-old electrician’s helper fell 320 feet from one of the two intake towers on the Arizona side of the dam. His body was recovered several hours later from about 25 feet of water on the upstream side of the dam, where Lake Mead was beginning to fill.

The Las Vegas Evening Review-Journal was the first to connect the deaths of the two men. In its Dec. 21, 1935, edition, the paper reported that Patrick Tierney’s widowed mother had been scheduled to arrive in Boulder City on Christmas Eve to spend the holiday with the family.

Hazel took the $100 death benefit she received from the project and returned to Springfield with her 3-year-old boy to bury her husband.

Sometime after that, Sharon Tierney said, Hazel, her young son and her mother, Vera Hart, packed up and moved to Oregon, where the women built a cabin near Portland and started a business selling homemade pies to loggers.

“I have a long line of strong women in my family,” said the 63-year-old retired paramedic firefighter.

Both Marie and Hazel eventually remarried, but Marie never had any more children.

Hazel died in 1989 at age 75. Marie died in 1976 at 82. She never quite got over losing “her Greg,” Sharon said. “He was the big love of her life.”

SORROW TURNED TO PRIDE

On the Nevada side of Black Canyon, near Oskar J.W. Hansen’s famous Winged Figures of the Republic, another sculpture depicts a man waist deep in water with his arms stretched toward the heavens. Hansen created it as a tribute to those who went to work on the dam and never came home — a number that reached 213, including those who died of natural causes and in nonconstruction-related ways. The inscription reads: “They died to make the desert bloom.”

The official death toll from construction accidents at the site was 96, but the real number was undoubtedly higher, said McBride, author of several books on Hoover Dam and Boulder City.

Accidents went unreported. Injured workers who died at hospitals or at home were not classified as workplace fatalities.

“Basically they didn’t count you as dying unless you were killed on the spot,” McBride said. “There is no dependable number. There just isn’t.”

History does record this much: The Tierney men’s deaths book-ended a project that calmed a notoriously volatile river and helped give rise to the modern Southwest.

With Hoover as its linchpin, the Colorado now supplies water and power to some 30 million people and irrigates $1.5 billion a year in crops. The Las Vegas Valley draws 90 percent of its drinking water from the reservoir behind the dam.

“I’m proud, still proud of the work my family did on the Hoover Dam,” Sharon Tierney said. “Although some people see it as a big tragedy, I’m very proud of that connection.”

McBride said he doesn’t know of another historical coincidence quite like the one that afflicted the Tierney family. All you can do is marvel at it, he said.

“The myths you can explain. (They) usually have some basis in fact,” McBride said. “Here is a fact that has no explanation. The thing that cannot be explained is the very thing that happened.”

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Follow @RefriedBrean on Twitter.