Ex-FBI agent on Las Vegas 9/11 probe: Most ‘critical questions’ were answered

First in an occasional series on the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and their effect on Las Vegas.

On the morning that changed our nation, Grant Ashley was getting ready to fly to San Francisco for a work meeting when his brother called with the news.

Hijacked planes had crashed into the World Trade Center, eventually reducing the twin towers in lower Manhattan to nothing. And then into the Pentagon. And then into a field in Pennsylvania.

Nearly 3,000 people were dead and thousands more injured.

This has gotta be the work of Bin Laden, thought Ashley, the special agent in charge of the Las Vegas FBI field office at the time.

Ashley soon received haunting intel from his Washington, D.C., colleagues: Some of the 19 hijackers had traveled to Las Vegas before carrying out the attacks.

“You’re going to have a lot of work to do,” he was told.

Within hours, the largest, most intense investigation of Ashley’s nearly three-decade federal law enforcement career would unfold at a stunning speed, stretching through the aching months ahead.

“It’s very painful to know that on multiple visits, they were staying so close to my office, within a thousand yards,” said Ashley, who retired from the FBI in 2006. “From a personal standpoint, if there was only some way that we could have known.”

The sorrow and anger that filled Ashley needed somewhere to go. He buried his head in the investigation.

To mark the 20th anniversary of the deadliest terrorist attack on American soil, Ashley, now 65, reflected in an interview with the Las Vegas Review-Journal on the probe — and its emotional toll.

“This is an interesting walk down memory lane that I think I denied myself for a long time,” the retired agent said in late June. “Nobody ever asked me what it all meant to me. I’ve always looked at it from the other side, the law enforcement side, but of course, it touched me personally.”

Two decades ago, with the pressure of the massive investigation mounting, Ashley quietly worried about his wife, Linda, a flight attendant for United Airlines.

Airplanes held a special meaning in their relationship. They had met on one.

On a flight home from Quantico, Virginia, Ashley was assigned to a middle seat — sandwiched between his future wife and her brother.

“It was the best middle seat I’ve ever had,” Ashley has said.

Now, the very thing that had brought them together had been turned into a weapon.

On the morning of the attacks, the couple watched as the unimaginable unfolded on their boxy television set.

“That’s one of mine,” his wife had said as they watched United Flight 175, a jetliner stamped with a big “U” on the tail, smash into the South Tower of the World Trade Center.

The next day, Ashley again watched the unimaginable unfold inside his home as his wife put on her work uniform.

Concerned and exhausted, Ashley asked, “Where are you going? What are you doing?”

“That son of a b——- got one day,” she said, referring to al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden. “But not today. I’m going back.”

He tried to level with her: “We don’t even know if it’s safe yet.”

She went to work.

So did he.

Meanwhile, the FBI had quickly obtained the flight manifests of the hijacked planes. The terrorists bought their seats on the flights with their “true names,” Ashley said, jump-starting the multi-agency investigation in Las Vegas.

“You wouldn’t believe how quickly this came together,” he said. “We had Southern Nevada’s public safety leaders assembled in one of my conference rooms within three hours. The beauty of it was that everybody wanted to be a part of the solution. No one cared whether you were a patrol officer, an intelligence agent, firefighter. It didn’t matter.”

Over the next few weeks, the FBI and local police worked around the clock to retrace the hijackers’ movements.

According to Terry Hulse, Ashley’s assistant special agent in charge at the time, one of their first major breakthroughs in the case materialized on a warm September night.

“We went to every single hotel,” Hulse recalled ahead of the 20th anniversary. “We just swarmed the area — Las Vegas, Henderson, North Las Vegas — literally at night.”

A low-budget motel on the Strip, nestled beneath the looming shadow of the Stratosphere, held a critical piece of the puzzle on a “three-by-five card,” Hulse told the Review-Journal.

According to motel records, the leader of the 9/11 mission, Mohamed Atta, had stayed at the Econo Lodge on multiple occasions, including on June 29, when he reserved Room 122 for two nights. He was driving a 2001 Chevy Malibu that time, with Nebraska license plate 743MPR.

Today, the property, at 1150 Las Vegas Blvd. South, is operated by SHARE Village Las Vegas, a nonprofit providing affordable housing to military veterans.

“So that was the start, and we just sort of went from there,” said Hulse, now 72. He retired from the FBI a year after the attacks, following 33 years in law enforcement.

