Document details costs of UNLV’s domed stadium plan

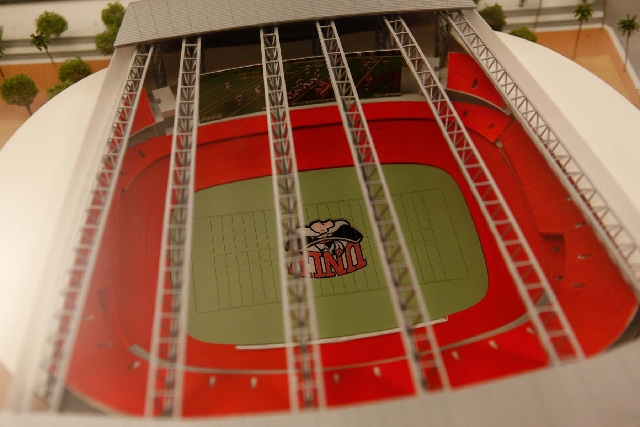

The estimated cost for UNLV’s proposed domed, 60,000-seat stadium is $548.4 million — the biggest chunk of the university’s $900 million stadium project, the Review-Journal has learned.

University officials have publicly refused to discuss project costs, but did share the price tag in a Nov. 20, 2102, cost estimate report with representatives of the hotel-casino industry and the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority who were invited to a private meeting late last year.

The newspaper obtained the information after filing a public records request with the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

The total Phase 1 project costs for what UNLV has dubbed the “Mega Events Center,” excluding financing costs, hit $899,841,523, according to the document prepared by Eiman Consulting. That includes $52.7 million in contingency costs.

The document represents the first look at the project’s cost estimate breakdown:

■ $158.9 million for parking improvements.

■ $40.4 million for design and consulting fees.

■ $40.4 million for “soft costs,” including insurance, bonding, taxes, legal and marketing fees.

■ $33.6 million for on-site improvements and utility work.

■ $20.4 million for new fields for softball, baseball, tennis, soccer, track/field and practice football.

■ $11.5 million for off-site improvements.

■ $9.9 million for replacement of campus service buildings.

■ $5.7 million for field and building relocation/facility replacement design fees, permits and utilities.

■ $2.7 million for a pedestrian bridge to span Swenson Avenue to athletic facilities.

While the proposed stadium has garnered the spotlight and scrutiny, the project has profound implications for other university sports. To build the stadium, which would be located not too far from the Thomas & Mack Center, UNLV will have to relocate the playing fields of several sports and build new facilities.

Those costs include $5.7 million for a new baseball stadium (originally proposed at $2 million in 1994); $3.8 million for a new tennis complex (pegged at $1.2 million in 1993); $3.4 million for a softball stadium; $2.7 million for a track and field facility; and $2.2 million for a soccer complex.

In addition, campus buildings will need to be relocated, including half a dozen buildings that will cost more than $950,000 apiece, according to the cost-estimate document.

The proposal pegged parking improvement costs at nearly $159 million, which would include money for new garages. After the price for the actual stadium, parking costs represent the project’s second-biggest dollar item.

Late last month, UNLV officials changed course on the stadium project, breaking off its partnership with private developer Majestic Realty in hopes of forging a closer bond with the Strip’s major hotel-casino companies. Majestic, owned by billionaire developer Ed Roski, who built the Staples Center in Los Angeles, had committed 40 percent of the UNLV project cost — or $360 million.

It’s unclear how UNLV will make up that contribution loss. University officials drew a cool response a few months ago when they privately floated the idea of the LVCVA and the resort industry contributing $125 million.

UNLV is also asking the Nevada Legislature to approve Assembly Bill 335, which would create a campus tax district and improvement authority to help generate income from taxes on the sales of food, drinks and other items at the stadium. But that tax would generate only $7 million to $8 million annually, said Craig Cavileer, who represented Majestic Realty.

The scope and costs of the $900 million project did not please some of the Strip’s big hotel-casino companies.

For example, MGM Resorts International in February said the stadium project “has grown too expensive for our community to support” and said it would support a stadium for UNLV “that is appropriately configured and responsibly financed.”

Don Snyder, UNLV’s point man for the project, said he expects the plan to be changed in response to cost concerns: “I cannot imagine NOT seeing some changes in the project and its costs as we go through the process of more fully engaging stakeholders.”

He stressed that UNLV’s focus “is on the enabling legislation which will provide a rationale framework to proceed with gaining stakeholder input and support for a facility which meets the needs of both UNLV and the resort industry.”

Assembly Bill 335 remains alive in Carson City.

Contact reporter Alan Snel at asnel@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5273.