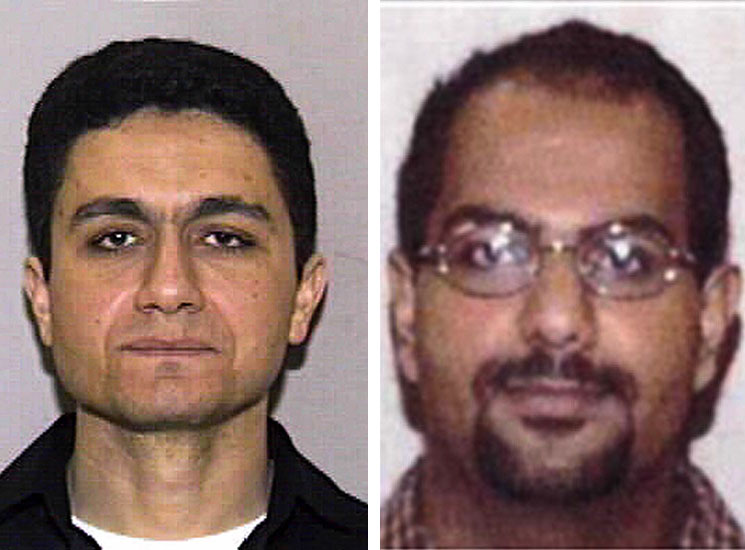

The investigation would reveal that at least one hijacker on each of the four hijacked planes — Atta, Hani Hanjour, Marwan al-Shehhi and Ziad Samir Jarrah — had visited Las Vegas between May and August 2001.

From left to right, Mohamed Atta, leader of the 9/11 mission and hijacker of American Airlines Flight 11; Marwan Al-Shehhi, hijacker of United Air Lines Flight 175; Ziad Samir Jarrah, hijacker of United Air Lines Flight 93; and Hani Hanjour, hijacker of American Airlines Flight 77. (FBI photos)

“This travel consisted of an initial transcontinental trip from an east-coast city to a west-coast city,” according to a declassified intelligence report published in December 2002, “and a connection in that west-coast city to a Las Vegas-bound flight.”

Each time, they flew first class so they could closely observe the cockpit and the activities of the flight attendants. They booked flights on Boeing 757s and 767s, the same jetliners they would commandeer in the attacks.

Why did they choose Las Vegas?

The investigation concluded with no concrete answer, but in the years after the attacks, two prevailing theories emerged in investigative reports. One suggests that the al-Qaida terrorists came to Las Vegas to scout potential targets. The other assumes they were in Las Vegas planning the attacks.

Ashley believes it to be the latter.

After all, Ashley said, the investigation had found that Atta, who piloted American Airlines Flight 11 from Boston into the North Tower of the World Trade Center, spent hours in June and August at the now-closed Cyber Zone, an internet cafe near UNLV, “looking at flights to see which ones had very few people, so they wouldn’t have to fight passengers.”

“Most people wrongly thought you could hide in Las Vegas. Of course, they didn’t care about hiding forever because they knew they would be dead,” Ashley said. “But in 20 years, look, has anything of that scale happened in Las Vegas? You have to look at it from that perspective.”

He added: “We painted a good picture. There were a few unaccounted-for miles, but almost all the critical questions were answered.”

Six months after the attacks, and after helping lead the Las Vegas investigation, Ashley reported to the FBI’s headquarters in Washington, D.C., for the final transfer of his career.

He would retire four years later, in 2006, as the executive assistant director of the FBI’s Investigations Technology and Law Enforcement Services.

In all, Ashley spent just three years of his FBI career in Las Vegas. But when it was time to go, he didn’t want to leave.

Through the hijacker investigation, Ashley forged lasting friendships with men and women across several law enforcement agencies. Among them are Katherine Landreth, Nevada’s U.S. attorney at the time; the Clark County Fire Department’s Earl Greene; and Jerry Keller, the county sheriff at the time.

Efforts to reach Keller for this story were unsuccessful, but according to a short biography posted to the website of Keller Elementary School, named after Keller and his wife, his work on the investigation had a great impact on the trajectory of his career.

Shortly after the attacks, which he described as a “morality check,” Keller decided against running for re-election.

Instead, he focused his efforts on homeland security issues, “rekindling some of the Y2K preparedness between fire departments” and the Metropolitan Police Department. Keller eventually went on to serve as the vice chairman of the Nevada Homeland Security Commission.

Something shifted in Ashley after 9/11, too.

He still loved his job, of course. It had been Ashley’s dream to become an FBI agent since he was 6.

His family and friends used to tease him that his life “was all about the bureau.”

But the attacks woke him up.

“For me, it washed away that jadedness you need sometimes to get this job done,” Ashley said. “It helped realign a lot of my personal priorities.”

In Ashley’s line of work, he had learned to be a skeptic.

“You’re always looking for what doesn’t fit, what needs to be fixed,” he said. “You don’t always take the time to appreciate the good, to take a few breaths and remind yourself that our people are good.”

Twenty years later, Ashley, his wife and their circle of friends — a mix of law enforcement types and former airline industry workers — still think about the attacks. And often.

“The conversation tends to turn to 9/11,” Ashley said. “It has to.”

He paused for a moment.

“Because it changed our country, our world, our businesses, our relationships,” Ashley said.

Contact Rio Lacanlale at rlacanlale@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0381. Follow @riolacanlale on Twitter.